Translator’s note: Christmas Eve mass is called the “Rooster’s Mass” based on the belief that they only time the rooster crowed at midnight was for Jesus’s birth.

December 27 2010

English Translations of Cubans Writing From the Island

Translator’s note: Christmas Eve mass is called the “Rooster’s Mass” based on the belief that they only time the rooster crowed at midnight was for Jesus’s birth.

December 27 2010

To take away the bad and wash the good!

Translator’s note: At midnight on Dec 31, Cubans throw water from their windows, balconies, roofs to…

January 1 2011

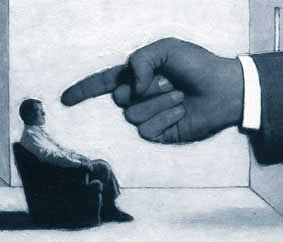

The regressive count has now commenced for the Cuban government. A swarm of hungry men and women being chased down by entourages of state inspectors, and a rampant wave of people who snitch on others has launched a new massive wave against individual initiative, the primogenial production belt of any country in the modern age, the small business. Producers of light goods, millers of animal fodder, bicycle-taxi drivers, messengers, dressmakers, and science and art tutors all enlist their marketing mechanisms: the promotion and sale of their products.

A few weeks ago when I went to Bayamo I met Mirurgia. She had arrived the night before from Cienfuegos where she bought some fabrics “at a very good price”. With these fabrics she planned to sew clown costumes for kids, whether to sell or rent. I took a look at these costumes and they were impeccable. Her sister, who lives in the United States, sends her magazines with models to get inspired by, she sends her buttons and pendants, and the end products are some costumes that look as if they came out the best “first-world” stores. I am not exaggerating. She already has orders from Manzanillo and Santiago de Cuba.

“Now, I am alone. But as soon as I recover an investment I made two months ago, I’ll employ two more seamstresses, each one working from their own homes. Together, we will try to increase production. But for now we are alone in the market,” she told me with an uplifting vibe.

Ever since he came from a Bulgaria dominated by the Soviets in the ’80s, Adrian has never been so enthusiastic about his personal business.

“I used to sell pork and lamb meat, one or two animals per week. But every time they sell ground beef, other meats, or eggs by the rationing card, my sales go down and it just pushes everything back,” he said, while showing me his “workshop”.

“I studied wood-turning. That’s my field. If I put three teams to turning, that’d be much better than the animal trading business,” he points out.

Now, he has set up three bicycle-taxis. He will paint them in about two weeks and he will rent them out to whoever wishes to use them.

Today, they rent out porches so that people can sell movies, they tear off fences and steal display counters which obstruct sidewalks, and they go to whatever extent to sell flowers, or they try to sell any other kind of merchandise by shouting out information about the product. This is the new scene of Cuban society. In response there is animosity, false optimism, and never before seen hope. Many stare at all that is happening from afar, while others take the chance and join in, but for the majority, it is not an option, it is the “only” way out.

I do not think that such liberalization of productive means is the remedy of our problems. Only freedom will get us out of half a century of failure. But this determination of so many people makes me think, to examine everything, and to go forward without personal prejudices so I can hear these stories which circulate around me. I hope my readers will not be bothered by a few other reports which will surely come during the first months of 2011.

Before the face of imminent or real unemployment, I ask myself: What can a country, that was known for its diverse confines of labor and desire, do?

Translated by Raul G.

January 1 2011

Before the end of this hectic 2010, I wish all readers health and prosperity in the new year. Some responses to messages you have sent me are still pending, some requiring deeper analysis than a few lines. I assure you I will reply in a few days, as soon as I can sit down and write in the midst of this year-end maelstrom.

We could list everything that has happened over these last 12 months, but that would be too lengthy. Suffice it to say that this year has struck a climax: the popular consensus is that the era of communist totalitarianism in Cuba is coming to an end. Castro’s socialism is collapsing.

2011 may possibly be an even more difficult year and, without a doubt, it will be crucial in many respects; I think that the main thing is that we should get ready for a new era. For my part, I’m always optimistic, though not overly confident, and I wouldn’t be able to predict the future either: the only thing I can assure you of is my willingness to remain in the network, alongside all who may wish to join me in this little virtual forum to try to broadcast from here the successes and — above all — to relay, for the readers to consider, my personal beliefs about them.

In retrospect, it seems clear that this year was intense from the start, full of incidents and milestones that have determined the precursors and aftermath of many events. The inertia has begun to break and, apparently, there is no turning back. Not to be ominous, but I see the slight and persistent signs of a civic gestation in some segments of Cuban society. I am hopeful that, this time, we have a safe delivery. None of us knows how changes will take place. The spark that will set off the process might occur in a most unexpected way, or in the most unpredictable context: it might be a drivers’ strike, a demand by a handful of disgruntled young people, or a mere push in a crowded bus. There may even not be a spark, and I hope from the bottom of my heart that there is no violence, but there will be changes, and many of us will be conflicted by them. I propose that, in the last minute of 2010, we have a moment of remembrance for our political prisoners who remain in Cuban jails because of the unfulfilled promise of this regime. Let’s not forget.

Just yesterday I talked to the poet Rafael Alcides about the Cuban situation, its generational legacy and the historic events from where it is derived. His fluid, emotional and profound dissertation climaxed with a sentence that only a poet could dream of: “Miracles usually take place under the guise of chance.” And I suddenly understood that what we are all manufacturing is just that: a miracle that may arrive at any moment, disguised in the trappings of the most unexpected happenstance. My wish for the new year is that we push the saving miracle by changing the situation that excludes and oppresses us; by finding each other in the midst of so much fog; by electing what we are and what we want to be, because it is definitely always about making choices and taking responsibility for them. I already know that there aren’t many reasons to be optimistic, but, like the poet, I choose to believe.

Translated by Norma Whiting

December 30, 2010

Left behind was the romantic stage, when a notable majority of leftist intellectuals pinned their hopes on the Revolutionary hurricane of Fidel Castro and Che Guevara.

A Cuba that clouded the reason of heavyweights in the world of letters such as Jean Paul Sartre, Julio Cortázar and José Saramago has lost its steam.

The “snob appeal” and the novelty of hundreds of poets, painters, musicians casually strolling through the streets of Havana in the ’60s, surrounded by the bustle of soldiers, where there was no hour for appointments and conversations could well last three days and two nights, said adiós long ago.

Gone to a better life are the talks on Castro’s yacht, spear fishing and drinking rum, while the guerrilla commander, with his ever-present cigar and his mania for talking without listening to others, spoke of his lavish plans that would convert the sugar-cane island into a Caribbean paradise.

Like every Utopia, it collapsed. The Cuban government no longer casts a spell on the planet’s intellectuals. It started to play hardball. The Revolution was institutionalized in the ’70s and then came the Five Grey Years. Along with the ridiculous plans dictated by the bureaucrats. The illusion died.

Cuba allied itself to the USSR and some intellectuals were condemned to ostracism, for being gay or for not reflecting the epic deeds of Castro and his Revolution in their works.

Then Real Socialism took over almost all aspects of Cuban cultural life. The pavones* came to the fore and guys such as Heberto Padilla were in prison. Giants such as Lezama or Virgilio Piñera were regarded with disfavor. Mediocre writers like Manuel Cofiño were applauded.

Some European and Latin American intellectuals broke the unwritten agreement of support and devotion for Fidel Castro. Vargas Llosa threw the first stone. It was not taken well, because a majority of the notable men of letters still believed in the righteous work of the bearded Caribbean.

In Franco’s Spain, “liberals” like the Seville attorney Felipe González and a colorful club of Iberian thinkers and artists read the extensive speeches of Castro in one sitting.

Che was an icon. To visit the shrine of the Cuban Revolution was more exciting than a tour of Paris.

Havana began its decline. Slowly it lost its allure as a dazzling metropolis. Cutting cane was an obligation for Cubans and a hobby for foreigners. Indeed, scarcities mounted and buses were rare. People dressed as in Mao’s China, but an entire people tightened their belts and pledged to take heaven by storm.

By the ’80s, the enchantment was gone. Bad news reached the dreamy European intellectuals: Cubans also wanted to earn money, dress well, wear name-brand perfumes, drive nice cars, travel the world as tourists and visit Disneyland.

Despite Cubans’ capitalist aspirations, artists in the style of Víctor Manuel, the Catalan Joan Manuel Serrat or Joaquín Sabina continued to appreciate the son of a Galician soldier who had gone to the island to preserve, at any price, the most precious jewel in the Spanish crown.

With the fall of the Berlin Wall and the disappearance of the once powerful Soviet Union, hundreds of leftist intellectuals began to look at Cuba through a magnifying glass. It was obvious: There were no presidential elections. Castro started to see himself like a newly minted Napoleon, sending his troops to different African countries.

If you have opinions which differ from those of the government, you could go to prison. And the people continue to live badly and eat little, with a ration book in force since 1962. Hundreds jumped the fence of an embassy, or launched themselves in a rickety raft on a shark-filled sea, looking for freedom and a better life on the other shore.

And now we come to the 21st century. Castro continued the same. Blinded by his Numantian position and imprisoned opponents. In 2003, the Portuguese José Saramago said, “Up to this point, I’ve gone along.” Spanish musicians, artists and intellectuals also grew tired of applauding the comandante, who now seemed like an old fraud. They didn’t care if the fault was Fidel Castro’s or the United States’. That fact is that many decided not to return to Cuba.

The death of Orlando Zapata Tamayo, political inertia, economic disaster, and the desire among a growing part of Cuban society for political changes, set off alarms and touched the sensibilities of European intellectuals.

Now the Revolution is cornered by the criticisms of cultured people throughout the world. Ana Belén slammed the door. Bosé and Juanes don’t see the situation clearly. And though still wearing kid gloves, they are aware that something is not working on the island.

Every day there are more desertions from the army of admirers of the olive-green Revolution. Few are left. Eduardo Galeano in Uruguay. A silent and ill García Márquez who says nothing, more from loyalty and friendship for Castro than from conviction.

The truth is that those who currently blindly support the Castro brothers are a tiny chorus. The great and famous flew away several springs ago.

*Translator’s note: “Pavon” means “peacock” and also refers to Luis Pavon Tamayo who headed the Cuban Culture Council during this time of heavy censorship.

January 1, 2011

On December 31, precisely at midnight, a waterfall poured from every balcony of my Yugoslav-style building. Cubans keep the tradition of throwing a bucket of water at year’s end to clean all the bad brought by previous months and to spiritually “clean” the January about to begin. This year there were infinite reasons to throw water — that precious liquid that prepares us to face everything to come — from the windows, balconies and roofs. So my husband and I found the biggest container we could and together, from our 14th floor balcony, threw its contents into the void, thinking about everything we want to leave behind. The first sun of 2011 reflected brilliantly from the puddles in the street, formed not by rain but by our desires.

On December 31, precisely at midnight, a waterfall poured from every balcony of my Yugoslav-style building. Cubans keep the tradition of throwing a bucket of water at year’s end to clean all the bad brought by previous months and to spiritually “clean” the January about to begin. This year there were infinite reasons to throw water — that precious liquid that prepares us to face everything to come — from the windows, balconies and roofs. So my husband and I found the biggest container we could and together, from our 14th floor balcony, threw its contents into the void, thinking about everything we want to leave behind. The first sun of 2011 reflected brilliantly from the puddles in the street, formed not by rain but by our desires.

Few confess aloud the full list of hopes they harbor for the next twelve months, but it’s easy to guess that an important point on every list is the need for political changes on this Island. Each defines it in his or her own way. “This has to end now,” some say. “May Raul’s reforms succeed in improving our lives,” say others. Or, “May 2011 be the year that so many of us have been waiting for,” is the cryptic declaration of some who lost patience and faith long ago.

Curiously, the word “revolution” is absent from these popular predictions, as the vast majority of citizens no longer consider it a dynamic entity, alive, in transformation. When they refer to the prevailing model in the country they do so as if it were an immovable structure, as if it were the most confining straitjacket, rigid and unlikely to adapt to the new demands of the 21st century.

All those ideals of renewal brought down from the mountains by young bearded men have given way to a government where power is concentrated in figures in their seventies and eighties, deeply suspicious of innovation. Nonetheless, in official pronouncements January 1st continues to be spoken of as the birthday of a living creature, when in fact it is the anniversary of something that died long ago. The Revolution has been buried by stagnation. The social project lies deep within the earth and the question on everyone’s mind is what date should we carve on its tombstone.

For thousands of my compatriots the Revolution died in 1968 when Fidel Castro himself applauded the entry of Soviet tanks into Prague. The fierce bear hug that engulfed us, the omnipresence of the Kremlin, the thousands of barrels of oil it sent Cuba each year, its massive subsidies and its geopolitical demands, ultimately drowned any semblance of spontaneity.

The so-called Five Grey Years (1971-1975) turned out the lights on culture, as Socialist Realism clipped the wings of our creativity and reduced us to triumphalist stories whose protagonist was always the never-realized “New Man.”

For my parents, the Revolution ended in the first months of 1989 with the criminal trial of General Arnaldo Ochoa, charged with drug trafficking. The subsequent executions, of him and others, and the purges in the Ministry of Interior, clarified for many that the anxiety to maintain power took precedence over all ideals, Marxist manuals, scientific communism and everything we had been taught in school.

For my generation, the requiem of the Revolution was confirmed some years later, with the punches and stones thrown on the streets of Havana in August 1994. When, in response, Fidel ordered the coast guard to stop patrolling the shore and to “let the scum that wants to leave, leave,” Cubans climbed aboard rickety rafts all along the coastline.

For many, their departure destroyed the remaining illusions of those who thought the Revolution was a social project “of the poor, the meek, and the humble.” It was precisely the poorest Cubans, in those days of despair, who risked the sharks and the overcrowding at Guantanamo Naval Base, where they were taken by the American forces who plucked them from the waters to wait for planes to complete their escape to the north. The thirty thousand who set sail in a single month took with them the last shred of believability of our authorities’ insistence that the government represented all Cubans.

Now we are left with too-often stated reminders of an idealized past: “What could have been and wasn’t,” people say. Meanwhile, reality negates every word spoken from the dais, leaving the black market the only option for survival as apathy casts its corrosive acid over attempts to ideologically motivate us.

It is the long funeral that never gets to the end, where the family of the departed can’t bear to shovel the sod over the coffin. Somehow, a few of them can’t shake the belief that the deceased Revolution can rise up from its shroud, reinvent itself, shake off the wrinkles and chronic diseases.

The rest of us attend the funeral, asking the poignant question, “What went wrong? At what instant did the Revolution become a cadaver?” Deciphering this question may be of vital importance to our national future. We already know many of the chronic diseases that played a part in its death: personal ambition, bureaucracy, red tape, selling out to a foreign power, and copying a model that only looks good in a text book.

What we don’t know is if it was the push we ourselves gave it, if it was our hands, our minds, which finally choked the creature they tried to create. Or if the genetics of the process were based on the chromosomes of failure from the start.

A version of this post originally appeared in Peru’s El Comercio newspaper.

January 2, 2011

“One accused is presumed innocent, as long as he has not been convicted.” The principle is regulated internationally in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, but for the Cuban state it is irrelevant, despite having pledged in 1948 to respect the rights contained in it.

“One accused is presumed innocent, as long as he has not been convicted.” The principle is regulated internationally in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, but for the Cuban state it is irrelevant, despite having pledged in 1948 to respect the rights contained in it.

When it comes time to legislate, ignoring the most basic respect for the law, what matters is to apply “drastic measures and make an example of” those who dare to take advantage of the conquests of the “Socialist Revolution.” Nor do they take time to reflect on the guarantees that the constitution of the state is obliged offer.

In 2003 the Council of State, chaired by the ailing Fidel Castro, enacted Decree 232 which imposes confiscation or loss of rights, by administrative authority, on the owners of private houses or locales where acts of corruption, prostitution, pimping, human trafficking, pornography, corruption of minors, etc. occur. It also applies to owners who lease their property without legal authorization.

The application of this provision assumes that “citizens’ ownership of housing and land is the result of revolutionary work for the benefit of working people. ” It declares it unacceptable that unscrupulous people take advantage of the socialist spoils for profit and personal enrichment.

As can be seen, in these cases the Council of State authorized the Provincial Housing Department to confiscate personally owned real estate. The procedure is simple. The Prosecutor or the Ministry of the Interior is required to submit the criminal investigations to the administrative body which, after 7 days, gives the order to confiscate.

I do not question the need to “combat with major rigor and energy” these evils. However, it is unacceptable that in the suppression of this conduct they should violate human guarantees, such as the presumption of innocence. Decree 233 is applicable regardless of what is determined by a court in a criminal proceeding.

If those prosecuted under this provision are found guilty by the courts, they are doubly penalized. They lose their freedom and their possessions. If found innocent, they are punished for no reason.

In either case there is a violation of fundamental rights. The victims of this provision do not have an effective remedy before national courts for protection from administrative acts that violate their rights recognized by the State Constitution of the island, which “guarantees the ownership of housing to those who possess a fair title.”

Those affected by Decree 232 have only 3 days after the notice of the confiscation order to challenge it — through a review before the President of the National Housing Institute — but this challenge does not disrupt the exercise of the confiscation.

The Civil Procedure, Administrative and Labor Law anticipates an administrative dispute process against acts and decisions of agencies of the State Central State that violate citizens’ rights. However, the provision issued by the Council of State does not permit the appeal of the decision of the Director of the National Housing Institute, neither administratively or judicially.

The exercise of human rights in Cuba is restricted and violated by the law. Decree 232 is an example. In its application, it destroys the presumption of innocence and places the citizen in a defenseless position.

Translated by Rick Schwag

December 23 2010

For more information about this series of posts, please click here.

From “The New Man”

Dear comrades, close comrades,

Those who now warn us, memorializing the life and work of Papito, Pavón and Quesada, instead of ridiculing them as flunkies, or treating them as model sacrificial snitches from a gray period of our history, should raise a monument to them, the highest.

Because those who vent against them today, in the name of our moral purity that, don’t forget, is also unreal, also epic, if they have any glory, that which they say fits into a grain of sand, they owe it to them.

Neither the most vigorous combatant nor the most ferocious adversary has contributed so exactly disproportionately to my creation than Papito, Pavón and Quesada, who, with their dauntless imprint, converted me into the most perfect historical construction of the people.

I am the most exact result of this now excessive dialectic process of the middle century. And when I say “dialectic,” I’m referring to the custom derived from the contradiction, the struggle of opposites, antagonistic or not, although preferably of the first, the most drastic conservatives, because with their defeat they make irreversible the evolutionary, historic processes, creating the collective conscience that sweeps them away from the future, to not be negative examples, unrepeatable, although irreversible,

Papito, Pavón and Quesada are, without a doubt, part of this pattern. But also those who inject a memory of the institutionalized terrorism, at the state level, the mistrust (mutual and self), the paranoia, the fear of the Other (whether it’s myself, my tortured conscience), that which is not (in so far as being ontological, that’s good, but fundamentally ideological) the same as I, someone similar. The fear of otherness (Jiminy Cricket, leading you on the right road) was not aroused or undone with/by the dirty work (hidden, secret, clandestine) of Papito, Pavón and Quesada, but above and beyond their “Five-Year Gray Period” it extends, was extended and – if we don’t do something today – will be extended, as it menaced with all awareness and allusive capacity, poetic, let’s say, from the “small screen”, the administrators of our power.

Yes, Gray Period paranoia aside, it’s frightening to see that, when they were buried they managed to (dis)simulate themselves in the tomb, where some of us go to lie, to create unarmed defenseless, specimens that appear (we might wish) extinct, they emerge from the silent obscurity of forgetfulness, upon emerging from the back of the small screen (that’s to say from banality, nothingness or The Difference, which is the summit), as a sample demonstration of media proof. Papito, Pavón and Quesada have complied with the cause to which one day they swore to dedicate themselves, subordinate their lives for, at all cost, repressing them, extolling values, contrasting them, excluding them. Omission doesn’t work, not even with them.

Those who saw them on TV comment that, simply seen and not doubting it, I add, they didn’t seem repentant, one of them even said that nothing tortured his conscience. They gave no indication of reviewing their bad steps, those who from their intrepid trenches of mistaken ideas, intolerance and premeditated errors, some treacherous or coldly calculated (while drinking cold beer, on the Patio of the Cathedral, according to what they tell me), working overtime into the wee hours with the delight of a goldsmith, gave me the master touch, the finish.

It’s not paradoxical to say that with their excesses Papito, Pavón and Quesdad stopped delineating at least my contours, extracting me from the utopia of that time, up to achieving what I am now, or we are. In their eagerness, in order to accomplish unthinkable renovations, in a process of reaching the high dream of being a different human, united in solidarity, utilizing the method of standardizing society, they contrasted it so much that they opposed me, at least like a paradigm, trying to institutionalize in place of man until then sacrificed, worker, conscious of his revolutionary role, that I was blindly obedient, which formerly giving one’s all for an ideal accepts as good constitutional violations, the alienation, disposal of human rights and the installation of dogmas and prejudices, the most diverse exclusions like rational, honorable, and valid social behaviors.

So that I, the idealized, monotonous, intangible new man, after passing through the filters of the numerous Papitos, Pavones and Quesadas, generalized in every social sphere of the “Five-Year Gray Period,” have materialized into the youth and adults of today: writers of merit (whether they’re gay or not, who cares anymore), obscure musicians of the music stand, or precious stones in tune with April, modern dancers or not so much, Moorish boleristas or Mountain-man soneros, half sorghum or full sorghum, drunken or blurred jugglers, broke or with cash, with trim haircuts with little lines shaved into the sides, mop-hairs initiated into Santeria, protestant christians, salty, with too much on their plate or salty, with no plate at all, plumbers, bricklayers, shoemakers working (for themselves or on the black market), painters of little boats, escapees on a raft, bakers without oil, deserters of salsa, those of the rains-on-roofs or even though you know that later you’ll be going, improvisational singers of desperate rural music, ex-cane cutters, we give them posts and we relieve posts, the thieves on the bus, the transvestites of Reina and other artists, because we are all them, we have to make art or crafts under certain circumstances called “special,” which during that “Five-Year Gray Period” – which has not died out, like a good fire provoked – converted them into their appeasing victims or systematic opposition, many of them equally broken and not claimed…

In the end, at the vertical level of our society, all owe it, we all owe who we are to the “Five-Year Gray Period”, when by virtue of the laws like those of vagrancy, the centers of work converted themselves, instead of centers of material production with the goal of benefiting the people, into centers of inflated production, subjective, abstract, of rehabilitation.

Yes, we, the new or repaired men of today, if we apply to everyone the double standard that we owe to the Papitos, Pavones and Quesadas and company (they weren’t working alone, of course, they had lackeys and even figureheads, so as not to say hit men), all the dignity that now they proclaim, we proclaim, a proclamation coming from the e-mails that we interchange, with no little hope of victory, which we are owed, in place of ridiculing them (inquisitorial manner of saying “skinning” them) or putting them again on the public pillory or pouring on them so much earth that they appear dead, to show them our most profound recognition, and raise them to the highest peak of Mt. Turquino, of The Havana Libre Hotel, an unforgettable monument to tedium, with one entry per turn and for heterosexual couples, of course, as God ordered in the ’70s, but paying the hardy cover in Convertible Cuban Pesos, the same as now, in these years of 2000, just as God has decreed that we all pay.

Sincere greetings from

The New Man

Translated by Regina Anavy and Los Iguanitos

January 31, 2007

For more information about this series of posts, please click here.

From Consenso digital magazine

The digital magazine “Consenso“* is putting at the disposition of its readers a portfolio which contains almost all of the texts that were circulating via electronic messages among numerous Cuban intellectuals in the months of January and February of 2007, and which comprise a historic virtual debate about Cuban cultural policies of the last 48 years.

As is well-known today, everything began when the young writer Jorge Ángel Pérez sent a message expressing his surprise and disgust at the Cuban television appearances of various personages who, in the 70s, were responsible for one of the darkest periods in national culture. Almost immediately the essayist Desiderio Navarro, the art critic Orlando Hernández and the writers Antón Arrufat, Reinaldo González and Arturo Arango joined the debate using e-mail that circulated among hundreds of addresses inside and outside of Cuba.

The portfolio we show here contains a hundred or so participants, many of them with more than one message sent. Messages appear from inside Cuba, those which arrived from overseas, those signed by relevant figures, and those subscribed by persons unknown, where pseudonyms were not lacking. There are texts, photos and caricatures; there are the academics and the passionate and from there, those of all participating positions. The sources have been diverse; from the Granma newspaper to the digital magazine Encuentro on the ‘Net, but fundamentally we have received generous help from friends who have passed to us messages received by them.

To ease searching, each participant occupies a page with all his messages organized chronologically and on each page the reader will have in sight a dynamic index in alphabetic order through which he can access the rest of the participants.

We beg our readers that if they discover they are missing messages to please send them to our mailbox: consenso@desdecuba.com and, more importantly, through our pages please give continuity to this debate, for nobody definitely has considered its conclusion a given. This portfolio will stay open as long as the problems posed are not solved. The digital magazine Consenso inaugurates with this debate its portfolio space in which — in free (gratis) form — we will open a space for those who desire their own.

* Translator’s note: Consenso translates into consensus. In this case it is the title of the publication being referred to, not consensus in its literal state.

Translated by: JT

January 31, 2007

For more information about this series of posts, please click here.

From Jorge A. Pomar

Are the intellectuals waking up?

Everything in Cuba is as rotten as in Hamlet’s Denmark. It all stinks. Even the Horaces of the UNEAC (Cuban Writers and Artists Union) stink. Yet another proof of this is the electronic call to arms just emitted by Desiderio Navarro in Havana as a result of the unexpected resurrection of Luis Pavón, once powerful, if not all-powerful, President of the National Council for Culture, via the programme Impronta (Imprint) on Cubavisión. Auturo Arango and Reynaldo González have already broken a lance on his behalf in what has become a promising campaign. Whatever the objections of those of us who are not on the inside — and it will be seen that mine are many and forceful — we should not only welcome the initiative of the combative as ever Desiderio, but also support it wholeheartedly, heaping fuel on the fire of good faith; that is, with the intention of forcing them to draw conclusions and see themselves as others see them.

But it is no less true that the arguments made leave a lot to be desired. Which is partly explained, of course, by the risk that they are running by sending such a protest on the Intranet. What is not easily explained is what can be inferred from their captious arguments, the implications and underlying meanings derived from their words.

According to all three — who have signed up to the ideas of the so-called ‘criticism tsar’ in Cuba, Ambrosio Fornet — Pavón and a couple of minor civil servants (among them Lisandro Otero, who they are careful not to mention as he is currently fashionable in the vile on-line literary magazine La Jiribilla, but he was Pavón’s second-in-command) were responsible for an unfair cultural policy (1967-1971), now happily left behind. In their eyes, with the public reappearance of Pavón the shadow of the Leviathan of the ‘Pavonado’ can be seen again, threatening the freedom (?) of the ‘true’ creatives.

It is a version of the tale of the noble king applied to his majesty Fidel Castro, who in half a century has never shown signs of acknowledging the corrupt actions of his evil ministers. In fact, the ‘silence and passivity of almost all of them’, the ‘complicity and opportunism of many’, which Desiderio puts in brackets, are still characteristic of the attitude of the Island’s intellectuals today. The troubles of writers and artists did not finish in 1971, as Fornet would believe, or have the rest of us believe.

Pavón, who was certainly no angel, he has been the favourite scapegoat since 1971 of those who, rightly or wrongly, like to think of themselves as his victims. It would take a casuistic analysis, a task in which I have no interest, to determine the role that each played then, or plays now. However, Pavón’s offence consists, no more and no less, in having been the figurehead, the instrument of the Revolutionary Government which carried out mercilessly the cultural policy of a Revolution which the members of the UNEAC applauded, and still applaud in their show of protest — rapturously at a time of jails bursting at the seams and firing squads overburdened with work. Those ‘plentiful 60’s’ of which Desiderio speaks were, in fact, the cruelest years of Castro’s rule.

After swallowing all this rubbish without complaint, after condemning like Cain colleagues who fell from grace every time they were asked to do so, and above all, living rather better than the great unwashed thanks to the subsidies in dollars (now CUCS) of the UNEAC, likewise the prizes and the trips abroad etc., I fear it will be sufficient for the charming (with the literati almost always) “comrades” of State Security to give them clip round the ear, if they haven’t done it already given the gravity of the situation, for them to start to walking crab-wise again. It would be a pleasant surprise for me to discover that I am wrong. Clearly, they do not feel any guilt, educated Little Red Riding Hoods from the story of the good king, constantly misinformed. however, their greatest merit in the end of the Five Gray Years (which is now a “Dark Half-Century”) has been to live with their backs to the national drama, shut in their ivory towers during the three ashen decades of the wolverine Pavón.

On the other hand, they know very well the price of protest. That’s why, out of an instinct for self-preservation, they have never dared do it. When, to take one example, in 1989 I protested about the upcoming execution by firing squad of General Ochoa and his company during a plenary session of the UNEAC, they all responded with silence. “You’re crazy! and immediately, by order of Abel Prietrio, who was chairing the session they moved on to the matter which really concerned them: How to pick up a few dollars making some artistic or literary contribution to the then resurgent tourist industry?

Willingly or by force, far from supporting it, they signed the UNEAC’s 1991 official protest against the Letter of the Ten, a range of moderate reforms which attempted to reduce the misery of most Cubans. In contrast, they didn’t oppose the execution in 2003 of those three young, impoverished black men, who were only trying to get away from the paradise famed in so many poems and tales. And of course they kept very quiet about Raul Rivera and those condemned in the Black Spring. The list of their public silences (in private they sometimes dare to express their condolences), complicities and collaborations could go on indefinitely.

Why not, then, give Luís Pavón, who in 30 years could well have reconsidered and be a different man, the benefit of the doubt? Any court would consider his crime “spent”, and in any case, no life was lost. Not so the pristine Reynaldo González, who makes no bones about bringing up the “Nazi Holocaust of the Jews”. Incidentally, anticipating a possible return of the ‘perestroikist’ (let’s not forget, please) Carlos Aldana, he encourages the fear that “the tough guys” might return. Reynaldo, get this for once: “the tough guys”, with a healthy bunch of opportunists and social climbers of all kinds, now have a stronger than ever grip on power and “among the indolent curled up at their posts” the more intellectuals gather, the more they keep their heads down. Not all of them, of course. Quality counts too.

The “Cuban intellectual field”, Arturo, has not “become over-complicated”; rather it has been corrupted to the core. The “luck of the revindicated blacks”, and of those who demand nothing, is still as black as their skin. On the television they are only given roles as slaves, guerrilla fighters and beggars; in real life they are forbidden access to management posts in the dollar economy. Ask “Ambia”, who I heard tell the story again in a video filmed in his lovely Parque Trillo. Homosexuals have made some progress but, outside the world of culture, they are still stigmatized. Tolerance is not the same as acceptance. The “belligerent right” and “passive pragmatists” you speak of, what are they, if not the eloquent result of the “success” of the current culture policy? Give them their full names, if you would. As for the rest, no one thinks, or disagrees, “from the left and from the revolution”. It is good enough to do it with the brain, which is divided in two hemispheres for a reason.

To state that Fidel, with his sadly famous “Words to Intellectuals”, was trying to dispel the fear of “those creators who are neither revolutionaries nor counter-revolutionaries” (Desiderio mentions Heberto Padilla, whose name he doesn’t use, as it’s taboo) seems to me if not an act of political procurement, at least an extravagant piece of deliberate nonsense. It’s laughable. The leitmotiv of this speech, plagiarised from Mussolini by the way, leaves no room for doubt: “Within the Revolution, everything; Against the Revolution, nothing”. Tutto nello Stato, niente al di fuori dello Stato, nulla contro lo Stato, declared Il Duce on 28 October 1925. Translate. You’ll remember, nostalgic Desiderio that, after listening to Fidel in the Function Room of the National Library in June of 1961, Virgilio Piñera took the floor and mumbled, “I am very much afraid. I don’t know what I am afraid of, but that is all I have to say”:

And so, if our ineffable ‘creatives’ protest now, about this televisual trivia heavy with bad omens, it’s more because of their simple professional selfishness. The privileges and cash benefits which, in order to keep them onside, their cultural paymaster Abel Prieto has granted them with the blessing of the Great Leader. The suffering, the deprivation, of the vast majority of the population, doesn’t seem to matter to them in the least, outside the world of literary fiction. Although we know that, inside, they too suffer, From bad conscience.

The television programme given over to Pavón does, at least, break the routine of the usually yawn-inducing schedules in which an important place is given to the self-promotion of the victims of that bête noir of Cuban culture. At last something worth seeing on Cubavisión, among all the usual ritual, triumphalism, creole tradition and 19th Century art! Even though it’s just to work up some alarm, like Desiderio and company. Alarm that I share, since it is very clear that behind the grandiose demands of Pavón lies the hand of the Raulist generals. Bad omens for art during the approaching handover of power. With all this, as far as I’m concerned, I would consider it acceptable as long as it ended the misery of the population and, above all, doesn’t last longer than the biological clock of the Castrist old guard. Art can wait. That’s how direct and right-wing I am.

Besides the reservations I’ve set out, I shall not hesitate a moment in supporting a protest that, although it strikes me as timid, wet and confused, could be the trigger for a far-reaching political and ideological debate. My respects to Desiderio. Congratulations! Our intellectuals have to start somewhere. In the end it might be that minimalism works better in politics, which tolerates it more, than in literature, where it requires higher levels of excellence. If only this unpleasant media event might serve to waken the intellectuals from their long, Sleeping Beauty-like, slumber, and give them courage to include all Cubans in their fair demands and, using their energy for nobler causes, finally start to play their proper role in an Island that is at the most important crossroads in its history, but doesn’t appear to know where it’s going. About time. Now we must hope they don’t disappoint yet again.

Jorge A. Pomar

Germany

Translated by: Jack Gibbard

January 2007

The flower, which last night was just a pregnant button, opened its petals at dawn and flooded the room with its fragrance. The dim light of the rising sun began to illuminate it. A stillness encompassed all the space and objects around it: the armchair upholstered in blue, the round table of red wood and white marble, two wicker chairs, the old sofa, a bookshelf with glass doors. The girl who slept on the sofa, covered with a golden blanket, breathing so faintly that she seemed to form a part of the inert objects. So thought the flower! It felt the two leaves that adorned its stem stretch and, looking down, watched them briefly. They stared back with a tinge of sadness. Flower and leaves longed for dewdrops and wind. An unnerving thirst began to torment it. The girl moved and stretched her arms. The movement drew the bedspread that covered her and revealed one of her shoulders as golden as the gold of the quilt. Then she opened her eyes and a blue light, as strong as the sun, lit up the flower, making it look metallic. It looked with her new color and a sense of vanity seized it. It was a different flower.

December 31 2010

Since the publication of the Civic Manifesto addressed to Cuban communists, reproduced in this blog after it first saw the light of day on December 13, 2010 in the new digital site “We Ask to Speak” to which I created a link, many regular readers and other friends inside and outside Cuba have expressed their interest in signing the document. Originally, said Manifesto was not designed to collect signatures, so it shows only the eight signers who participated in its first debate and composition. However, due to the reception it has had among many readers, it has been replicated in several other digital sites as you have requested, and this January, the option for anyone wishing to sign it, independent of their nationality, ideology or political affiliations,will be added. This is a civic message, not of a partisan stance.

You can also contribute to the dissemination of the ideas presented in the referenced document by e-mailing it to friends and relatives within and outside Cuba. I will inform you as soon as possible when it is available for signing on the website cited above, where it was published initially. As co-author of the Manifesto, I appreciate the support you have given it, and I encourage whoever shares the proposals and ideas it contains to sign it. Thank you for your invaluable solidarity and support. A hug to everyone. Miriam.

Translated by Norma Whiting

December 28, 2010

December 31, 2010

Eliseo, 39, is considered a public benefactor. A guy who is always welcome. For a decade, this Cuban American has been a ‘mule’. He resides in Miami and makes some fifteen trips to the island every year. Sometimes more. Right now, from his mobile phone, he calls his usual driver to pick him up at the entrance to the Jose Marti International Airport, south of Havana. He loads a bunch of bags and briefcases. He will be in Havana for one day. His mission is to unload the 150 pounds of food, medicine, electronics, clothing, shoes and toys, among other things, in a house that he trusts, where later they will take charge of delivering them to their destinations.

Eliseo, 39, is considered a public benefactor. A guy who is always welcome. For a decade, this Cuban American has been a ‘mule’. He resides in Miami and makes some fifteen trips to the island every year. Sometimes more. Right now, from his mobile phone, he calls his usual driver to pick him up at the entrance to the Jose Marti International Airport, south of Havana. He loads a bunch of bags and briefcases. He will be in Havana for one day. His mission is to unload the 150 pounds of food, medicine, electronics, clothing, shoes and toys, among other things, in a house that he trusts, where later they will take charge of delivering them to their destinations.

Eliseo has set up a small business operating at full throttle, especially in the month of December. He charges $5 per pound of food or medicines, and $10 per pound of other items. To move certain goods controlled in Cuba, he discretely slips a hundred-dollar bill in the pockets of the customs authorities. In Miami he also greases the palms of air terminal officials. When George W. Bush turned the screws on the embargo against Castro, Eliseo always wrangled it to bring products and sums of money that violated U.S. laws.

“Now with Obama everything is easier.” The current occupant of the White House has taken steps to facilitate family relationships. Since December 20, you can send up to 10 thousand dollars via Western Union. On top of that, residents of the island can collect it in convertible pesos. Facing the urgent need of the “imperialist enemy’s” greenback, the Cuban government eliminated the 10% duty on the dollar.

On October 25, 2004, an angered Fidel Castro, supposedly caught laundering 3.9 billion old dollars in the Swiss UBS bank — something prohibited by the embargo — he announced a 10% tax on the dollar during a television appearance. Starting on November 8 of that year, the only currency that circulated in Cuba was the Cuban Convertible Peso (CUC).

Remittances from family members and the sending of goods by “mules,” in large part brace up the fragile and inefficient island economy. According to international organizations, through remittances alone the government allows some billions of dollars to enter the country every year. Darío, a 52-year-old economist, thinks it could be double that. “There is a lot of money that isn’t accounted for. It’s a source that permits the investment of money free of the State’s nets. The government knows it and won’t lose sight of it. It’s probable that in months to come they’ll stimulate it even more.”

In Miami, dozens of agencies are dedicated to the shipment of packages and money to Cuba. Meanwhile, Cubans on the island ceaselessly ask their relatives for things from disposable toilet wipes and tennis shoes to laptops and plasma televisions. If the embargo were to end, the interchange of merchandise and capital could exceed 5 billion dollars annually. And if the Havana regime would repeal absurd laws that prevent Cuban-Americans from investing in the country of their birth, the numbers could triple.

What’s certain is that the embargo hasn’t prevented families on the island from receiving money, by one means or another. Neither foodstuffs, medicines, nor other articles. Eliseo assures us that he earns almost 2,000 dollars in profit each month. “If it’s the end of the year, a little more. In whatever way, despite the fact that I live off of this ‘business’, it satisfies me to see the people’s joy when they receive their packages, or while you count out a bundle of bills for them.

But above all what sticks with me are the hopeful faces of children when you see them unpack toys and sweets.” Moments like those make Eliseo feel like a tropical version of Santa Claus. The families on both shores appreciate him.

Translated by Rick Schwag with a little help from JT

December 30 2010

Once again, my friend Maricarme gave me a reason to write a post.

Once again, my friend Maricarme gave me a reason to write a post.

She was very tired, for she has spent her time, much like the majority of the women in my planet, cleaning the house, organizing wardrobes and sideboards, dusting off decorations, and stretching out the little bit of cash she has just to be able to greet the new year the way it should be.

She wanted to make a good cold salad for the 31st. Worn out from so much end-of-year cleaning, she went out on a search and capture for food. As she did so, she passed by a place where they sell pork meat (the only one that does) and out of the corner of her eye she saw the pork chunks, and this image stayed in her brain. When she arrived at the hard currency kiosk, without realizing her mistake she asked the attendant, “Do you have meat?”

The dispatcher was astounded and responded, “No ma’am, nothing like that”.

So she asked, “By any chance do you have a can of fruit”?

“No ma’am, not that either,” and he continued, “but look you should go home, take a good shower, go to sleep for a while, and later, when you’re more refreshed, you can come back here and I’ll be glad to help you.”

My friend tells me that, upon returning to her house, she could not control her laughter for the scene she had just created.

Translated by Raul G.

December 30 2010