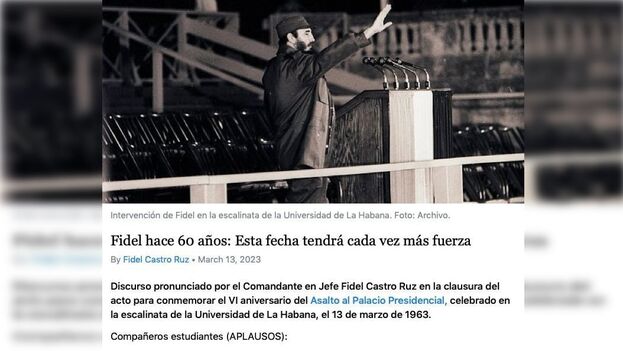

![]() 14ymedio, Xavier Carbonell, Salamanca, 14 March 2023–Universidad de la Habana, March 13, 1963. Fidel Castro leaned on the podium, at the top of the stairs facing thousands of students. Dressed in a suit, grimacing, are: President Dorticós; the adventurous geographer Antonio Núñez Jiménez; youth director José Rebellón; and the parents of Camilo Cienfuegos, who had died just a few years earlier. He gives a long speech. The next day, the press repeats the same headline, Castro promises a “firm hand” for the “weak,” the “lazy,” the “religious,” the “blue jeans,” the “lumpen,”and all kinds of “worms.”

14ymedio, Xavier Carbonell, Salamanca, 14 March 2023–Universidad de la Habana, March 13, 1963. Fidel Castro leaned on the podium, at the top of the stairs facing thousands of students. Dressed in a suit, grimacing, are: President Dorticós; the adventurous geographer Antonio Núñez Jiménez; youth director José Rebellón; and the parents of Camilo Cienfuegos, who had died just a few years earlier. He gives a long speech. The next day, the press repeats the same headline, Castro promises a “firm hand” for the “weak,” the “lazy,” the “religious,” the “blue jeans,” the “lumpen,”and all kinds of “worms.”

Sixty years later — this Monday — the regime’s press dusted off what was one of the most sinister speeches given by the caudillo after 1959. On Tuesday morning, the publication, shared as a special in Cubadebate, had been taken down without explanation. The speech, however, remains accessible at this link there is the cached version created by Google which Cubadebate cannot erase.

Attempts have been made to tone down or even justify the so-called “speech at the staircase,” which gave way to the creation of what were called Military Units of Support to Production (UMAP) and the persecution of homosexuals, members of several religions and “off-track” intellectuals.

Personalities like Mariela Castro Espín, the leader’s niece and founder of the National Center for Sex Education (Cenesex) have not viewed Castro’s assault on homosexuals favorably and try to attribute his intolerance to “the times” and not to a political strategy.

Why are they interested in rescuing the regime from an oratory piece which ends by requesting the assassination of Jehovah’s Witnesses and capital punishment for common delinquents? The answer, given the context of ideological radicalization pushed by the Communist Party nowadays, is unsettling.

Leafing through newspapers of that time or the popular Bohemia magazine allows us to take the pulse of that era. Military slogans, threats against any “Elvispreslian” attitude — one of Castro’s barbarisms that went down in history — interviews with leaders and news from the Soviet Union. Even the comics are eminently misogynous and sexual, to confirm the leader’s mandate: 1963 must be, even “by force,” the Year of Organization in all areas of life.

When Castro rose to the university podium, he was supposed to commemorate the sixth anniversary of José Antonio Echeverría’s death and the young men who took control of the Presidential Palace and the Radio Reloj station in 1957. After the failed assault against dictator Batista, the group was brutally assassinated.

However, the comandante dedicated a mention to Echeverría — a Catholic leader with a strong personality, whom Castro always viewed as a rival — to “apologize” for having allowed a group of radicals to erase from his statement “an invocation to God.” That act, he said was “erroneous and not revolutionary.”

Then, the “commemorative” speech took a spectacular turn and centered on the problems of the present. The recurring theme was Echeverría’s own religiosity: “Today, I will speak about others who, invoking God, want to make a counterrevolution.”

In a couple of phrases he neutralized the hierarchy of Catholic bishops who had published furious letters against the infiltration of Soviet communism on the Island. His government, he stated, “did not close churches, did not create obstacles for any priest willing to carry out his proper religious functions, and it could even be said that conflicts between the Revolution and the Catholic Church have begun to disappear.”

The waters have “leveled” with the bishops, Castro lied. His true objective was another, the Jehovah’s Witnesses, the Gideon Evangelicals, and the Pentecostal Church, three “Yankee sects” that had penetrated the Cuban countryside and that, to the chagrin of the military, proposed peaceful civil disobedience.

They drove him crazy, he admitted. “When it is time to harvest cotton, coffee, or sugar cane or when special work is required and the masses are mobilized on a Sunday, or Saturday, or any day, then they come and say, ’Do not work on the seventh day.’ And then they start with the religious pretext to preach against voluntary labor,” or they say, “Do not use weapons, do not defend yourself, do not be a militant.”

Castro accused them of being superstitious, of offending the homeland and the flag, and later asked what should be done with them for “preaching idiocies.” None of the young people hesitated, “Paredón!” — To the wall! That is the firing squad

It was just the beginning of the speech. The then Prime Minister continued talking about the ills they had inherited from the “capitalist past” and how they must draw a line between that and the present revolution.

Several “infectious focal points” remained, composed of “antisocials, thieves, pickpockets and parasites.” He stated that the police had been corrupted and the judges were soft in their sentencing. “The result: the need to take harsh measures,” he said, and asked the crowd what measures should be taken. Once again, drunk with enthusiasm, the university students responded, “Capital punishment!” and also, “Fidel, paredón for the thief!”

Satisfied, Castro increased the response. What can be done, then, with the young men who gather in the “pool halls” and other recreational establishments, “full of slackers and lumpen”? With the prostitutes, dedicated to the “repugnant profession”? And with the rest of the religious? He invited those who wished to leave to the United States to walk away. “What do they expect?” he asked and his audience broke out in laughter.

The “soft” who dare to complain, he dug in, “we understand they should undertake physical labor, which is the type most needed at the moment, and that they should go work in agriculture,” as a “little reinforcement, but not much!”

He then stated the most famous phrase from that speech, the one that would decide the fates of thousands of young people in the sixties and that today the official press repeats intentionally, about what he called a social “subproduct” of 15 or 16 years: “Many of those young slackers, children of the bourgeois, go around with their pants that are too tight; some of them with a guitar and their “Elvispreslian” attitudes, and they have taken their debauchery to extremes, wanting to organize their feminoid shows freely in public.”

With the spiel against those with “weak legs” and the “crooked trees” he abandoned the podium. He’d leave them, he said, with a big lesson, “All the worst comes together. Don’t ever forget that, don’t ever forget it.”

In 1965, the UMAP system was already operating in Camagüey. “We have made our calculations,” warned Castro about that measure and its impact on “the New Man” that the Revolution desired. Thanks to that speech of 60 years ago, notable cultural figures paraded through the UMAP, such as future cardinal Jaime Ortega, troubador Pablo Milanés, and author Reinaldo Arenas.

On December 31, 1963, Arenas — an aficionado of “the world of Havana show business” — hugged his lover, a young man named Miguel and wished him a Happy New Year despite the “sexual persecution.” Miguel returned the hug through tears and said, “It’s unbelievable that Fidel has already been in power for four years.”

“Wretched,” wrote Arenas as he recalled that hug. “I thought that was too much time. He ended up arrested and taken to one of the concentration camps. I never saw him again.”

Translated by: Silvia Suárez

__________________

COLLABORATE WITH OUR WORK: The 14ymedio team is committed to practicing serious journalism that reflects Cuba’s reality in all its depth. Thank you for joining us on this long journey. We invite you to continue supporting us by becoming a member of 14ymedio now. Together we can continue transforming journalism in Cuba.