![]() 14ymedio, Yunior García Aguilera, Madrid, 28 September 2022 — I was finally able to see The Padilla Case, Pavel Giroud’s film that brings to light a disconcerting, devastating historical archive. The original material remained hidden in the vaults of the Castro regime for half a century, until now. And it’s urgent that we look back at that unburied corpse, because it’s not about ancient history, but about an urgent topical issue.

14ymedio, Yunior García Aguilera, Madrid, 28 September 2022 — I was finally able to see The Padilla Case, Pavel Giroud’s film that brings to light a disconcerting, devastating historical archive. The original material remained hidden in the vaults of the Castro regime for half a century, until now. And it’s urgent that we look back at that unburied corpse, because it’s not about ancient history, but about an urgent topical issue.

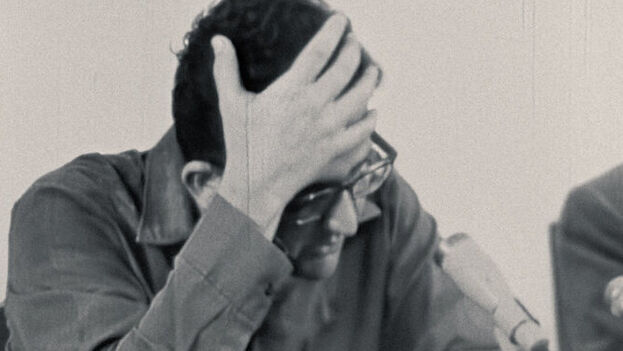

Many already knew the details of that meeting at the Union of Writers and Artists of Cuba (UNEAC) in April 1971, where Heberto Padilla revealed the Stalinist character of the Cuban Revolution. But seeing the images, observing the gestures, listening to the tone of self-criticism, contemplating the panic in the eyes of those present and feeling the sweat on the poet’s shirt, is an extremely shocking experience.

They say that Mario Vargas Llosa himself, after seeing it, confessed that he regrets not having seen the material when Padilla was still alive, because he would have embraced him and told him: “Now I believe you.” Others have stated that, with materials like this exposed to light, history will not be able to absolve Fidel Castro in any way.

I was in shock for several seconds at the end of the film. Pavel is a renowned Cuban filmmaker who had already triumphed with titles such as Tres veces dos, [Three Times Two] La edad de la peseta [The Age of the Peseta], Omertá or El acompañante [The Accompanist]. And in this last installment he turns the documentary genre into something different. It’s as if we were dealing with a thriller, a spy movie, a horror drama, an archaeological adventure. His talent for editing allows him to transform an archive filmed in an elementary way into something absorbing, fast-paced, disturbing. Beyond the testimony, Pavel gives us a work with a high cinematic aesthetic and a screen setting of something alive and current.

What happened in that room of the UNEAC was much more than a warning: it was a collective suicide. The Cuban union of writers, artists and intellectuals emasculated itself, put on its own gags , let itself be violated by a system that spilled all its authoritarian semen into the creative belly of a generation, to force it to give birth to the New Man.

Seeing the faces of those who attended that meeting is quite a spectacle. Recognizing Reinaldo Arenas among the crowd, contemplating a Virgilio Piñera who refuses to applaud, noticing the indifferent yawn of Nancy Morejón… How many of those attendees were paralyzed by fear for lives? How many started suffering from Stockholm syndrome? How much poetry died suddenly that night?

Even today, a part of the intelligentsia still has that absurd romance with a stagnant and dying Revolution. Some still believe, as García Márquez did at the time, that Cuba is a battering ram for which everything must be forgiven, in pursuit of I don’t know what utopia, like the submissive wife who endures the blows of her husband in the name of a sick love. Until when?

The protagonist of the film is neither a traitor nor a martyr. He’s a chip in a game that he cannot win or lose, a game that would leave him out, irremediably, as in the title of his book. Was Padilla sending messages to the future? Was his performance useful? Was it ethical to stab himself in front of everyone and stick a knife into the back of his friends, even if they were forewarned? Did he know how to read the world’s signs? Did he act out of cowardice, sarcasm or the ego of transcending when he was grateful for the “generosity” of the Revolution?

The Chilean writer and diplomat Jorge Edwards said that Padilla felt untouchable, because the Revolution had an image to show to the European left. But State Security would be in charge of showing him that no one escapes revolutionary terror. The poet was arrested, taken to Villa Marista, locked up, threatened, humiliated, forced to publicly self-flagellate, and what? García Márquez admitted that Padilla’s indictment did even more damage to the Revolution than his own confinement, so? The regime’s hand does not tremble when it decides that it’s time for heads to roll. No one is safe; no one is considered untouchable; no one will have clemency.

How important it is that this material is exhibited right now! How urgent it is to definitively tear the veil off those who continue to defend a mafia that hides behind the word “Revolution”! Thanks to Pavel Giroud and his team for this work, which is already essential for Cuban cinema and for Cuba.

Translated by Regina Anavy

____________

COLLABORATE WITH OUR WORK: The 14ymedio team is committed to practicing serious journalism that reflects Cuba’s reality in all its depth. Thank you for joining us on this long journey. We invite you to continue supporting us by becoming a member of 14ymedio now. Together we can continue transforming journalism in Cuba.