![]() 14ymedio, Xavier Carbonell, Salamanca, 29 October 2023 — “When you see cartoons being burned, soak your constitution.” Enrique del Risco’s warning doesn’t stand up to scrutiny because of its lucidity, in the country of the hoax and the practical joke. It is sad that it arrives late, more than 65 years after – as Jorge Brioso observes in his prologue to Historia y masoquismo [History and Masochism] (Furtivas) – Fidel Castro’s recently released revolution censored a cartoonist for ridiculing the rebels of the Sierra Maestra.

14ymedio, Xavier Carbonell, Salamanca, 29 October 2023 — “When you see cartoons being burned, soak your constitution.” Enrique del Risco’s warning doesn’t stand up to scrutiny because of its lucidity, in the country of the hoax and the practical joke. It is sad that it arrives late, more than 65 years after – as Jorge Brioso observes in his prologue to Historia y masoquismo [History and Masochism] (Furtivas) – Fidel Castro’s recently released revolution censored a cartoonist for ridiculing the rebels of the Sierra Maestra.

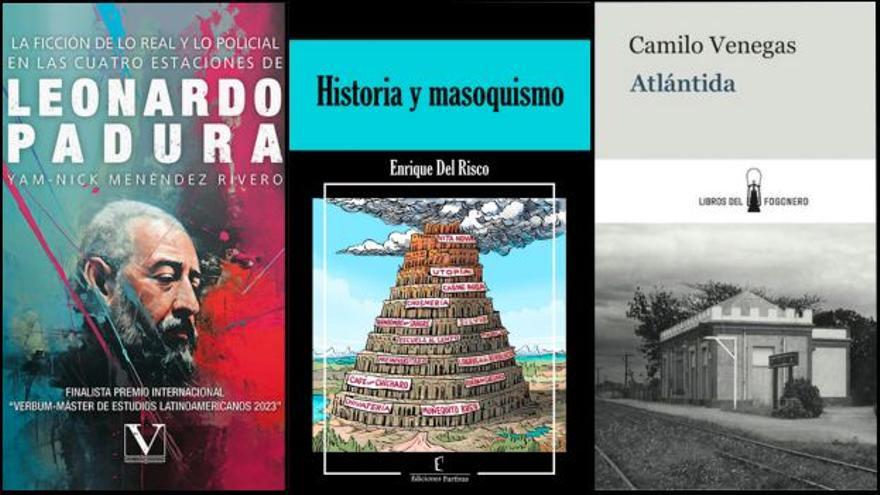

Del Risco’s most recent book puts his finger on the Cuban’s most painful wound: its tendency to suffer – with pleasure – chasing utopias. The fervor for the voice of the tyrant, the speed with which intolerance is assumed, submission, the ability to humiliate, the cult of vigilance… the dark side of the Island has been as present in its history as the tropical humor.

Perhaps, in fact, both are symptoms of a deeper character defect that the word “masochism” is just beginning to express. Well, “totalitarianism,” as Del Risco says, is “more than a political regime; it’s a culture, a civilization, a custom.”

El castigo [The Punishment] (InCubadora), the “monster book” by Jorge Luis Arcos that won the Franz Kafka Essay/Testimony Award, has also arrived in bookstores. Of the volume, which has the purpose of reflecting or (re)constructing” the Cuban canon, Carlos Aguilera has said that it is “full of anecdotes and sketches about Cuban intellectual life,” and that it “speaks loudly, but also in a whisper.”

Perhaps, in fact, both are symptoms of a deeper character defect that the word “masochism” is just beginning to express

InCubadora recently published a fragment of the book, which contains an exchange of letters between Arcos and Lorenzo García Vega about the events that motivated the end of the magazine Encuentro de la Cultura Cubana [Meeting of Cuban Culture], and the resignation for “ethical reasons” by several members of its editorial staff in 2009.

Las Cuatro Estaciones [The Four Seasons] by Leonardo Padura – the narrative tetralogy that inaugurates the adventures of detective Mario Conde – are studied in detail by Yam-Nick Menéndez in La ficción de lo real y lo policial [Reality and Police Fiction] (Verbum). The book applies several academic categories to the work of the Havana novelist and offers a conclusion: Conde’s stories are an underground, but not ineffective, manifestation of the tension between literature and totalitarianism.

En La Habana nunca hace frío [In Havana it is Never Cold] (Almuzara), by Zoé Valdés, takes place in the 70s on the Island. With a well-defined soundtrack – that of rock and the hippie movement – it narrates from nostalgia the lives of several young habaneros for whom freedom is a creed, and who face the intolerance of a puritanical and oppressive tyranny.

Atlántida [Atlantis] (Libros del fogonero), by the cienfueguero writer Camilo Venegas, refers to the same decade. The formula that guides the narrative also defines the country: “The struggle of the present against the past leaves many without a future.” For the author, a native of the Paradero de Camarones, the coastal town has its perfect metaphor in the ancient kingdom sunk in the sea.

‘Maine’ aims to fill an important gap: almost no historian has dealt with Masó, forgotten by all sides after the victory of 1898

Published by the exiled journalist Juan Manuel Cao, La gran locura [The Great Madness] (Universal) is a novel of “excesses, nonsense and lack of power.” Defined by its publisher as a grotesque story, with not a little of Cao’s life experience, its characters are “a tormented official, an eminent beauty, a delirious scientist and a boss with absolute power.”

Una historia develada [An Unveiled Story] (Universal), by José Ramón Fernández, who died in Coral Gables, Florida, in 2021, investigates the figure of Juan Masó Parra. The controversial mambí,* who left Havana five days before the blasting of the battleship Maine – which determined the entry of the United States into the war – after having proposed to the Spaniards to organize a Cuban brigade against the “invaders of the north.” The book aims to fill an important gap: almost no historian has dealt with Masó, forgotten by all sides after the victory of 1898.

On October 15, when publishers around the world paid tribute to Italo Calvino for his centenary, the cultural curators of the Island – where Calvino was born in 1923 – offered a forced “rehabilitation” to the writer. Funded by the Italian Embassy in Havana, which prepared an agenda for the anniversary, the trilogy Nuestros antepasados [Our Ancestors] will be the only book by Calvino to which Cubans have access. If true, unlike other occasions, copies will arrive at the bookstores.

*Translator’s note: The mambises were guerrillas who fought against Spain for Cuba’s independence in the Ten Years’ War (1868-1878) and the Cuban War of Independence (1895-1898).

Translated by Regina Anavy

____________

COLLABORATE WITH OUR WORK: The 14ymedio team is committed to practicing serious journalism that reflects Cuba’s reality in all its depth. Thank you for joining us on this long journey. We invite you to continue supporting us by becoming a member of 14ymedio now. Together we can continue transforming journalism in Cuba.