![]() 14ymedio, Rosa Pascual, Madrid, 1 January 2024 — Lea Ypi has not written a book to make friends. Free [Libre], memoirs of the childhood and adolescence of an author who enters adulthood at the same time that her country, Albania, makes the leap to democracy, is a diptych as harsh with the lack of freedoms of the communism of her childhood as with the broken promises of a liberalism that tasted like disappointment. “In 1990 we had nothing but hope. In 1997 we lost that too.”

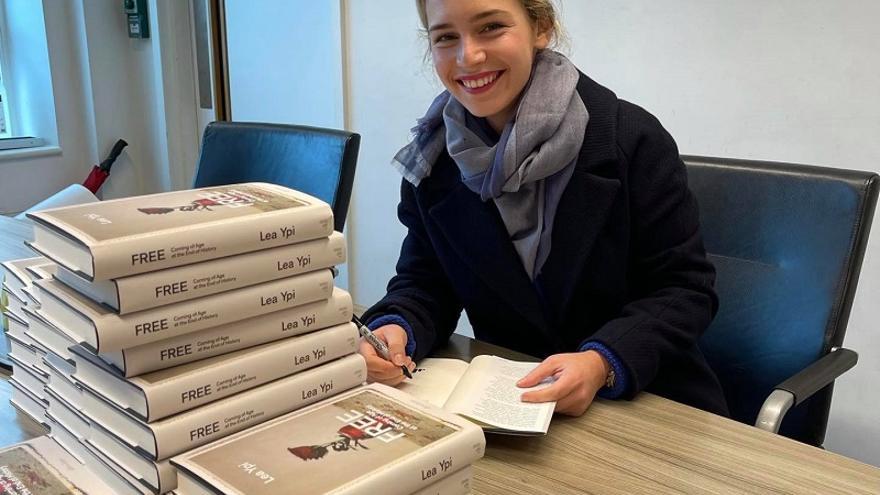

14ymedio, Rosa Pascual, Madrid, 1 January 2024 — Lea Ypi has not written a book to make friends. Free [Libre], memoirs of the childhood and adolescence of an author who enters adulthood at the same time that her country, Albania, makes the leap to democracy, is a diptych as harsh with the lack of freedoms of the communism of her childhood as with the broken promises of a liberalism that tasted like disappointment. “In 1990 we had nothing but hope. In 1997 we lost that too.”

“I never asked myself what freedom meant until the day I hugged Stalin.” With that powerful phrase, which was in all the drafts of the first (and, for now, only) novel by this Albanian born in 1979, the first part of the book unfolds with the subtitle The challenge of growing up at the end of history. The author, a political scientist at the London School of Economics, says that she sat down to write a philosophical essay about the overlap of the concept of the word freedom in communist and liberal societies, but “ideas ended up becoming people.”

Thanks to this turn, Ypi has created a novel that — better than any history book — relates the process of transition of her country from the dictatorship of Enver Hoxa to the rebellion that was about to lead to civil war. The lives – absolutely normal – of her characters, Lea’s family, friends and neighbors, paint a fresco of the daily life of communist society like no essay will.

The first ten chapters of the book are dedicated to this, with scenes in which readers who lived under the same system will soon recognize themselves.

The first ten chapters of the book are dedicated to this, with scenes in which readers who lived under the same system will soon recognize themselves. The lines to do the shopping, the start of classes shouting “pioneers of Enver,” the valuta stores for foreigners – where dreams come true – with their nylon stockings and Bic pens; the empty Coca-Cola can – a memorable chapter to which the book cover makes a nod – as a status symbol…

But, above all, the codes. Little Lea grows up hearing talk at home about how the biographies of her acquaintances had determined their studies, identified with an initial. Although, luckily, most ended up graduating, some ended up expelled. “I’m so sorry, it’s terrible,” is said in those cases. Starting in 1990, she discovered that the letter designated a prison, to be discharged was to be released and expulsion meant death.

Lea grows up in an apparently normal family, with civil servant parents moderately critical of the regime and an intriguing grandmother – the most interesting character in the novel and to whom it is dedicated – who, without being French, speaks French. The propaganda has taken strong root in her and she is, of all those who live in the house, the one who most fervently expresses her faith in the system, to the point of insisting, as her parents told her, that there were no photos of ‘Uncle Enver’ in their house because they were looking for a nice frame.

But at age eleven her life changes completely. “It was like the moment when they tell you that Santa Claus does not exist. We had built, for the children, a myth to explain the world. Now it was necessary to know the truth,” she has said in interviews.

Lea reaches adolescence and her world suddenly falls apart – “I was one person and then I became another.” Everyone she trusted had lied to her, everything she believed in was a lie. Her family history, her biography, had also determined her seemingly unremarkable existence, dating back to her great-grandfather (former Prime Minister Xhafer Ypi), whose last name was not, as she was led to believe, a coincidence; to her religion, Muslim, to the fact that she embraced it, along with her books, to find refuge in a dark adolescence.

That is the second part of the book, the one that will disappoint those who expected an ode to the benefits of liberalism and capitalism.

That is the second part of the book, which will disappoint those who were expecting an ode to the benefits of liberalism and capitalism and which rhymes with the author’s own disappointment.

“I had always thought that there was nothing better than communism. Every morning of my life I woke up wanting to do something to make it come more quickly. But in December 1990 the same people who had participated in the marches celebrating socialism and its advance towards communism took to the streets to demand its end,” she recalls in the novel.

Lea entered 1991 trying to join the democratic enthusiasm of her parents and trembled with the first free elections. She travels for the first time outside of Albania, to Greece where her grandmother Nini was born, and on the plane she sees something hitherto unheard of: “a colored plastic bag.” And she remembers perfectly the day when her mother brought home the first issue of the first opposition newspaper, whose motto was: The freedom of the individual guarantees the freedom of all.

But she soon discovers that when the words that the regime imposed on them disappeared – dictatorship, proletariat, bourgeoisie – only another omnipresent word remains: freedom. “It appeared in all the speeches on television, in all the slogans shouted angrily in the streets. When freedom finally arrived it was as if you were served frozen food: we chewed a little, swallowed quickly and were left hungry. Some asked if they had given us leftovers, others said they were just cold starters,” she writes.

Things happen before her eyes that she did not expect. Among them is the mass exodus of Albanians to Italy, repressed by the governments of both countries. “What value does the right to leave one country have if there is no right to enter another?” she asks, which in the case of many young women her age only served to cause them to be sexually exploited. Also the new business culture, which forces her father to order massive layoffs – “structural reforms” according to the new foreign businesspeople – or the great pyramid scheme that led the country to ruin and almost ended up unleashing a civil war.

But for teenage Lea, what hurts the most is the intimate thing, the conflict with parents who deny her the right to complain. “They had the feeling that they had always wanted this new world, but now they could no longer live it. It was my responsibility, they told me, to do everything that they could not do,” the author, explains, describing that stage of confusion, violence, insecurity, conflict and trauma that her parents previously disdained. “You’re not in prison, you’re not working in a mine, nor are they persecuting you. What are you complaining about?” they told her.

Ypi left Albania in the summer of 1997. She crossed the Adriatic and entered the Faculty of Philosophy and Literature at the Sapienza University in Rome. She had broken the promise she made to her father to distance herself from Marx – she is an expert in Marxism, among other things – and her CV is brilliant, but she lives with boredom having to explain in Western Europe the lack of freedoms of communism, and in Albania and other countries in the Soviet orbit the defects of a capitalism she believes “only emancipate a few.”

At university she made new friends who “declared themselves socialists” and spoke of Trotsky or Guevara “as if they were secular saints”

At university she made new friends who “declared themselves socialists” and spoke of Trotsky or Guevara “as if they were secular saints.” She was bothered when sharing her childhood stories with them and they, paternalistically, told her that this was not “true socialism (…)” without being able to hide their irritation. “The socialism of my university classmates was clear, bright and with a future. Mine was confusing, bloody and from the past.”

But she makes no concessions to his new reality. “Liberalism was synonymous with unfulfilled promises, with the destruction of solidarity, with the right to inherit privileges, with turning a blind eye to injustice,” she says.

Ypi believes that communism and liberalism have an overlap: “Both fail to understand the complexity with which ideas and history are mixed.” Her book has the potential to anger everyone, and yet, in such a polarized time, it has united critics and audiences in praise of it. And that is already good news.

____________

COLLABORATE WITH OUR WORK: The 14ymedio team is committed to practicing serious journalism that reflects Cuba’s reality in all its depth. Thank you for joining us on this long journey. We invite you to continue supporting us by becoming a member of 14ymedio now. Together we can continue transforming journalism in Cuba.