![]() 14ymedio, Xavier Carbonell, Salamanca, 19 November 2023 — As with almost everything deep or interesting in Mexico, very few young readers in my country know Jorge Ibargüengoitia. Don’t panic: the cult of the writer with an arduous surname – which no one forgets to mention, and neither do I – died along with 180 other people 40 years ago, when the plane in which he was traveling crashed near an implausible Madrid town, Mejorada del Campo, while the captain thundered “shut up, gringa!” against a robotic stewardess.

14ymedio, Xavier Carbonell, Salamanca, 19 November 2023 — As with almost everything deep or interesting in Mexico, very few young readers in my country know Jorge Ibargüengoitia. Don’t panic: the cult of the writer with an arduous surname – which no one forgets to mention, and neither do I – died along with 180 other people 40 years ago, when the plane in which he was traveling crashed near an implausible Madrid town, Mejorada del Campo, while the captain thundered “shut up, gringa!” against a robotic stewardess.

In 1963, Ibargüengoitia was awarded, like so many promising young Latin Americans, by that pretentious insane asylum that is Casa de las Américas. Thanks to the devastating chronicle he published after his visit, Cuba is perhaps the only country that forgot him on purpose and by ministerial decree, and not like the rest of the world, by carelessness.

As with so many things, I didn’t find a title of his again until I left the country of prohibitions

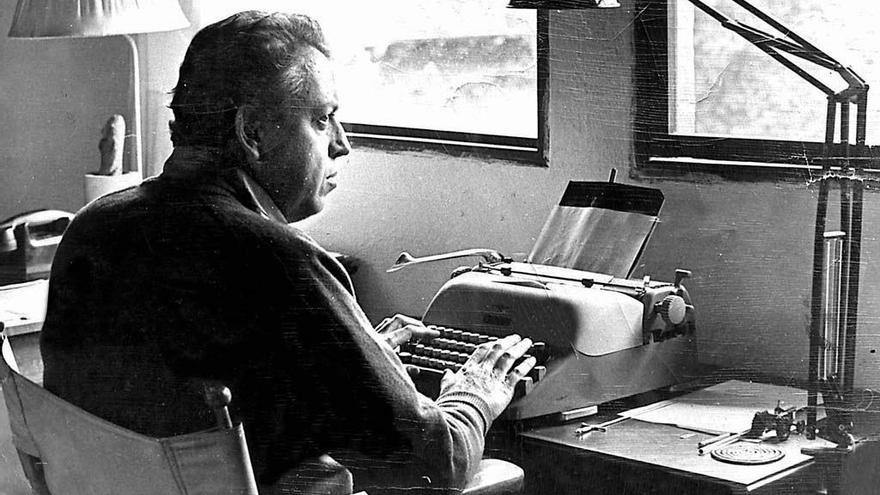

My first reading of Jorge Ibargüengoitia was Instrucciones para vivir en México [Instructions for Living in Mexico]. It was offered to me by a Mexican friend, at a time in life when I needed to be instructed, or at least initiated, in that complex profession. The planned trip never happened, but Ibargüengoitia remained in my memory. As with so many things, I didn’t find a title of his again until I left the country of prohibitions. It was Revolución en el jardín [Revolution in the Garden], in the edition of Reino de Redonda, whose prologue – by Juan Villoro – alludes to Ibargüengoitia as a man “with an astronaut’s haircut.”

That anthology contains the story of the problematic trip to Havana, where the writer arrived in 1964, to collect the prize for his novel Los relámpagos de agosto [The Lightning of August]. The previous year he had won the theater prize. He was named and invited, caught a cold and returned to Mexico anesthetized by a bottle of Bacardí. He had spent fifteen days on the Island, with his passport confiscated by the cheerful jailers of Haydée Santamaría. The stench of Marxist optimism dissipated as soon as he saw his Latin American colleagues in the lobby of the Havana Libre, “discussing the future of humanity, trying to decide which cabaret they were going to.”

He soon understood that the former Hilton, converted into Fidel Castro’s burrow, was an allegory of the entire country. On the lower floors, the humble winners of the socialist emulation or the delegates to some plebeian congress; then, the Russians and the artists bewitched by the olive green utopia; and in the dome – “the Olympus” – select guests from capitalist countries, such as the English and German executives of Mercedes-Benz, in addition to the caudillo himself.

If the official State newspaper Granma interviewed him, it was not to ask him about his literary method, but to clarify that in Havana there was “a very important writer, who was called Jorge Ibargüengoitia and admired by the Cuban Revolution.” Then came an irritating expedition to Matanzas, Cienfuegos, Trinidad and Santa Clara. On that trip he met Samuel Feijóo, who told him that none of his students had ever touched a Historia del Arte [Art History]. (I, who knew several of those students fond of doodling, can confirm it.) He didn’t have to tell Ibargüengoitia twice, and the Mexican writer left Las Villas convinced that Feijóo was at the zenith of his career: “He had managed to gather a collection of quite complex shit.”

’Revolution in the Garden’ diagnoses, with the perplexity that the Mexican never abandoned, everything that in 1971 Jorge Edwards detected in ’Persona non grata’

Revolution in the Garden diagnoses, with the perplexity that the Mexican never abandoned, everything that in 1971 Jorge Edwards detected in Persona non grata. And he did it first. No drama or bad feelings, no fear when Havana barked and bit and those who went to bed there suddenly woke up – after several magical passes of Castro – in Moscow. His fundamental lesson for literature is to write from lack of inhibition and wit, without the coarse humor that characterizes the Latin American, a level that was only achieved in Spanish – and not always – by Cabrera Infante, Eduardo Mendoza and two or three characters from Bolaño.

After several decades as a writer “for a select minority,” as he defined himself, the man with the cosmonaut’s haircut is finally getting his moment. From a cult author he has become a classic, but in the sense that he – too awake to fall into the trap – wished to interpret: “One who finishes off a tradition and renders it useless.”

Translated by Regina Anavy

____________

COLLABORATE WITH OUR WORK: The 14ymedio team is committed to practicing serious journalism that reflects Cuba’s reality in all its depth. Thank you for joining us on this long journey. We invite you to continue supporting us by becoming a member of 14ymedio now. Together we can continue transforming journalism in Cuba.