By Jeovany Jimenez Vega, M.D.

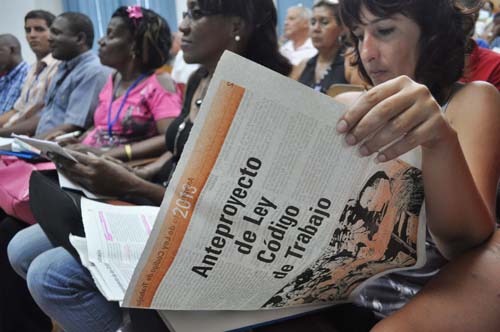

When I spoke during the discussion of the Draft Law to amend the Labor Code a couple of weeks ago, I said that our industry (public health) generates 50% of the GDP of this country; that it represents an income of between 8 and 10 billion hard-cash dollars every year; that this is a lot of money, which should be enough to significantly increase the salary of the sector that produces it; that those who remain here deserve as much as those who go on work medical missions abroad; that I will never understand why a prestigious professor of medicine, after decades of dedication, earns one-third the salary of an office manager trained for fifteen days.

It’s not just that our salary is ridiculous, but that it is particularly absurd in this country of merciless prices. We have patients who easily earn three to ten times our salary, and not from self-employment, but also from the few state jobs that link salary to performance; or simply through “struggling” — that is, stealing with both hands. It is high time to put an end to this humiliating situation, because if there exists today in Cuba a sector that is able to increase substantially the wages of its workers — here we’re not talking about the ridiculous two pesos per hour for nighttime work — it’s public health. I said all this, a couple of weeks ago, when I was able to speak.

My specific proposal? A basic monthly salary for a recent graduate of 800 Cuban pesos (roughly $33 US), increasing by 150 pesos every two years up to, for example, 1,500 pesos eight or ten years after graduation; 100 pesos per each medical shift at multi-specialty and primary care clinics, and between 150 and 200 pesos in hospice facilities depending on the workload assumed by each specialty, never less than 5 pesos an hour for night duty, 200 pesos for biohazard risk, 200 for administrative positions and teachers — it could be higher for provincial or ministerial positions; 250 for certified masters and 500 per specialty completed. And finally, it would be fair to give longevity pay after fifteen years of work at 100 pesos every five years (100 after the first 15 years, 200 after 20, 300 after 25 and so on) and finally a retirement that does not force those who served their people for decades to live on a little less than a beggar would get.

Of course, this is my humble opinion, launched into the ether from the perspective of the sufferer, not remotely like that of an experienced economist. But something convinces me that an industry generating so much money could handle it comfortably. They’ve already made a timid gesture with sports, so why not with the sector that generates similar wealth, which provides reasonable assurances that it will continue, and which is showcased to the world as a success story?

Those who make these decisions should take into account that these are professionals who know that, if they approved a monthly salary like this (I’m talking about 150 U.S. Dollars), it would still be less than they could earn abroad for a few hours of work under circumstances qualitatively very different, despite which — I venture to guarantee — in most cases they would not want to abandon their country. I remains to be seen if the words spoken in meetings all across this country will fall on deaf ears, if it will do any good to throw this bottle into the sea, to throw these crazy words into the wind.

Translated by Tomás A

17 October 2013