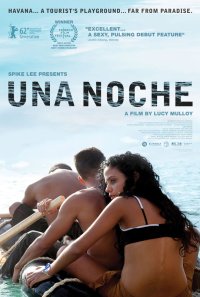

Because of the social theme it deals with, because of the magnificent photography of Trevor Forrest and Shlimo Godder, Roland Vajs’ and Alla Zaleski’s sound quality, and also director Lucy Mulloy’s script, the British-Cuban-North American co-production Una Noche constitutes an important cinematographic work, which, with its truthful narrative, gets close to documentary cinema; and, due to the authenticity of the people and social events it focuses on, it gets close to naturalism. Shot in Havana, with local actors, dealing with a national theme, the film can be considered to be part of the filmography of the island.

The first two did it as soon as they touched down on North American soil in Miami, the third, after receiving the prize in Tribeca. The event, something quite ordinary for Cubans, attracted international attention to the film and served to confirm the film’s story.

Una Noche gained three of the prizes awarded in the Tribeca Film Festival. Javier Núñez Florián, jointly with Dariel Arrechada–neither with acting experience before Lucy Mulloy selected them in a casting session–were awarded the category of Best Actor; it also obtained the Best Direction and Best Photography awards, which made it the most recommended film in the New York festival.

Then, in the 43rd Film Festival of India, Mulloy’s debut film received the jury’s special prize, the Silver Peacock, worth $27,500. In the first Brasilia International Film Festival it picked up Best Script. It next entries–in the Deauville Film Festival, in France; in the Vancouver International Film Festival in Canada; in the Trinidad and Tobago Film Festival; and in the Rio Festival–are likely to attract further awards.

In Cuba, the film opened in the month of September in a sexual health fair, organised by the National Centre of Sex Education, in the cinema La Rampa, and more recently in the 34rd International Festival of New Latin American Cine in Havana, included in the “Made in Cuba” section, in which were included audiovisual productions made in the island without the right to compete for the Coral awards.

On each of these occasions it was shown just once, and because of that only a few Cubans have had the opportunity to acquaint themselves with the multiprize-winning film which deals with a very significant aspect of their lives.

The feature film focuses on the social phenomenon of illegal emigration, especially concerning young people going to the United States, which constitutes one of the worst tragedies in Cuba because of the large number of people who have died in the process, because of the split families, and because of the brain drain of Cuban professionals (a theme I will return to later).

The principal cause of the Cuban migration phenomenon lies in the absence of civil rights such as being able to freely enter and leave the country, which has developed into a flight to realise human aspirations, which, although they are basic ones, are impossible to satisfy within our frontiers.

We are talking about a general permanent flow which Una Noche presents on a personal level in terms of the story of three young people who escape in a fragile craft, made of car tyres.

In spite of the fact that the director spent several years in Havana, gathering information for the feature, it remains suprising that, without being Cuban, she manages to get so deeply inside the behaviour of a part of the society and show in sound and vision the conduct of a section of present-day Cuba, its shortages and frustrations.

Lila, one of the film’s protagonists, tells how people leave Cuba via different routes, but she never imagined that Elio, her twin brother, could abandon her. The story begins when Elio starts to work in the kitchen of the Hotel Nacional, and there makes the acquaintance of Raúl.

From that moment on, Lila’s worry that her brother might leave her begins to give her horrible nightmares which prevent her sleeping. Right away the film starts to look into the social settings and digs about for the possible reasons for flight.

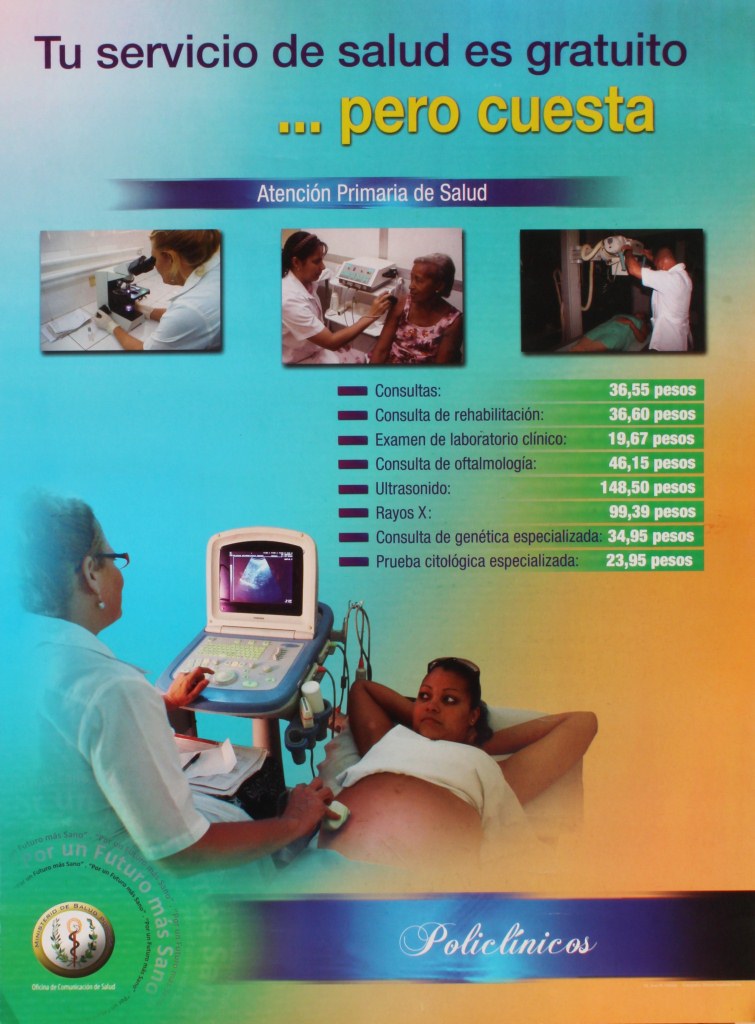

In another scene Lila comments that in Havana you can get what you want. The shops are empty, but if you know the right person, everything is for sale; a statement about the reality of daily life in the capital, which is demonstrated by way of Raúl and Elio’s vicissitudes as they seek the things they need to cross the dangerous Straits of Florida: tyres, compass, wood, a motor, food and glucose.

In each process we see highlighted the mistreatment by state organisations, the environment and language of the slums, the under-the-counter business, the loveless sexual relations, the domestic violence, the moral deterioration in the bosom of the family, the destruction and lack of hygiene in Havana, the robberies, and police repression and abuse. An asphyxiating climate which is illustrated and accentuated by rap and reggaeton music.

In the same way, the camera, which can penetrate further than the human eye, and the microphone, which can register sounds undetectable by the human ear, make incursions into the homes of the protagonists.

In the twins’ house, the macho attitudes, the disagreements between the parents and the material misery they live in; in Raúl’s apartment, the dirt, the physical and moral destruction, where his mother, who is getting on in years, and is suffering from AIDS, has to work as a prostitute, and the absence of a father, who left Cuba and does not keep in contact with them.

Along with the above, mixed in are scenes of groups of young people and adolescents behaving irresponsibly, bathing in the contaminated waters of the Havana Malecon, or risking their lives cycling about in the middle of the traffic; the old man singing dementedly in the street, whose daughter married an Italian and never came back to see him; the woman selling religious artifacts who completes the picture with false predictions in return for money.

The climax, which concludes and summarises what has happened in the events narrated, expresses the key to the story. In the boat, the dramatic conflicts, the superficiality, and the lack of foresight, show themselves.

Elio loves Raúl and Raúl loves his sister; discussions about prostitution and Elio’s and Raúl’s superficial approach to their future in Miami; Lila’s fall into the water; the shark attack, and the sinking of their boat which leads to Elio’s death, while the shipwrecked Lila and Raúl desperately cling on to a piece of polystyrene, until they are rescued by a sea scooter on a Florida beach. The film ends with Raúl’s detention in Havana, where we see dream and reality mixed up and confused.

The treatment of social phenomenon on the screen is nothing new. Information about the discovery of one of the pioneers of the seventh art, French theatre director and actor, producer of Viaje a la Luna (Journey to the Moon), George Méliès (1861-1938), shows us cinema as a way of interpreting and forming reality; and the North American film director David Wark Griffith (1875- 1948) director of Birth of a Nation and Intolerance, this last considered to be the artistic culmination of the silent screen, who looked at history as a source of cinematographic experiences.

In that sense, Una Noche, with its penetrating analysis of Cuban immigration, may be said to occupy a place in the history of social criticism in our country centred on that way of observing social reality at the margin of official apologetics.

That current, which was present in Cuba since the silent film era, started to show itself after the Revolution with the documentary PM–a short film about the ways in which a group of people in Havana had fun, which was produced in 1961 by Orlando Jiménez Leal and Sabá Cabrera Infante–which showed us a modern look at the Revolutionary reality, and became, because of that, the most problematic film in Cuba’s audiovisual history, at a time when the priority for the Cuban Institute of Cinema Arts and Industry was propaganda about class struggle and the fight against the threats of imperialism.

PM was censored and it was forbidden to show it, which produced controversy among the artists and intellectuals which led to the discourse of the Leader of the Revolution on 30 June 1961, known as Palabras a los intelectuales (Words to the intellectuals), in which he introduced the restrictive idea: Within the Revolution, everything; against the Revolution, nothing. From that moment on, culture, which precedes and transcends politics, became a prisoner of the Revolution right up to today.

In 1971, in the fictional feature film Una pelea cubana contra los demonios (A Cuban struggle against demons), its director, Tomás Gutiérrez Alea, proposed: in any time or place it is unrealistic to develop human existence in any authentic manner, if you impose limits on the process, if you define limits of acceptability of group social behaviour, if, with the starting point of a moral interpretation of society (whether it’s called bourgeois or socialist, religion or liberal) you prevent people freely discussing their own visions of the world …

The intellectual, he said, is the specialist who is most able to express clearly the semantic incoherences which have arisen within the Revolution. In the ’90’s of the last century, among the 60 cinematic works of fiction produced, there emerged important works of social criticism.

In the 21st century, among the many film directors who have made incursions into social phenomena, I would like to focus on the prize-winning creator Fernando Pérez, who has clearly shown the potential of cinematographic criticism for encouraging reflection among Cubans.

In La Vida es Silbar (Life is to Whistle) (1998), Fernando dealt with the search for happiness by way of inner liberation, the truth and social communication, and in Suite Habana (Havana Suite) (2003), he decided to convert our contradictory reality–as seen in Una Noche–into an inexhaustible source of inspiration for love and inner liberty: love of a neighbour and of a city, which, in spite of its neglected and destroyed condition, he shows us to be beautiful and full of possibilities.

In that respect, Una Noche and Suite Habana are radically different. The first one concentrates on showing the harshness of the physical and moral destruction, the second turns away from that destruction in order to show the hidden beauty and the possibilities of getting beyond it. Between the two of them they offer a comprehensive close-up on the general reality of Havana and Cuba.

On the same lines, the film producer Alfredo Guevara, President of the New Latin American Cine Festival, in its 33rd event in 2011, said, “The Cuban Revolution, which, in 1959 could …” This Revolution now requires the privatisation of Cuban Society, freed from the state bureaucracy, which corrupts everything.

The 2011 festival showed us a group of films whose common theme was social criticism: Casa Vieja de Lester Hamlet (Lester Hamlet’s Old House), a film which talks about who we are and how to understand Cubans’ lives from the standpoint of emotional commitment. Esteban Insausti’s Larga Distancia (Long Distance), in which he shows the frustrations caused by emigration in our society.

Boleto al paraíso (Ticket to Paradise) by Eduardo Chijona, inspired by real events, deals with the degradation of youth, going as far as deliberately catching the AIDS virus in order to be able to have a better life in a sanatorium. Afinidades (Relationships) by Jorge Perugorría and Vladimir Cruz, in which corruption leads to emptiness, taking refuge in your instincts, using sex as a way of discharging electricity, manipulating people near to you as a means to reaffirming your damaged personality. Martí el ojo del canario, (Martí , the eye of the canary), by Fernando Pérez, a masterwork of cinema as historical investigation.

Just as Lucy Malloy outlines some of the causes of emigration, her film offers the opportunity to show, as a kind of accompaniment, some thoughts about the migration problem in Cuba, which could be useful for those people who, having seen the film, feel inclined to get to understand a bit more about contemporary Cuba.

The economic inefficiency, the loss of civil and political rights, the inadequacy of salaries in relation to the cost of living, among other things, have had very negative effects: corruption, a phenomenon which was present in the political administrative sphere in the republic before the revolution, spread into all levels of society; while immigration, which had characterised the country since earliest times, changed after 1959 into a diaspora, that’s to say, with people moving out all over the world, as shown in the statistical data.

On 9 January 1959, the government enacted Law No.2, to restrict the right of freedom to leave the country on the part of those who wanted to go. This provision was amended by Law No. 18, which stipulated that any Cuban in possession of a valid passport issued by the Ministry of State, who wanted to travel to another country, had to obtain an “authorisation to that effect , which would be provided by the Chief of National Police”.

In 1961, the Ministry of the Interior instituted the notorious “exit permit” and laid down the length of time Cubans could remain abroad. In 1976, Law No. 1312 was enacted, by way of which permission to leave was confirmed.

In spite of these measures, the number of Cubans in the United States, who, in 1959, amounted to some 124,000, increased substantially after that date. Firstly by way of people linked to the overthrown regime or who lost their property, along with the thousands of children who left by way of Operation Peter Pan (1960-62), and then the first massive outflow via the port of Camarioca and the air bridge from Varadero, with 260,000 Cubans leaving between 1965 and 1973.

In April 1980, after a bus violently crashed through the fence of the Peruvian embassy in Havana, and its passengers requested refuge, thousands of Cubans invaded the embassy with the same intention. The result was another 125,000 Cubans left the island.

Between May and August 1994, groups of Cubans invaded the Belgian and German embassies and also the Chilean consulate, at the same time as various boats were seized.

On August 5th of the same year, Fidel Castro accused the United States of encouraging illegal immigration, and said: either they should take measures or we will not prevent people who want to go and seek their family members.

As a result, during the summer of 1994 approximately 33,000 Cubans escaped from the island, of whom about 31,000 were provisionally detained at the Guantánamo Naval Base.

During those three huge wave–Camarioca, Mariel and Guantánamo–there also occurred innumerable tragedies. Cautious estimates suggest that at least 25% of the boat people didn’t survive their journey in their variety of very different floating objects.

Nevertheless, as the main cause of the emigration was the economic deterioration and the absence of liberty, none of these laws was able to hold up these individual departures, in groups or en masse.

The Cuban diaspora constitutes a continuing process over a period of time by all the different ways of which Cuban imagination and desperation could conceive, which is reflected in the 2010 United States Census, which showed a total of 1,800,000 Cubans, which, added in to all the others who spread out all over the world, takes us past 2 million; that’s to say, that 18% of all Cubans are abroad.

Family members separated for years, or all their lives; married couples who have grown old with the pain of not being able to return to their children; kids grown up in other countries who will never more be able to see their parents. Suffering which has caused anthropological damage in many Cuban homes, where the family ceases to be the school of love, education and security and becomes instead a place for ideological disagreements, grudges and mental upsets, exactly what Lucy Mulloy was stressing in Una Noche.

The diaspora, resulting from the absence of liberties and economic inefficiency, has had, in turn, other negative effects. The rate of demographic increase was altered during the years 2001-2010 by a negative migration balance of 342,199 people, to a rate of on average 34,000 per year; a process which is converting Cuba into the only country in America with a declining population.

In the same way, it has led to a brain drain of professionals, as Cuba, which had managed to achieve a very high proportion of higher education graduates, has changed into one of the countries which is losing its professionals and technicians due to emigration.

In the last 30 years tens of thousands of doctors, engineers, qualified in various specialties such as mid-range technical people, and skilled workers, have emigrated, which amounts to a present day and potential future threat to the country.

The fact is that the illegal departures before and after the Ley de Ajuste (U.S. Cuban Adjustment Act), and before and after the migration accords which have been agreed, clearly shows it is directly related to the Cuban internal crisis.

The production of Una Noche, a film which shows the role of cinema in the way we see, interpret, and form reality; comes at exactly the moment when the Cuban government decided to modify the current migration legislation, although the change does not give Cubans back all the rights which were violated by the legislation described.

The need to obtain permission to leave the country disappears, but certain categories of Cubans, either because of the positions of responsibility they occupy, or because of studies undertaken, continue to be subject to the same limitations as previously, which will be the cause of further young people abandoning their studies and fleeing in order not to be caught by the new law.

In this sense, Una Noche is the precursor to new migratory changes up to the point where Cubans will recover the right and freedom to leave their country just like any other citizens in the world.

***

Published in German in edition 60 of TRIGON magazine, entitled “Fliegen oder bleiben?; hintergründe zum film Una noche. (To fly or to stay? background to the film One Night)

Translated by GH

25 February 2014

On April 28 the newspaper Granma published the plan for ensuring transportation to the International Workers’ Day parade in order to facilitate Cubans from various municipalities getting to the Plaza of the Revolution. All very spontaneous.

On April 28 the newspaper Granma published the plan for ensuring transportation to the International Workers’ Day parade in order to facilitate Cubans from various municipalities getting to the Plaza of the Revolution. All very spontaneous.

“My friend still ignores that this discovery was responsible for my starting to compulsively take photos a few months later. This, and the magnanimity of the Cuban Revolution, which in 1988 had forced my grandfather to move to Miami, only so that in 2005 he could give me my first digital camera. A 4 megapixel Samsung or something like that. A box of wonders.”

“My friend still ignores that this discovery was responsible for my starting to compulsively take photos a few months later. This, and the magnanimity of the Cuban Revolution, which in 1988 had forced my grandfather to move to Miami, only so that in 2005 he could give me my first digital camera. A 4 megapixel Samsung or something like that. A box of wonders.”