The Cuban Foreign Ministry demands, in a strident tone, that the “majority support of the people” for Maduro be recognized

![]() 14ymedio, Rosa Pascual, Madrid, 1 August 2024 –On the third day, the United States changed its tone on Venezuela. The caution which the Secretary of State, Antony Blinken, expressed after the Venezuelan National Electoral Council (CNE) proclaimed the victory of Nicolás Maduro in the elections of Sunday, July 28, ended this Wednesday, when the White House woke up warning about being fed up waiting for the tally sheets of the vote after going to bed with the request to recognize the opposition’s victory.

14ymedio, Rosa Pascual, Madrid, 1 August 2024 –On the third day, the United States changed its tone on Venezuela. The caution which the Secretary of State, Antony Blinken, expressed after the Venezuelan National Electoral Council (CNE) proclaimed the victory of Nicolás Maduro in the elections of Sunday, July 28, ended this Wednesday, when the White House woke up warning about being fed up waiting for the tally sheets of the vote after going to bed with the request to recognize the opposition’s victory.

“Our patience and that of the international community is running out. We are tired of waiting for the Venezuelan electoral authorities to be honest and publish the complete and detailed data of this election so that everyone can see the results,” said White House National Security Council spokesman John Kirby at a morning press conference.

It was the preamble to the expression of some harsher words by Brian Nichols, in charge of the Department of State for Latin America, before the Permanent Council of the Organization of American States (OAS).

“With the irrefutable evidence based on the voting records, which everyone can see, it is clear [that the opposition] defeated Nicolás Maduro by millions of votes,” said the diplomat. The senior official referred to the electoral tally sheets published by the opposition in which it is observed that, with 81% of the documents provided, between Edmundo González Urrutia and Nicolás Maduro there are almost four million votes in favor of the first. continue reading

“With the irrefutable evidence based on the tally sheets, which everyone can see, it is clear [that the opposition] defeated Nicolás Maduro by millions of votes

“This is not a projection, even if Maduro wins 100% of the votes in the less than 20% of the votes that remain to be published, he could not surpass González,” stressed Nichols, who urged both the Chavista candidate and the other countries “of the world” to recognize the opponent’s victory. “Those who do not do it are allowing Maduro and his representatives to carry out an attempt at massive fraud and disregard for the order of the law,” he added.

However, the OAS, despite everything, did not reach an optimistic conclusion. The member countries did not have the necessary consensus to approve a resolution that asked the Venezuelan authorities to publish “immediately” the tally sheets of the elections. Although there was no vote against, the absence of Mexico and several Caribbean countries, added to the abstention of 11 countries, including Brazil, Colombia and Bolivia, led to the fact that the votes necessary to approve the document in an extraordinary session of the Permanent Council were not obtained.

The representatives of the member countries negotiated the document for more than five hours, but it was impossible to agree on a wording that everyone could accept. The resolution requested only that a “comprehensive verification” of the results be carried out “in the presence of independent observer organizations to guarantee the transparency, credibility and legitimacy of the results,” which had already been requested by “the relevant Venezuelan political actors.”

According to diplomatic sources, several countries that abstained asked to delete this last part, and others – such as Panama and Peru – opposed the deletion. Faced with that situation, unanimity was impossible.

Colombia’s abstention generated a wave of internal criticism from former Colombian presidents and politicians, who accused the Government of Gustavo Petro of being “an accomplice” of the “fraud,” which forced explanations from its foreign minister. Luis Ernesto Vargas pointed out that Venezuela has no representation in the OAS, so it would only be a “salute to the flag.” Bogotá, in addition, considers that the statements of the Secretary General, Luis Almagro, prevents the OAS from being an “impartial” organization.

This position is the same as that offered by Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador for not attending the meeting. Both countries are, along with Brazil, in dialogue with Chavismo “to create the necessary conditions and seek an agreement for coexistence and political peace,” according to the Foreign Minister. Other diplomatic sources say that the United States is working with these countries to find a negotiated way out for the regime. “This is the most important and difficult political operation of this century in America,” a participant in the talks told El País.

Colombia, Brazil and Mexico, along with the United States, are looking for a negotiated exit for the regime. “This is the most important and difficult political operation of this century in America,” say sources close to El País

This Wednesday, Argentina, Canada, Chile, Costa Rica, Ecuador, El Salvador, the United States, Guatemala, Guyana, Haiti, Jamaica, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, the Dominican Republic, Suriname and Uruguay voted in favor of the resolution. Antigua and Barbuda, the Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Granada, Honduras, Saint Kitts and Nevis, and Saint Lucia abstained. Dominica, Mexico, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, and Trinidad and Tobago did not participate in the session.

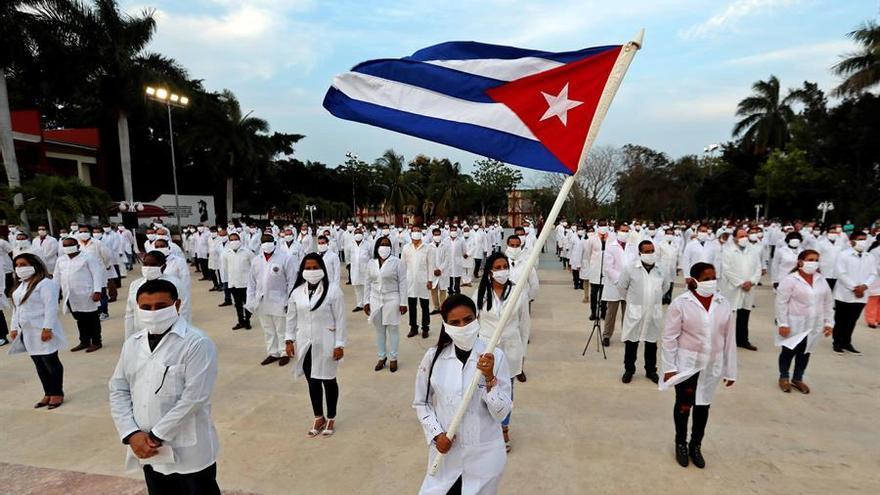

Cuba, which also does not belong to the OAS, made a public statement through its Ministry of Foreign Affairs in which it accuses the OAS of a lack of “moral or legal authority to resolve matters that only concern Venezuelans.” The text denounces the “long history of the OAS in the service of American imperialism,” its interference in the internal affairs of sovereign states and its support for “coups d’état, military dictatorships, repression and torture.”

The Cuban Foreign Ministry emphasizes that the “dignified attitude of a group of countries prevented the interference document from being approved,” but when mentioning that “the Venezuelan people decided to maintain their majority support for the option founded by Commander Hugo Chávez Frías” it ignores that it is left alone in closing ranks with a Chavismo that it desperately needs, if only for the oil.

The isolation is so great that Argentina also adhered to the almost universal position among the international left. The Union for the Argentine Homeland issued a statement in which it considered “the publication of the election tally sheets essential” and pointed to Maduro as responsible “for ensuring that the scrutiny is transparent with the corresponding counting of votes and display of the tally sheets before national and international observers.”

Also in Spain there was a movement of position by the left closest to Maduro, especially from the political parties Podemos and Izquierda Unida (IU), which went from demanding immediate recognition of the official results on Monday to adhering to the Colombian position and demanding “transparency in the results.”

“Let everything be done with transparency,” said the general secretary of Podemos who demanded the publication of “all the tally sheets,” but at the same time denounced the “Venezuelan right” for making an “openly pro-coup” speech. The federal coordinator of IU, Antonio Maíllo, valued the position of the president of Colombia as a “sensible” proposal. “It’s a good way without a doubt. From the standpoint of friendship of the peoples and looking at the common good.”

“It’s a good way without a doubt. From the standpoint of friendship of the peoples and looking at the common good,” said the coordinator of Izquierda Unida

The members of the G7 (four European countries, the United States, Canada and Japan) also urged Maduro yesterday to “publish the detailed electoral results with total transparency,” and expressed gratitude to González Urrutia, for “his solidarity with the people of Venezuela and his call for the publication of the detailed electoral results.”

“From all corners of the world, they support the legitimate demand of Venezuelans to respect their decision to change in peace,” added the Democratic United Platform (PUD), as well as calling for the protection of María Corina Machado, whom Maduro wants imprisoned.

“If you ask me my opinion as a citizen, I tell you that those people should be arrested, behind bars, and there has to be justice in Venezuela,” said the head of state at a press conference.

“They should, instead of hiding, appear before the Prosecutor’s Office and show their faces, instead of fleeing like cowards and continuing to incite their criminal groups to insurrection,” Maduro added, despite the fact that neither of the two opponents is in hiding anywhere, since this Tuesday they led massive demonstrations in Caracas.

The president also asked, before a gathering of supporters, that citizens denounce those who participate in the protests for “altering public order.” “We are going to open a special window of the VenApp page, which we use for the 1×10 of the Good Government, at page 58. It will be opened for the entire Venezuelan population so that they can confidentially put in the data of all the criminals who have threatened the people, who have attacked the people, to go for them, so that there is prompt justice.” Although a multitude of opponents claim to have managed to get Google and Apple to suspend the service, there is still no evidence that the option was enabled yesterday, despite the unverified videos circulating.

The president also asked, before a gathering of his supporters, for citizens to denounce those who participate in the protests for “altering public order”

The Government describes the demonstrators as “terrorists” and has already arrested more than 1,200 people, according to official figures. The Bolivarian National Guard (GNB) affirmed, without providing evidence, that those people were “trained for some time” in Peru and Chile, and also in “Texas” and “Colombia,”with the aim of going to Venezuela to “attack and burn, which is terrorism.”

In an effort to delegitimize those who denounce the fraud, Chavismo has been forced to open the political arc of the “fascist right,” in which it now includes the Argentine president, Javier Milei – who is accused of saying “stupidities” – and his Chilean counterpart, Gabriel Boric, who is considered left-leaning.

“We don’t care what you say,” said Diosdado Cabello, number two of Chavismo, in his TV program Con el mazo dando. On the program he spoke out mainly against Boric, whom he called “idiot,” “dummy,” “crooked” and”sellout,” as well as “very sad puppy of imperialism.”

Translated by Regina Anavy

____________

COLLABORATE WITH OUR WORK: The 14ymedio team is committed to practicing serious journalism that reflects Cuba’s reality in all its depth. Thank you for joining us on this long journey. We invite you to continue supporting us by becoming a member of 14ymedio now. Together we can continue transforming journalism in Cuba.