![]() 14ymedio, Xavier Carbonell, Salamanca, 16 July 2022 — Ernesto Guevara’s incursion into Bolivia to organize a guerrilla is the only espionage story that Castroism tells children. The story has all the ingredients of a James Bond movie: a charismatic and cynical protagonist, false passports, codes and code words, disguises to mislead the enemy and, of course, a license to kill.

14ymedio, Xavier Carbonell, Salamanca, 16 July 2022 — Ernesto Guevara’s incursion into Bolivia to organize a guerrilla is the only espionage story that Castroism tells children. The story has all the ingredients of a James Bond movie: a charismatic and cynical protagonist, false passports, codes and code words, disguises to mislead the enemy and, of course, a license to kill.

Unfortunately for Guevara – who ended up dead, a trait that differentiates him from 007 and other agents – his adventure in Latin America also depended on the tension between the United States, the Soviet Union and the local communist parties which, aligned with the Kremlin, did not welcome with great enthusiasm the presence of a scolding and authoritarian Argentine, no matter how enlightened he thought he was.

Fidel Castro, the Richelieu of this fable, should be added to the equation; Fidel’s pro-Soviet moves showed Guevara that he had nothing left in Cuba.

A careful reading of these last days of Guevara is offered by the writer Alberto Muller in his book Why Did Fidel Abandon Che?, published this year by the publishers Betania (Madrid) and Universal (Miami).

According to Muller, the rupture between Guevara and Castro began with Guevara’s withering anti-Soviet speech in Algeria, during the Economic Seminar of Afro-Asian Solidarity in 1965. At that time, the Cuban Revolution had gone from the utopian hallucination of Fidel to an increasingly obvious guardianship of the Soviet Union. Guevara had already promoted the drastic executions of La Cabaña and failed in his management as a minister and president of the National Bank.

Between 1964 and 1965, at numerous international forums, he continually preached about the need for a revolutionary utopia. He traveled to the Congo, Guinea, Egypt, China, as well as Algeria, where he accused the Soviet Union of exploitation similar to that of the United States and of political pettiness with underdeveloped countries.

Upon his return to Havana, a harsh discussion took place between Guevara and Raúl Castro, in which the latter offended the guerrilla and accused him of being a Trotskyite, without Fidel defending him. After this dispute, Guevara discreetly breaks with the dome of power in Cuba.

Muller describes that the escape responded to a pattern of behavior in Guevara. Asthmatic since childhood, he had incorporated in his psychology the desire to move away from the suffocation of the center towards the periphery. Among the derivations of this escape is his constant abandonment of home and the family in search of adventure.

In 1965, Guevara had already disappeared from public life. He was in hiding in Prague after the failure of the guerrilla in the Congo, which Egyptian President Gamal Abder Nasser had mocked in a previous interview. The president had asked him if he believed himself to be Tarzan, because “a white man like him had no business” among the Congolese guerrillas, who smeared dawa magic ointment and got drunk with pombe to be invulnerable to bullets.

After the African failure, Guevara begins to plan his incursion into Latin America, with the aim of taking Argentina as a base for a continental revolution. However, Castro and Manuel Piñeiro Barbarroja –- the famous architect of Cuban State Security -– redirected him to Bolivia, a country that did not offer favorable conditions for the guerrilla focus that Guevara intended to organize.

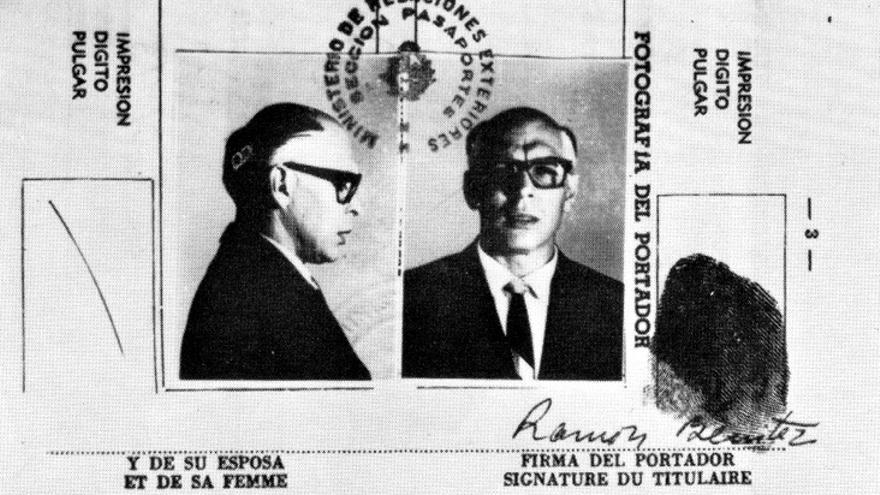

Disguised as a bald and myopic economist, Ernesto Guevara landed in La Paz on November 3, 1966.

Mario Monje, president of the Bolivian Communist Party, had held several meetings in Havana with Castro, Guevara and other officials in the first five years of the 1960s. In them he had argued that Bolivia would not respond to any revolution because the peasants owned their lands and the Party was against the armed struggle.

For this reason, Muller argues, the interference in Bolivia was a strategic suicide, since not even the communist cadres themselves supported the guerrillas. In a meeting with Monje in Ñancahuazú, the Bolivian leader leaves enraged by the guerrilla’s authoritarianism. Guevara, of course, interprets it as a betrayal of his movement.

Monje informs Fidel of the rupture –- which the American Central Intelligence Agency would also find out about -– but he never reveals the letter to the guerrillas, who are already going through their worst moments. Muller notes that, in the famous Diario del Che in Bolivia, Guevara writes feverishly, over and over again: “Total lack of contact with Manila.” Manila was the code name for Havana and Fidel Castro.

After an accusation, the guerrillas engage in combat with the Bolivian army in the Quebrada del Churo, on October 7, 1967. Guevara is captured by the military, who order his execution, despite the US request to keep him alive.

Guevara’s death was the result of what Muller calls “links of abandonment” between Fidel Castro and the Argentine. Because of his inflexibility and his criticism of the Soviet Union – Guevara preferred the alliance with China – he had become undesirable on both sides of the Iron Curtain.

The writer affirms that the abandonment was a tactical procedure that Castro carried out frequently. That is why his book includes a long and documented list of historical figures whom Fidel eliminated or dislodged – from Huber Matos to General Arnaldo Ochoa – considering them an obstacle.

“El Diario del Che en Bolivia,” according to Muller, “is the great prosecutor against Fidel Castro. There is no need for subterfuge or speculation or inventiveness. The document is available to everyone. Read it.”

Lastly, the book contains a collection of key files to understand the estrangement between Guevara and Castro, and how the latter turned the former, after his death, into one of the most invoked amulets by the international left.

The master move came from Castro himself, who built a mausoleum in Santa Clara in 1992 to house the supposed remains of the guerrilla and those of his fallen comrades. It was the definitive step to consolidate the romantic myth of Che Guevara and attract those nostalgic for communism to visit the Island.

_________________

The author of ¿Por qué Fidel abandonó al Che?, the journalist and professor Alberto Muller, was born in 1939 in Havana and spent 15 years imprisoned in Castro’s dungeons. Even today, an official encyclopedia defines him as a “terrorist.” When he met Jorge Luis Borges in 1983, in Caracas, and they talked about the Island, the Argentine writer pronounced the phrase with which Muller titled his memoirs: “Poor Cuba!”

¿Por qué Fidel abandonó al Che? Editorial Betania-Ediciones Universal, Madrid-Miami, 2022, 227 pages.

____________

COLLABORATE WITH OUR WORK: The 14ymedio team is committed to practicing serious journalism that reflects Cuba’s reality in all its depth. Thank you for joining us on this long journey. We invite you to continue supporting us by becoming a member of 14ymedio now. Together we can continue transforming journalism in Cuba.