![]() 14ymedio, Manuel Pereira, Mexico, 15 April 2016 — In 1981 I was delivering some lectures about Cuban cinema at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) when I received a call in my hotel in the Zona Rosa neighborhood from Gabriel Garcia Marquez. He asked me to come to his house on Fuego Street in the exclusive Pedregal neighborhood. We ate at a nearby restaurant called El Perro Verde, or something like that. He asked me to read his latest novel, he was in a hurry, it was short.

14ymedio, Manuel Pereira, Mexico, 15 April 2016 — In 1981 I was delivering some lectures about Cuban cinema at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) when I received a call in my hotel in the Zona Rosa neighborhood from Gabriel Garcia Marquez. He asked me to come to his house on Fuego Street in the exclusive Pedregal neighborhood. We ate at a nearby restaurant called El Perro Verde, or something like that. He asked me to read his latest novel, he was in a hurry, it was short.

What was the mystery of such urgency? He knew that I was returning to Havana in a few days. “I can read it on the plane,” I told him. No, I had to do it in Mexico. He was in such a rush to give me the manuscript that he forgot his wallet on the table. He realized it when he got home and asked me to go look for it at El Perro Verde. The waiter was honest and had saved it, despite its being quite bulky, as I supposed the wallets of famous writers to be. “It’s all here,” sighed Gabo, after counting the bills. continue reading

He handed me the novel. I began to read it right away in his house, and then I locked myself in my hotel to keep reading. I read it in a couple of sittings, not knowing what the famous writer expected of me. The story of the two brothers who stabbed Santiago Nasar was well structured, flowed effectively, like everything from Gabo; with his impeccable craftsman’s prose, neither lacking or needing a single comma, the precise adjectives, the well-drawn characters. The following day we met again. Then he said to me, “You are the second reader of this work, after Mercedes of course.”

“It is an honor,” I replied.

But … what was the mystery of the hurry?

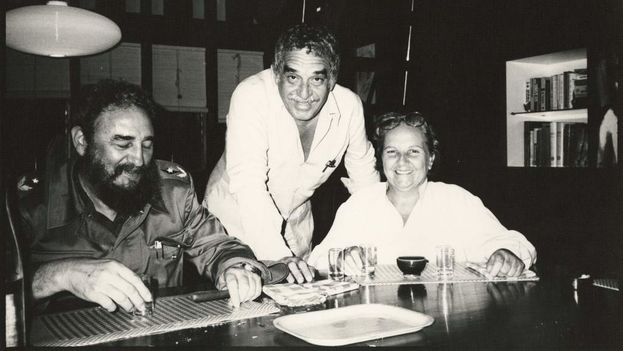

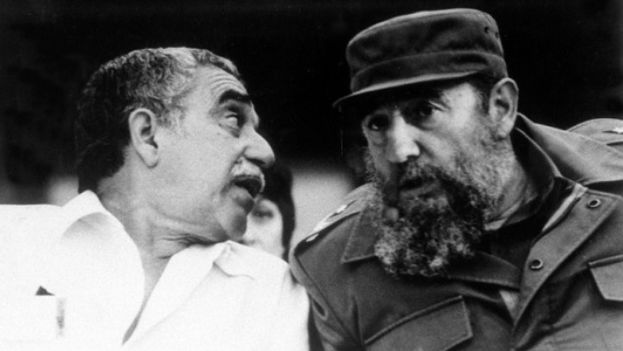

He confessed that he wanted Fidel to authorize him to publish this book.

Why?

Because he had made a public oath: he would not publish again while Pinochet remained in power. “And the problem is, he is not failing,” he grumbled. “And meanwhile, I wrote this book and I really want to publish it.” But before breaking his announced promise he should consult with Fidel.

Indeed, sinceThe Autumn of the Patriarch (1975) Gabo had not published any piece of fiction. Too long in silence for such an esteemed writer.

What did I have to do with all that?

“I want you to take this book to Fidel.”

“I do not personally know Fidel, I have no direct access.”

He hesitated a moment and added:

“But you know Carlos Rafael Rodriguez, right?”

“Yes, him I know.”

“Well, you give it to him to give it to Fidel.”

Then he wanted to know my opinion of the novel, which flattered the thirty-something I then was. With great tact I told him that his story reminded me of vaguely of Rashoman – the two stories from Akutagawa and Kurosawa’s film – because of its multiple witnesses and diverse versions of a crime, but he said no, his source of inspiration had been the assassination of Julius Caesar. I thought about the omens, the fatality of Greek tragedy, and concluded he was right, although the Japanese took nothing from Gabo, as was evident later with Memories of My Melancholy Whores, so akin to Kawabata’s House of the Sleeping Beauties, starting from the epigraph.

Twenty-four hours later I landed in Havana and handed the clandestine text (not foretold) to Carlos Rafael Rodriguez. Shortly afterwards Chronicle of a Death Foretold was published simultaneously in Colombia, Spain, Mexico and Argentina. Obviously, Gabo had obtained the imprimatur of Fidel Castro, as is proper of every high ecclesiastical or ideological authority. The Middle Ages in its purest state.