![]() 14ymedio, Xavier Carbonell, Salamanca, 15 October 2023 – No one would have guessed that publishing Italo Calvino in Cuba – where an ’absolute freeze’ on his books was declared in 1971 – was going to become a coin of diplomatic currency between Rome and Havana. Scholars and ambassadors, aficionados and bureaucrats, teachers, critics and drowsy leaders are getting together at the moment to celebrate the centenary of the writer – who perhaps would be amused to see just how elastic is memory for the censor, over there in the tropics.

14ymedio, Xavier Carbonell, Salamanca, 15 October 2023 – No one would have guessed that publishing Italo Calvino in Cuba – where an ’absolute freeze’ on his books was declared in 1971 – was going to become a coin of diplomatic currency between Rome and Havana. Scholars and ambassadors, aficionados and bureaucrats, teachers, critics and drowsy leaders are getting together at the moment to celebrate the centenary of the writer – who perhaps would be amused to see just how elastic is memory for the censor, over there in the tropics.

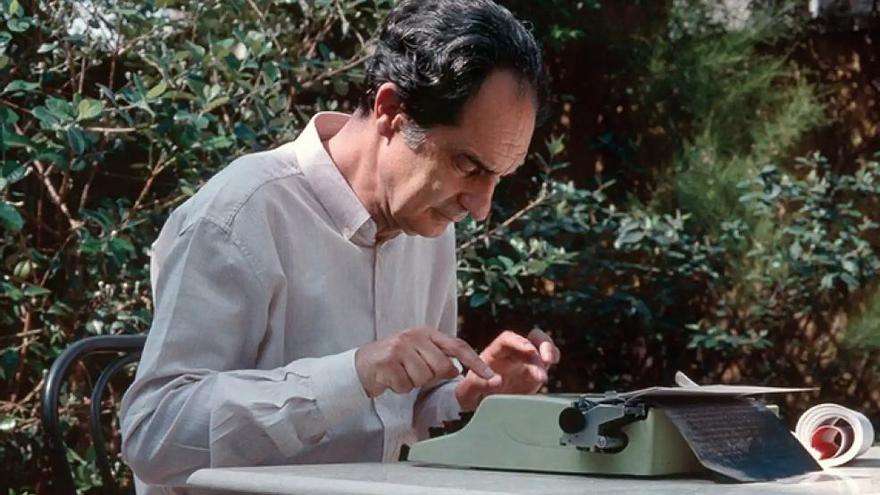

This ’witches coven’ is anything but harmless. Culture – or that which the regime thinks is culture, through much filtering and editing – is one of the ways it tries to convince Europe that some civility remains on the island, and that the Italian embassy’s money can be used to print books, although in microscopic print runs – books which were prohibited in earlier times. To rehabilitate the author, those who once buried him alive – for having defended Herberto Padilla after his arrest by State Security – are now insisting on his origins. Born in Santiago de las Vegas (Havana) in 1923 and married in Havana in 1964 to the Argentinian Esther Singer, Calvino couldn’t be anything else – they argue – than a lost Cuban destiny, or just an Italian by mistake.

Italo’s parents, Mario Calvino and Eva Mameli, moved to the island in 1917, during the period of the Mario García Menocal government. Their house – where their son was born – is today the headquarters of the Institute of Fundamental Investigation into Tropical Agriculture and it keeps a small, almost unspoilt, archive of the family, for the studious.

Occasionally Menocal and Mario Calvino exchanged letters: “This tree, which is in such poor condition and is little appreciated by those who wait for it to bear fruit – I’d like to see whether you can manage to help it get its vitality back and produce what the country rightly expects it to. Here, they give you a hatchet to do the job. Please know that you can do it properly. You have the chance to do something good for Cuba”. The tree – which appears to be a disagreeable metaphor for the country – was saved by the agricultural expert, not without complaining that “there were people who didn’t want it to prosper”.

An article published a few years ago in Opus Habana, the Historian’s Office magazine, praised Eva Mameli for a suspiciously patriotic gesture: swapping the old Cuban flag on the then Special Agronomic Station, where the couple lived, for a new one. Mameli gave birth to Italo in 1923 and two years later they returned to Sanremo in Liguria, Italy.

The very young age of Italo when the Calvinos returned to Italy contributed to how he was brought up as a European without any memory of being creole

The very young age of Italo when the Calvinos returned to Italy contributed to how he was brought up as a European without any memory of being creole. Calvino could only be Cuban by force – to use Cabrera Infante’s expression – which is bad news for Havana and its friends at the Italian Embassy.

Calvino visited Cuba in 1964; he went to see his parents’ old house, and he married Singer. The Mexican writer Jorge Ibargüengoita well remembers the dull soporific climate of Havana in his chronicle Revolution in the Garden. Calvino – who had awarded one of Ibargüengoita’s novels, as a juror at Casa de la Americas – and his wife and the other invitees had to support a dissertation by Lisandro Otero on Merendero of the Sharks, a corner of the Havana coast where the swimmers who dared to swim ended up devoured.

Four years later, thousands of copies of The Cloven Viscount – written by Calvino in 1952 – arrived in the Cuban bookshops, under the banner of Cocuyo, the same publisher as Salinger’s, Faulkner’s and other essential writers. The honeymoon didn’t last long: after Padilla’s detention the memory of the Ligurian born in the tropics fell into disgrace.

This Saturday an official journalist wrote that Cuba was a country from which Calvino “never severed his ties”. He wasn’t wrong: it wasn’t him, it was Cuba, its agents and its cultural investigators – the same ones who today award and publish him with the Italian Embassy’s money – who erased the author of Cosmicomics from their catalogue.

Now, the directors of the Writer’s Union are being photographed with the recently published trilogy, Our Ancestors. The fact that these three elegies to freedom, disention and criticism are being published on the island makes one sigh with relief: the censors will not be reading anything for a thousand years. Neither have the people who paid for these published copies – in a country with a context of absolute editorial debacle – told us whether they will be sold freely rather than to a select group of people – as has occurred with Calvino’s other titles.

Perhaps it’s only in this aching country where one can make sense of Marco Polo’s well-known saying to Kubla Khan in Invisible Cities: “in the middle of hell, it’s not hell” – and where this reading of Calvino is indeed for the Cubans.

Translated by Ricardo Recluso

____________

COLLABORATE WITH OUR WORK: The 14ymedio team is committed to practicing serious journalism that reflects Cuba’s reality in all its depth. Thank you for joining us on this long journey. We invite you to continue supporting us by becoming a member of 14ymedio now. Together we can continue transforming journalism in Cuba.