As my regular readers know, as a rule I don’t participate directly in the comments; my poor access to the Internet doesn’t allow me that interactivity. I prefer to return to the debates posted, after carefully reading every comment off-line, using the method of public rejoinder if it seems to be necessary to clarify certain aspects that shouldn’t be left without a response in order to avoid future misunderstandings.

In past days I allowed myself to comment on an article by an opponent of the regime, Darsi Ferrer, who, as is common when this topic is raised, has awakened in some readers certain considerations that would be useful to air here, in the space in which they were raise.

To do this, as usual, I will put my cards on the table. I have no intention of offending Darsi Ferrer; I use the virtual space rather than personal communications, in the same way he used it to publish his article where, among others, he mentioned my name, which calls even more for me to reply. In my capacity as a citizen journalist I allow myself the right to question any program, posture or opinion, come what may — be it the government’s the opposition’s, a national or foreign journalist or another blogger — with the same honesty with which I shine the public light on my own opinions with the intent to be questioned.

I do not understand how some consider this “an attack,” a “skirmish,” or something similar. That is, how long will we avoid transparency and debate for the sake of a poorly understood and worse interpreted “unity”? If an opponent, whomever it might be, feels it is damaging to have his views questioned, his leadership (if he has any), or his prestige, must be very fragile.

Are we proposing a perpetuation of the secrecy and conspiracies, in the image and likeness of the regime’s methods that so many of us reject so strongly? However, I know that the author of the article referenced has met occasionally with bloggers to whom I never stated such views, and I respect it: it was his choice.

The disagreements of some readers, however, don’t worry me — after all, we’re not a church choir — but some others display conceptual blunders that show how little idea they have about the nature of the Cuban alternative blogger phenomenon, for example, when they say that the mistake of the opponents is “not having been served by the blogosphere.”

I never tire of repeating that as a blogger I resist subordinating myself to anyone, that the essence of the blogger is total independence and I’m not a spokesperson for parties or individuals, making it impossible for them to “be served” by my journalistic activity.

I have no interest in “working in coordination”with any of the opposition groups I know, which has not caused the least offense to some friends who have spent years working within opposition groups.

On more than a few occasions I have submitted my opinions about some of their proposals, and, respectfully, I have expressed my views in private: I do not divulge political programs of any kind, nor do I sit down with anyone to develop a “common platform”; that is not my mission.

Oh! And do not be surprised if the day comes when this famous platform exists, and I also question it, as the free citizen that I am. On the other hand, I insist that nothing prevents opponents from opening their own blogs, as some already have done.

There are those who say that when I respond to what Darsi posed I am “diverting from the main objective” (I don’t know what this objective is; in fact, I am unaware that someone has attributed “objectives” to me that I myself have not enunciated). The same reader believes that if there are no objectives — I assume that he refers to the particular, supreme and sacred objective of “overthrowing the government” — then “I am writing just to write, as if freedom of expression was legitimate only when we criticize the Cuban dictatorship, and public opinion would have to have an orchestra in concert under the interests of the opposition.

I don’t feel myself authorized to speak on behalf of the blogosphere, given that we are not a homogeneous block, but as far as I’m concerned I don’t accept the simplicity encompassed in the hackneyed phrase, “They are fighting for the same thing.” It is a distorted view of reality. While the desire for a democratic Cuba is the shared dream of many Cubans, beyond those in the dissidence active in any denomination, we are not the same, we don’t project ourselves in the same way, we don’t “struggle” exactly “for the same thing.” And now I will say it again: Blessed be diversity!

Another reader rightly says that “everything is political.” I share that view, because each action by man in society in search of solutions is a political exercise. But it is one thing to have political opinions and something else very different to belong to a political organization. Especially in the case of Cuba, plagued by uncertainties and conflicts of every type of those who don’t escape some opposition groups; and where the lack of civic and political culture is a failing endemic to the social level.

In this particular, the blogosphere may, perhaps, be more related to the work of establishing bridges between different opinion groups and among the various sectors of society, than in political exercises itself with its corresponding ideological commitments.

Some bloggers, with our mistakes and successes, seek from the practice of virtual citizenship, to assist at the birth of true citizenship. It is a long-term effort, not an immediate one; it is a civic target, not an ideological one. A political group usually says: “think of me as a solution”; but an opinion blogger prefers to say, simply: “let’s think.”

As I see it, this can be useful to politicians if they are truly honest; because in the end, politics is a profession of SERVICE TO THE CITIZENRY, and thus the politician must be subordinated to it, and no vice versa. In this case, the citizen is me and the opponents are the politicians; where is the sacrilege?

There is no lack of paranoia about the ghost of State Security. The truth is that I care very little about what G-2 thinks about differences of opinion among dissident sectors. What’s more, that we publicly and respectfully disagree is a practice that greatly distances us from the frequent masked intrigues between people and groups of the nomenklatura, who are so accustomed to the State Security agents. What is their weakness can be our strength.

I love that in their “barracks” they are noticing the differences between their methods and ours. On the other hand, the supposed “gulf” between Darsi and I only exists in the minds of some readers with too much imagination. I wouldn’t hesitate for a moment to defend Darsi’s rights, like any other dissident or ordinary citizen; and I’m convinced he would do the same for me.

I think it is also important to clarify for the reader who says that virtual space allows those who write to hide their true identity. That’s true, but almost the all of the alternative Cuban bloggers use their own names.

Perhaps it’s surprising to know that some Cubans who have signed complaints about the opposition have refused to put their identity card numbers, much less to legitimize their signatures through a notary, as required by law to validate each document.

I know several of the signers of opposition projects who also signed, in 2002, to the irrevocable character of socialism in the Constitution of the Castros. This is not a criticism, they are both phenomena of countries ruled by dictators. I only mention it to point out that social dissimulation is not a characteristic inherent in virtual space, but in the entire Cuban society as a whole, a fruit of the despotic nature of this regime.

Nor do we write on the web to save ourselves from repression. The censors and their minions know who we are and where we live, ergo, we are as exposed as the opponents.

Finally, some reader referred to a phrase of Marti’s about the exercise of criticism which must happen “face to face,” The grave problem in decontextualizing Marti is that generally we forget that his Titanic political and patriotic labor — of astonishing force in many respects — took place in the 19th century. His principles are commendable and his example magnificent; but I am convinced that if Marti had had access to a tool as useful as the Internet, he would not have hesitated to use it as well to exercise his sharp (and often poignant) critiques.

That is the benefit of the technology is now within our grasp. So, my friends, forgive me if I suffer the mania of opinion; I have a critical eye and prefer to offer my points of view rather than remain silent. I don’t have the opportunity in life to go door-to-door telling each person what I think, so I have a blog. Don’t forget that in this case, neither did anyone knock on my door, nor was I the one who threw the first “stone.” I am in peace, there are no grievances.

April 11 2011

There is a question I’ve formulated on more than on occasion, and that I have recently revived. It goes more or less like this: “If I, who detests with every particle of my being the North Korean dynasty, for example, suddenly gathered my intentions and provoked an attack that killed dozens of North Korean civilians, would this effort be enough to call myself, from now on and proudly, an anti-Kim fighter?”

There is a question I’ve formulated on more than on occasion, and that I have recently revived. It goes more or less like this: “If I, who detests with every particle of my being the North Korean dynasty, for example, suddenly gathered my intentions and provoked an attack that killed dozens of North Korean civilians, would this effort be enough to call myself, from now on and proudly, an anti-Kim fighter?”

Translator’s note: The translation of this post was delayed; Voices 7 is now out.

Translator’s note: The translation of this post was delayed; Voices 7 is now out.

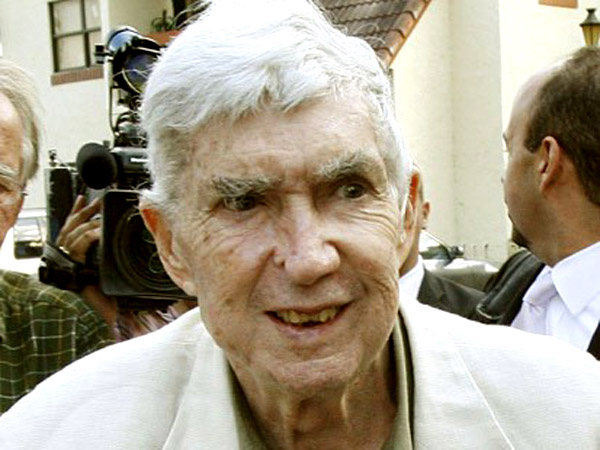

In a context of allegations in the media about an alleged war in cyberspace against Cuba, the former U.S. President Jimmy Carter has just arrived on the island invited by the Cuban Government. The significance of the visit is that Carter, during his presidency between 1977 and 1981, obtained significant results in foreign policy. Among them were treaties, including the Panama Canal treaty, the peace accords at Camp David between Egypt and Israel, and the SALT II treaty with the USSR, and the establishment of diplomatic relations with China and opening of the U.S. Interests Section in Cuba.

In a context of allegations in the media about an alleged war in cyberspace against Cuba, the former U.S. President Jimmy Carter has just arrived on the island invited by the Cuban Government. The significance of the visit is that Carter, during his presidency between 1977 and 1981, obtained significant results in foreign policy. Among them were treaties, including the Panama Canal treaty, the peace accords at Camp David between Egypt and Israel, and the SALT II treaty with the USSR, and the establishment of diplomatic relations with China and opening of the U.S. Interests Section in Cuba. In the early ’90s, the Reverend Rolf Rasmussen, minister of the Asane Church in Bergen, Norway, received an unexpected telephone call on Christmas eve. A mob of “Black Metal” music fanatics with clear satanic affiliations had set fire to his two-hundred year old church and reduced it to cinders and ashes.

In the early ’90s, the Reverend Rolf Rasmussen, minister of the Asane Church in Bergen, Norway, received an unexpected telephone call on Christmas eve. A mob of “Black Metal” music fanatics with clear satanic affiliations had set fire to his two-hundred year old church and reduced it to cinders and ashes.

Denying my Father a Visit

Denying my Father a Visit