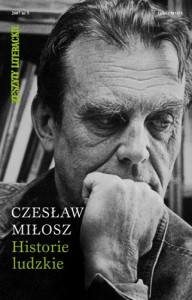

Among the writers neglected by Cuban publishers are famous novelists, poets and essayists of Eastern Europe who triumphed in Paris, London or New York, where they settled after bypassing the censorship and the subordination of the intellectual to power. Recently, we analyze the legacy of Romanian philosopher Emil Cioran, honored in 2011 for his centennial, as well as the Polish poet Czeslaw Milosz, Awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1980.

Among the writers neglected by Cuban publishers are famous novelists, poets and essayists of Eastern Europe who triumphed in Paris, London or New York, where they settled after bypassing the censorship and the subordination of the intellectual to power. Recently, we analyze the legacy of Romanian philosopher Emil Cioran, honored in 2011 for his centennial, as well as the Polish poet Czeslaw Milosz, Awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1980.

Milosz was evoked in the cities of Europe and North America through reprints, articles and conferences. Two of his books were published in Barcelona: His poetry anthology, The Unattainable Earth, selection and translation by Beata Rozga, and Milosz, selection, translation and foreword by Xavier Farre, from Gutenberg Galaxy / Circle of Readers, of 435 and 959 pages respectively.

Recalling the Polish Nobel ignored in Cuba, I found his resemblance to another poet and essayist, Adam Zagajewski (Lvov, Ukraine, 1945), who published To Sing and to Think, in El Pais of 1.10.2011, which recreates the life and work of Czeslaw Milosz, considered in Andrzej Franaszek’s biography as a contemporary encyclopedist, “complex, creative and very hard working, marked by the genius and work.”

Czeslaw Milosz did not avoid contact with contemporary thought nor with the ideologies the twentieth century was recorded. In his huge literary work he did not try for the absolute unity of poetic expression, but “advanced in different directions simultaneously, contradicted and argued with himself …”, although “at times he was of extreme simplicity, as if operating in two different creative processes: one oriented toward dialectical debate, controversy, protest and searching the web of ideas and postures; and another focused on pure lyricism.”

During World War II he remained in Poland and witnessed the massacres of the Nazis and the Stalinists. Despite his admiration for Marxism and his friendship with the revolutionaries, he considered futile the Warsaw Uprising in 1944 and the immolation of hundreds of youngsters before its occupants. “He shared the leftist sensibility, but ridiculed those poets who went to the over to the side of political propaganda. He was, from the time he was young, a wise and thoughtful individual, who was fascinated by thinkers and poets of extreme ideas. “

His lyrical work shifted from admiration for French poetry to Anglophone authors: William Blake, T.S. Eliot and W.H. Auden, which helps to understand the evolution of his apocalyptic waiting through the objective and intelligent record of the horror produced in the streets of Warsaw by the S.S. and the Gestapo. Rather than “metaphors of war, death, horror and hope, in his verses we feel the value of distance and reflection, expressed through irony and observation of events.”

He contrasted with the horror, the memory of a world of perfect goodness, as in the cycle titled The World (Naive Poem), and Campo dei Fiori and A Poor Christian Looks at the Ghetto, which exemplifies the humanism of poetry at cataclysmic times.

After the war he accepted the communist regime imposed by the Russians in Poland and worked as a diplomat for five years in the United States. But did he not compromise his verses with the fleeting loyalty of the functionary. He warned in his Moral Treaty that “The avalanche changes direction depending on what rocks it encounters in its path.”

After the war he accepted the communist regime imposed by the Russians in Poland and worked as a diplomat for five years in the United States. But did he not compromise his verses with the fleeting loyalty of the functionary. He warned in his Moral Treaty that “The avalanche changes direction depending on what rocks it encounters in its path.”

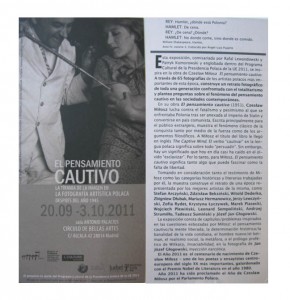

In 1951 he was granted asylum in Paris, becoming a political writer. In his essay The Captive Mind he analyzes the ideologies of the twentieth century and the mixture of seduction and persecution applied by the communists to the intellectuals.

Despite the success of his essay, Milosz felt reborn in poetry, for in his poems, written between Europe and California, USA, where he worked as a teacher of Polish literature at the University of California at Berkeley from 1966; he rediscovered images of childhood, Lithuanian nature and relaxation after academic disputes.

As noted by his compatriot Adam Zagajewski, on the awarding of the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1980, the Swedish Academy rescued Czeslaw Milosz from oblivion. Given the absence of his works in this Caribbean island, I present the reader with a piece of his beautiful poem Mittelbergheim:

I keep my eyes closed. Do not rush me,

You, fire, power, might, for it is too early.

I have lived through many years and, as in this half-dream,

I felt I was attaining the moving frontier

Beyond which color and sound come true

And the things of this earth are united.

November 8 2011