![]() 14ymedio, Rosa Pascual / Yaiza Santos, Madrid, September 22, 2020 — Cuban Prisoners Defenders (CPD) made public this Tuesday its complaint in front of the United Nations and the International Criminal Court (ICC), which it presented on August 24 in the names of 622 doctors from the Island who have been on missions abroad.

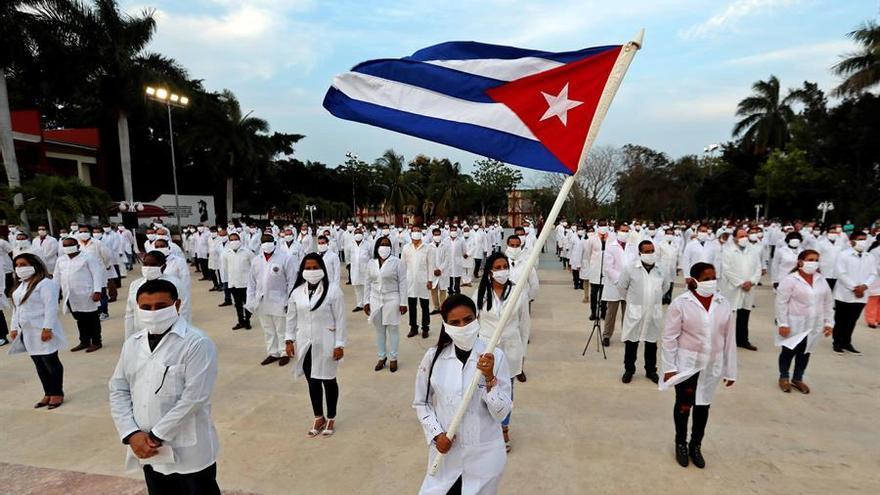

14ymedio, Rosa Pascual / Yaiza Santos, Madrid, September 22, 2020 — Cuban Prisoners Defenders (CPD) made public this Tuesday its complaint in front of the United Nations and the International Criminal Court (ICC), which it presented on August 24 in the names of 622 doctors from the Island who have been on missions abroad.

In May of 2019, CPD, headquartered in Madrid, announced the presentation of the first complaint, against six Cuban politicians including President Miguel Díaz-Canel and his predecessor, Raúl Castro. The document contained the testimonies of 110 doctors who denounced the conditions in which they were forced to work on international missions.

“We are denouncing situations of authentic slavery for hundreds of thousands of people. We believe that the prosecutor of the ICC could perfectly investigate those acts as crimes against humanity,” affirmed CPD member Spanish lawyer Blas Jesús Imbroda, at that time.

This Tuesday, in an online press conference, the president of CPD Javier Larrondo gave a hard recounting of the figures and data from the testimony of several hundred professionals included in the complaint, which he says has been very well received in international bodies.

According to the organization’s data, the missions usually last three years and between 50,000 and 100,000 professionals participate in them annually, 70% of them doctors, but also engineers, teachers, and athletes. Larrondo noted that the work of these professionals entails a profit for Cuba of $8.5 billion net ($6.4 billion in 2018, according to the most recent available official data). This is three times the profit that tourism reports, he detailed, while calling the missions “the great capitalist slave business of that country.”

The reports agree that the professionals are forced to participate in “conditions of slavery” with long workdays and restrictions on their freedom, such as, for example, being forbidden to drive a car or having to ask a supervisor’s permission to marry. The law, moreover, penalizes with from three to eight years in prison those who leave the missions, as written in article 135 of the Penal Code.

In most cases, the Cuban Governments takes away the professionals’ passports to retain them and pays them between 10% and 25% of the salary that it charges the receiving countries, under the argument that Havana needs money to finance the Health System.

Larrondo emphasized that these professionals are subject to Cuban law, and specifically Decree 306 of 2012, “On the treatment of the professionals and athletes who require authorization to travel abroad,” and Resolution 168 which, among other restrictions, includes returning to Cuba when the mission ends, informing the immediate superior “of romantic relationships with nationals or foreigners,” asking permission to travel to distant provinces or places, observing curfew from six in the evening, and asking permission to “arrange invitations to family members.”

“They have a special passport and it doesn’t work for customs. They can’t travel without authorization and never without the entire family.”

Nor are they allowed to take a copy of their university degree. “Without passport or degree, you aren’t a person,” said the president of CPD. “What does this sound like if not human trafficking and prostitution?” he stated.

Among the conditions that the healthcare workers suffer in these missions, the NGO included political work and obligatory proselytizing by the bosses, under the threat of being repudiated by their own colleagues.

Two of the doctors who are part of the complaint joined Larrondo. One of them, Manoreys Rojas, who now lives in the US and hasn’t seen his children in six years, told how when he left for the mission to Ecuador in July of 2014, he did it “to fulfill a program that he was not prepared for.”

He did it “because it was a way out economically, the only way to escape the country.” Rojas claims that the Cuban Government places its doctors in the worst parts of the cities, where they frequently suffer robberies, and that it forces them to do proselytizing work and to produce falsely inflated statistics. As for the objective of the missions, he is forceful: “pocketing money [by the government] at any cost and by any means possible.”

For example, medicines were sold by Cuba to Ecuador for $13.8 million, “medicines that they weren’t even able to use.”

Another doctor, Leonel Rodríguez Álvarez, had a similar experience. An internal medicine specialist, he was first in Guatemala and then in Ecuador, where he is now a university professor. Rodríguez related that Cuba sent Island nurses to Guatamala with a course of barely a few months in anesthesia and that they passed them off as specialized anesthetists, which caused conflicts with local doctors, who refused to work with them.

Also, he confirmed that State Security agents were sent to the missions passed off as healthcare workers. “Those of us who already had some experience, we realize when we are having an exchange with people who aren’t of our profession.” These people, specified Rodríguez, are also easily identified because they have a vigilant attitude, denouncing, for example, conflicting opinions. That the Cuba’s G2 security services intervenes in the missions, he asserts, “is an open secret.”

On that subject Larrondo gives as proof the case of Bolivia, where it was demonstrated that of the 702 members of the mission, only 205 were doctors.

The plaintiff organization argues that the ICC can hold accountable the 58 nations that have signed conventions against slavery.

This June, CPD directly accused Norway and Luxembourg of contributing to the financing of the system of slavery of Cuban doctors in Haiti and Cape Verde, and asked them to revise their triangular collaboration agreements to continue being an example in human rights for the entire world and to avoid facing a complaint before the Human Rights Court of the European Union.

The brigade in Haiti was established in 1999 and remains today, with almost 350 healthcare workers of whom the total number of qualified doctors is unknown. Norway, a country that doesn’t belong to the European Union (EU), although it does to the European Economic Area, has contributed a total of $2.5 million via three agreements of this triangular type since 2012 in the support of that mission.

The money provided by Oslo was mostly destined for the construction of permanent medical infrastructure, but a consignment of around $800,000 was planned for the Cubans who, in that country earn $250 per month, an amount lower than the already very poor salary of local doctors, who pocket some $400.

In the case of Luxembourg, which is a member of the EU, the cooperation dates back to this March, when it signed an agreement equipped for almost half a million Euros for the establishment of a contingent of Cuban doctors in Cape Verde.

According to CPD, the group established in that African archipelago is made up of 79 workers who provide support in different areas of health, as well as 33 members of the Henry Reeve brigade to combat COVID-19 financed by a tripartite accord with the European country.

In the specific case of the workers in Cape Verde, CPD cited an example of the vigilance to which they are subjected. According to a report, on August 7, 2017 a communication was sent between the office of then-Minister of Public Health, Roberto Morales, to the embassy in Madrid with a copy to the ambassador in Cape Verde in which was requested, by order of Colonel Jesús López-Gavilán, head of the Health department of the Ministry of the Interior, that an official from the diplomatic headquarters in Spain come to Adolfo Suárez Madrid-Barajas airport to supervise the layover that five doctors would have to make from Cape Verde.

The instruction was for them “to be investigated and check their communication with family members abroad” since, according to the sender, one of them had demonstrated “strong indications and intentions to ’desert.’”

Taking part in the press conference this Tuesday was Gilles Campedel, from the organization Prodie Santé, which has launched what it has called the International Brigade of Free Doctors. It is a project which, he said, is already present in 17 countries, and under whose protection Cuban doctors can work with just compensation – not less than 2,500 Euros per month, according to Campedel – and without intermediaries. “We have fantastic doctors and countries with the desire to receive them,” emphasized Campedel, who stressed that the pandemic is a good opportunity to get it off the ground.

The judge Edel González, ex-president of the Provincial Judicial Power of Villa Clara, seemed to agree that the brigades must “provide a service, but of quality, with transparency.” The objective of any analysis of the missions, he asserts, “is not to eliminate them but to humanize them.” After legally analyzing the complaint, he concludes that the punishments of the doctors who violate the law, like prohibiting them from reuniting with their families, is unconstitutional.

José Daniel Ferrer, president of the human rights organization Unpacu, expressed gratitude for the work of Prisoners Defenders in his case – the organization asked for his release on numerous occasions – and praised the creation of the brigade set up by Prodie Santé.

Ferrer, who noted that he has suffered a police cordon around his home for 74 days, addressed the politicians of other countries who participated in the press conference, including the Spaniard Javier Nart and the Argentinian representative Lucila Lehman, to ask them: “To what extent are the politicians and public opinion of your respective countries aware of the situation? What more can be done to show that the regime is neither in solidarity nor progressive?”

Translated by: Sheilagh Herrera

____________

COLLABORATE WITH OUR WORK: The 14ymedio team is committed to practicing serious journalism that reflects Cuba’s reality in all its depth. Thank you for joining us on this long journey. We invite you to continue supporting us by becoming a member of 14ymedio now. Together we can continue transforming journalism in Cuba.