![]() 14ymedio, Manuel Llorente, Madrid, 14 October 2022 — Federico García Lorca’s first adventure in the Americas could not have been more beneficial for him. The young man who, with a broken heart, embarked for the United States in 1929, bore no resemblance to the man who returned to Cádiz on 30 June 1930 aboard the steamer Manuel Arnús. While in the United States, he wrote A Poet in New York, a book which he handed over to José Bergamín shortly before he was assassinated in 1936, and which Bergamín published in 1940. With this collection, and in this collection, Federico extended himself further than in any other of his collected works.

14ymedio, Manuel Llorente, Madrid, 14 October 2022 — Federico García Lorca’s first adventure in the Americas could not have been more beneficial for him. The young man who, with a broken heart, embarked for the United States in 1929, bore no resemblance to the man who returned to Cádiz on 30 June 1930 aboard the steamer Manuel Arnús. While in the United States, he wrote A Poet in New York, a book which he handed over to José Bergamín shortly before he was assassinated in 1936, and which Bergamín published in 1940. With this collection, and in this collection, Federico extended himself further than in any other of his collected works.

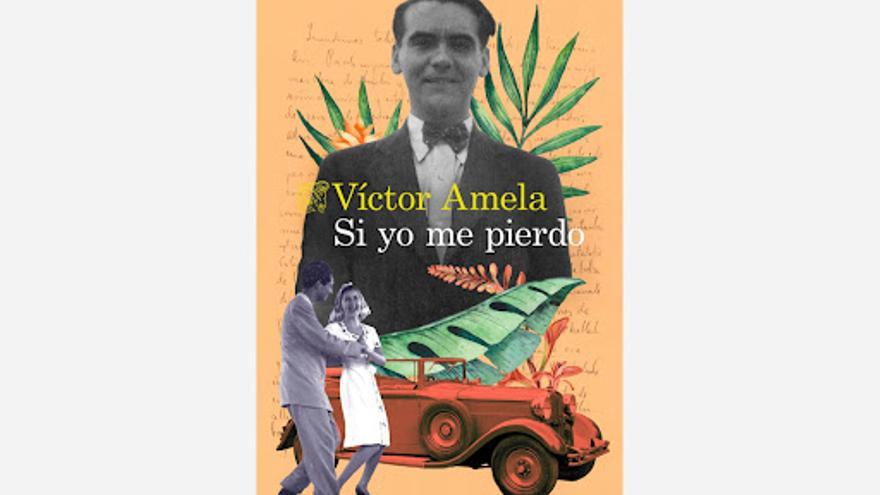

In New York he witnessed the stock market crash and was protected by friends, but it was in Cuba where he began to smile again. Lorca spent 98 wild and intense days on the island, a period which the writer and journalist Victor Amela unpacks in his novel If I Should Become Lost (Destino), a title which makes reference to a fragment in a letter from 1930 in which Lorca wrote: “This island is a paradise. Cuba. If I should become lost, look for me in Andalucía or in Cuba”.

Why write about these three months? “Because Federico García Lorca had confessed, upon leaving Cuba, that he had lived the best days of his life there. It had been from March to June of 1930. Lorca was dynamic, happy, in full enjoyment of his senses, and the sumptuousness of Cuba had afforded him every sensory pleasure: the negro son music, the rum, the ice cream and the Havana cocktails, the exuberance of the landscape and the beauty of the men and women of all skin colours. Behind the tragedy and sorrow of his murder, I wanted to get to know more about this tropical, party-animal Lorca. And then to tell his story”, Víctor Amela told La Lectura.

To begin with, Lorca had travelled to Cuba in order to give three lectures during the course of one week, but he ended up delivering nine in those 98 days, during which he also attended cult ceremonies, enjoyed himself by day and by night, and he wrote and sketched. “He frequented the roguish Teatro Alhambra, which encouraged him to complete El Público (The Audience) there — a homosexual drama in which he makes peace with his intimate self”. And La Leyenda del Tiempo (The Legend of Time) which Camarón de la Isla later made popular.

“Lorca lost himself in Cuba and then found himself again, discarding all the old worn out prejudices. He gave tribute to the talents of the island in his musical poem Son, written during a voyage of discovery by train, crossing the island by night from Havana to Santiago (’I shall go to Santiago’)”.

One particularly important poem in the Lorca canon – Ode to Walt Whitman – was also completed in Cuba, recalls Professor and Doctor of History of Art, José Luis Plaza Chillón, author of the recent study El Apocalipsis según Federico García Lorca. Los dibujos de Nueva York (The Apocalypse according to Federico García Lorca: The New York Sketches) (Comares).

A completely different man then, from the one who had arrived in New York in 1929 — a man who’d been abandoned by his lover, the sculptor Emilio Aladrén, who had preferred a woman to him, and who’d been “snubbed by his intimate friend Salvador Dalí, for having gone to Paris with Buñuel and for having criticised his Romancero Gitano (Gypsy Ballads). Lorca had sunk into a depression, and in order to distract him from his sorrows, and fearing he might commit suicide, his family had put him on a transatlantic voyage to New York, accompanied by Fernando de los Ríos as guardian”, claims Amela.

But what he finds there in that great American symbol of modern progress isn’t good. “New York greets the unhappy Lorca with the suicides that result from the crash of 1929 — such a terrifying sight. He is nauseated by the crudity of modern capitalism and the Anglo Saxon protestant coldness, and can only identify with the suffering he finds among the black people of Harlem, the children, and the poor”.

That journey is very important in the overall radical trajectory of his poetry. Ian Gibson, one of the greatest authorities on the poet of Granada, analyses it thus: “Before he goes to New York he’s already entering the orbit of surrealism, with pressure from Dalí and Buñuel in Paris. The screenplay he writes in New York as a response to Un Chien Andalou — titled Journey to the Moon — is clearly already surrealist. And the poems, often diatribes against the cruelty of the modern world, have an immense power. In these poems, apart from the odd exception, Spain hardly ever appears. As far as theatre is concerned, it seems that he began writing El Público — his most surrealist play — in New York, and it would be completed in Cuba”.

After 10 months in New York, on his way back to Spain he stopped off in Cuba, “where he gets back his beloved language, the sunshine and the colours, his Catholic virgins (combined with Yoruban/Nigerian saints), sensuality and beauty… In that sparkling Cuba, Federico felt more at home and back to his roots than he’d ever felt”, notes Amela.

Cuba, where he turned 32, entered into all of his pores, it saw him coming. Not only the climate and that outdoor life. With his gift for making friends he discovered well-known people like the Loynaz family who lived off the private income of their millionaire mother in the the finca ’Casa Encantada’, where they preferred to use carbide gas lamps over electric light. Enrique Loynaz used to sleep in a coffin, Dulce María (who was awarded the Cervantes Prize in 1992) besides being a lawyer collected teacups and teaspoons, Carlos Manuel would tie up one of the family dogs to the piano so that it would listen to his recital… And Flor, homosexual and poet, Federico’s favourite. He called her “my Cuban virgin”.

They both loved religious imagery, and together they would travel at high speed in an open-top Fiat 1930, driven by her, with Federico dressed in a 100% cotton drill white suit. Their relationship was so strong that the poet agreed to include various suggestions of hers in his play Yerma; he even ended up giving her the original manuscript as a present. Dulce María and Flor, with Fidel Castro in power, went on to draw a state pension. Flor ended up on her own, with a shotgun (for fear of being axed to death like her maternal grandparents) and 40 dogs.

“Lorca had many romantic flings in Cuba and he had great freedom to be who he was. There, he liberated himself from everything, it would seem. His lectures were an instant success and everyone wanted to have their photograph taken with him. There are thousands of anecdotes, many of which I heard myself sur place when I was there in 1986 preparing the second volume of my biography of the poet”, says Gibson.

Lorca even spent one night in a cell after a binge. He was rescued from there by Luis Cardoza y Aragón, a Guatemalan writer, who had been working for barely a few weeks at his country’s embassy in Havana, according to Víctor Amela. Lorca even had one or two moles operated on in the Fortún y Souza clinic in Havana.

In Cuba he met a young poet and student of law, José Lezama Lima, who also stretched language to its limits. Years later, that same author of the immense hieroglyphic that is Paradiso recalled of Lorca, that, after attending his last lecture in Havana: “His voice took on a deep intonation like that of a bell being struck by a finely-tuned clapper that all of a sudden stopped the excessive prolongation of the echoes”. Luis Cardoza was more direct: “His laughter was a naked girl”.

On the eighth of March 1930, the day after his arrival in the port of the Caribbean capital onboard the steamer Cuba, the poet wrote to his family: “My arrival in Havana has been quite an event, because these people are extravagant like no other. Havana is a marvel, both the old and the new. It’s like a mixture of Málaga and Cádiz, but much more cheerful and relaxed for its being in the tropics.

Weeks later he gave an account of a crocodile hunt. “I saw a fantastic number of crocodiles four or six metres long”; but he didn’t comment on the fact that he’d attended a demonstration against the installation of telephones, as the Cuban Telephone Company had installed fruit machine “one-armed bandits” with their shop-based apparatus, from which the business owners earned nothing.

Lorca’s stay in New York and Cuba was in reality an escape which José Luis Plaza Chillón compared to those of other exiles: André Gide in Tunisia, Jean Genet in Morocco, Pierre Loti in Turkey, E. M Forster in India, Henry de Montherlant in Spain. “The literature of the twentieth century written by homosexuals often presents the theme of exile, most commonly one which entails a personal banishment. Lorca, like other great artists exiled in modernity (Gauguin, Rimbaud, Kafka) becomes a prototypical creator for understanding part of the quest of the twentieth century”.

‘Son’ of the Cuban Negroes

When the full moon comes

I shall go to Santiago de Cuba

I’ll go to Santiago,

In a car of black water.

I’ll go to Santiago.

The palm roofs will sing.

I’ll go to Santiago.

When the palm wishes to be a stork,

I’ll go to Santiago.

And when the banana tree wishes to be a jellyfish,

I’ll go to Santiago.

I’ll go to Santiago

With the blonde head of Fonseca.

I’ll go to Santiago.

And with the pink of Romeo and Juliet

I’ll go to Santiago.

Oh Cuba! Oh rhythm of dry seed!

I’ll go to Santiago.

Oh warm waist and a drop of Madeira!

I’ll go to Santiago.

Harp of living trunks, croc, tobacco flower!

I’ll go to Santiago.

I always said I’d go to Santiago

In a car of black water.

I’ll go to Santiago.

A breeze, and alcohol in its wheels,

I’ll go to Santiago.

My chorus in the shadows,

I’ll go to Santiago.

The sea drowned in the sand,

I’ll go to Santiago.

White heat, dead fruit,

I’ll go to Santiago.

Oh bovine coolness of the reed grass!

Oh Cuba! Oh curve of sigh and mud!

I’ll go to Santiago.

_____________

Editor’s note: This article originally appeared on 10 October 2022 in the cultural supplement La Lectura of the Spanish national daily El Mundo. Reproduced here with permission.

Translated by Ricardo Recluso

____________

COLLABORATE WITH OUR WORK: The 14ymedio team is committed to practicing serious journalism that reflects Cuba’s reality in all its depth. Thank you for joining us on this long journey. We invite you to continue supporting us by becoming a member of 14ymedio now. Together we can continue transforming journalism in Cuba.