I thank Neo Club Editions, Armando Anel and Idabell, his wife; Barcardi House of the University of Miami and the Institute of Cuban and Cuban-American Studies, and the Alexandria Library for the opportunity to present this excellent novel by Angel Santiesteban Prats, The Summer that God Slept, winner of the Franz Kafka literary prize, Novels Genre 2013.

I want to especially mention the writer Amir Valle who, at the time, called to my attention Santiesteban’s human and professional quality revealing to me an exceptional writer. Amir’s devotion to Santiesteban and his generous solidarity is good proof that communism has not been able to destroy the ties of friendship, although it has tried to control the emotional life of Cubans.

Repression as general punishment and intimidation

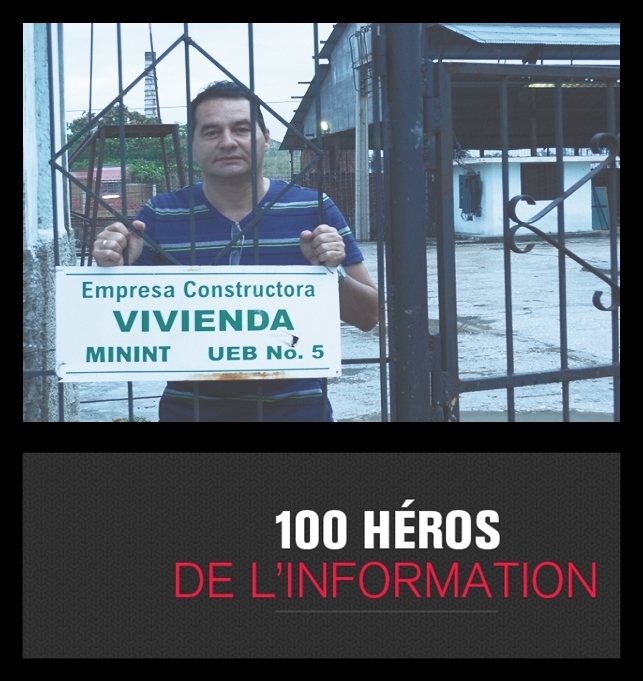

Santiesteban is a magnificent Cuban narrator, born in 1966. He was incarcerated by the dictatorship and condemned to five years in prison, supposedly for a crime of domestic violence that was never proved. In reality, what they punished were his criticisms of the system and his confrontation with the regime. The accusation was only the formal alibi to hide political repression.

Naturally, the Cuban regime hides its repressive hand behind the supposed independence of a judicial power that in Cuba is only another feared expression of the apparatus of terror.

If the Castro regime, really, felt that it should pursue those guilty of great atrocities, and if it did not use the tribunals selectively in order to harass its adversaries, it would have severely punished commander Universo Sanchez when he shot to death an inconvenient neighbor. Or it would have initiated a responsible investigation into the assassination of dozens of innocents on the tug boat March 13th. Or it would have delved seriously into the accusation made by Angel Carromero about the probable execution of Oswaldo Paya and Harold Cepero in July 2012, to mention only three cases among the hundreds of unpunished crimes and abuses that Cubans have had to endure.

I have seen, lived and suffered enough to know that the dictatorship invariably lies about the nature of its adversaries. It accuses them of being terrorists, CIA agents, alcoholics, traitors, or, as in this case, even of domestic violence, in order not to have to assume an unpleasant truth: they use defamation, acts of repudiation, beatings, jail and, sometimes, the firing squad, to reign in critical people who have the audacity of saying what they think.

At the same time, those maltreated by word or deed sow terror with the objective of making an example that will not be spread. It is preventive punishment. They strike so that others will lower their heads.

Repression in Cuba, well, it has two clear purposes that Lenin was already recommending at the beginning of the Bolshevik revolution: punish those guilty of deviating from the official line and intimidate the rest of the population. They are, of course, the same mafia methods converted into government measures.

That process of destruction of the reputation of the dissident or of the simply disaffected, especially if dealing with a famed intellectual, is always the prelude to jail or physical aggression. It begins with the insult and evolves into a savage kicking, ostensible and public, aimed at “giving him a lesson” so that he does not dare to contradict the sacred gospels of the tribe of thugs who occupy power.

Angel Santiestebal has gone through all this. They have beaten him, defamed him, they have tried futilely to silence him, but what they have managed is to convert his case into what is called “a cause celebre” that has awakened the attention of half the world.

Something similar to what, in the past, happened to Heberto Padilla, Jose Mario, Armando Valladares, Jorge Valls, Angel Cuadra, Reinaldo Arenas, Rene Ariza, Hector Santiago, Maria Elena Cruz Varela, Juan Manuel Cao, or Raul Rivero, and to so many other writers and artists who suffered various forms of the same ordeal.

The novel and the escape

The Summer That God Slept tells of the flight of a group of Cubans on board a raft. The narrator relates, almost always in the first person, the ups and downs of the trip, and describes the characters who accompany him from the time they embark on the Cuban coast, full of dreams, until they return to the island, on board a ship of the US Navy which takes them to the Guantanamo camps where an uncertain destiny awaits them.

In this case, the eventful journey is less important that the author’s disquisitions on Cuban history and the failed communist government. It is interesting to note a frequent presence in the novelist’s reflections: Jose Marti. Santiesteban, like so many Cubans, rightly, venerates Marti and uses his life and work as ideal and measure by which to judge what is happening on the Island.

The story is strong and dramatic for two reasons. The first, because thousands of Cubans have died of drowning or being devoured by sharks and barracudas in the seas near Cuba trying to escape from the communist system. That is to say, Santiesteban, in his fiction, which has so much of reality, gives a powerful voice to those thousand of victims. His novel, although the author has not proposed it, has a very important historical component.

How many Cubans have died in the attempt? They are dozens of thousands. It is not known exactly, but they are many. Some speak of 75,000, others double that. Without doubt, many more than those who have died in combat in all the wars fought on the Island since Colombus set foot at the end of the 15th century. And if they are not more, it is because Jose Basulto conceived and put in the air Brothers to the Rescue in order to help the rafters, until the dictatorship destroyed two of the unarmed airplanes that flew above international waters, killing four people who were just trying to help their fellow countrymen in danger of death.

The second reason that this novel is of notable importance is the theme of the relentless exodus of Cubans. Why or rather from what do they flee, if since the 18th, 19th and very particularly the 20th centuries, until the triumph of the Cuban revolution in 1959, the Island had been a net receiver of hundreds of thousand of immigrants, to the point of being the American nation that received the most foreigners in relation to its population? (More, proportionally, than Argentina and the United States).

They flee the lack of freedom, translated into lack of opportunity. Successive generations of Cuban residents always perceived the promising experience of living better than their parents and grandparents, something that they routinely achieved.

Until the Comandantes arrived, mandated that the dreams of prosperity stop and imposed on Cubans a system of government that impedes the creation of wealth, is incapable of maintaining infrastructure, and destroys accumulated fiscal capital, as is observed in those cities devastated by the unmitigated stupidity of Castro-ism.

When you are born in Cuba, you know that, as much as you may study or try, you will not be able to improve your quality of life because the system prevents it. That is why Cuba is the only country in the world from which engineers, doctors, writers and all those who yearn to do something constructive with their lives and undertake a lucrative activity to achieve their own well being and that of their families escape on rafts, risking death.

They flee also the lying and tiresome discourse that tries to justify more than half a century of social failures with heroic references to violent activities that lost all connection with the young generation.

What the hell does the remote battle of Uvero — a shootout elevated to the category of epic combat — or Che’s disastrous adventure in Bolivia mean for some young kids who want to have fun and normal lives that permit them to spread their wings and pursue their individual dreams?

And when they achieve it, when finally, they have managed to emigrate, they experience another facet of the horror: The State, that rancorous communist dictatorship bent on harming those who have fled and harassing and mortifying those who have stayed, denies them access to the academic titles that they legitimately acquired, sells them documents at exorbitant prices, describes them as scum or worms, treats them as enemies, and intends that the host country keep them in a legal limbo so that they cannot make their way.

While the rest of the nations of Latin America ask the United States to protect their undocumented citizens with such legal measures as the Law of Adjustment that protects Cubans when they touch US soil, the miserable State forged by the Castros tries to repeal such legislation. Not satisfied with the damage inflicted on Cubans when they live on the Island, it tries to prolong their suffering in exile, creating for them difficulties so that they cannot adequately develop.

Nothing of what is said here is different from what is quietly muttered by Cuban intellectuals who have not been able to or desired to seek exile, including many of those miserable ones who sign letters in UNEAC to support the tyranny or to applaud executions, pressured by the political police.

That’s why a voice like that of Angel Santiesteban Prats is so uncomfortable. Each time that a writer on the Island — and I think of Padilla, Maria Elena Cruz Varela, Antonio Jose Ponte, Raul Rivero, Yoani Sanchez, Ivan Garcia, and so many others — dares to describe reality without fear or swallowing the fear, their cowardly colleagues are victims of the disagreeable phenomenon of moral dissonance. They think one thing but say another, while they applaud what, really, deep in their hearts, repels them. The regime has managed to domesticate them, they know it, and they live with that annoying imprint that shackles always leave.

In the end, it must be very sad to live always masked officiating in the temple of the double standard. Angel Santiesteban Prats freed himself from that ignominy and wrote, in order to test it, a splendid book. Someday God will awaken, and he will come out of his cell. Thousands of readers await him thankful to give him the embrace that he deserves.

Published in NeoClubPress.

Translated by mlk.

4 June 2014