Benito is 85 years old. Every morning, outside a butcher shop in the Havana neighborhood of Vibora, he sits down with one of his ekobios (sect members) to chat about baseball, religion and politics.

He’s a tall black man, stern and full of infirmities. For 63 years he has been part of a abakuá sect called Enmaranñuao. He is the Plaza and Mokongo of his “game,” which means he is the person in charge of preserving and following the rituals and principles of the religion. As in any abakuá sect, only men are accepted.

“To be a worthy individual you don’t have to become abakuá, but to be abakuá, it’s essential to be an honest man. It’s the golden rule of the sect, whatever the label or ritual,” he says on a cold, gray afternoon while smoking a brand-name cigar.

The abakuá sect was born at the end of the 19th century in Havana. Its antecedents go back to secret societies in the Nigerian region of Calabar. There are 43 sects. Only in the capital and the province of Matanzas is the cult practiced.

Each sect has its seal, which is the representation or “game” of the cult. There are over 120 games. In the beginning, they were created by black African slaves or their descendants who had been freed beginning in 1886, when slavery was abolished in Cuba.

Later, things changed. At the beginning of the 20th century, the first abakuá society of white men was founded. Alberto Yarini, the famous Havana pimp from San Isidro, was white and a respected abakuá.

Yarini, a legend made into a film, was stabbed over an issue of women at the hands of a French pimp. Then, and in tune with the multicolor Cuban society, abakuá fanned out.

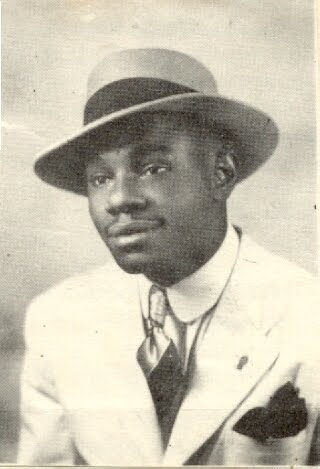

Although other sects sporadically accept white people, until 1959 its members were black and mestizos, simple people who worked as stevedores in the port of Havana or in other tough jobs. There were also abakuás among artists and musicians, like the percussionist Chano Pozo, who used to play abakuá and Yoruba rhythms. Chano was found dead on a street in New York in 1948.

Benito’s father was an important abakuá. He taught respect for others, family and women. “In these stormy times, part of the Secret Abakuá Society has been distorted.”

“Money is also an element of weight. Guys with a lot of money pay to enter a sect. In the underworld of Havana, to be abakuá has become synonymous with being tough. There are a legion of dangerous criminals who are abakuás. In my time this was not so.”

The old ñañigo, as a sect member is called, stretches on his oak stool and recalls the past. “Good conduct of the Society was the norm. Only if a crime was committed for reasons of honor would we accept people who had been in jail. This is a cult of values, virile, but not at war, nor does it conflict with respect for the law and for those who have any.”

Now everything is different, he says. “Even the prisons have sects. The temples seem to be public fiestas. Anyone can attend. It’s horrible. Guys who have stabbed an old lady, robbed a house or beaten women feel entitled to become abakuá.”

In the first years of revolution, the police looked at the abakuá sects with fear and respect. “It was their stumbling block. But the authorities did not try to obstruct our meetings. It’s been a distant but correct relationship,” adds this man with 63 years of belonging to an abakuá sect.

Other followers of Afro-Cuban religions agree with him. If honest, honorable men don’t try to turn things around, abakuá tradition, so deeply rooted in Cuban society, could become a racket for the worst kind of criminals. “In fact, it already is,” confesses Benito.

Photo: Chano Pozo

Translated by Regina Anavy

January 8 2011