“The Little Email War,” “Little Glasnost,” “Rebellion of the Intellectuals” or “The Created Situation,” have been some of the names used to baptize this phenomenon which I prefer to call, “words of the intellectuals” (with the “of” in bold and underlined). Evidently a hole has been opened in this Pandora’s box (which was a gift from Zeus himself), where it is not the evils that populate the world that are escaping, but rather the outrages committed against freedom of expression.

I promise not to use this space for personal complaints, in the first place because I feel a profound gratitude to those who, in December 1988, banned me from practicing the profession of journalist. To them I owe my freedom, which I exercise from Cuba, although sadly not in the media permitted in Cuba.

As it is not possible to answer, argue or support each deserving idea, because that would imply writing a book, I will limit myself to giving my opinion about what I believe is fundamental in this issue, which after all is not, not even remotely, the appearance on the small screen of those who once were the obedient adherents of a policy. What seems to be clear to everyone is that there are open wounds, self-criticisms to make and discussions to foment.

I can understand the horror of the newly vindicated, faced with the renewed vindication of their executioners; what I cannot seem to understand at all is the simplicity of confusing the systemic with the causal.

Just like a bus that is already full, those who are already on the first step of the discussion ask to close the door because there isn’t room for anyone else, but those of us who are left behind, those who here are below, we think differently.

I believe that the basis of all the wrongs that have occurred is the intolerance of difference, which is not limited to the nearly defeated intolerance of different religious beliefs, or to the repudiation of different sexual preferences. I am speaking about the unconquered intolerance of diverse political opinions. I would like to know on what general principle we can build tolerance for one particular kind of diversity without applying this to other kinds of diversity.

Since that fateful day in which the cultural politics of the Cuban Revolution was subjugated to a sectarian phrase — Within the Revolution, everything, against the Revolution, nothing — the abyss opened. Because from that moment a group of people were conferred, or conferred upon themselves, the right to define the boundaries of what could be catalogued as revolutionary, meaning what could be published, shown and disseminated. And since the creators of literature, painting, music or cinema usually fulfill themselves when their work becomes something tangible for the public, they begin the create in that direction and there begins the self-censorship; because there is only one way to be sure that what we do cannot be classified as “outside of the Revolution,” and that is to do only that which is clearly for and within the Revolution.

That gray five-year period was only the act of drawing the dividing line a few meters closer to the border. The original sin was to conceive the border.

Some of those who are participating in this discussion are not disputing the right of the government to decide whether to publish a work based on its political affiliation. The only thing they are contending is that they and their work should be considered unwavering supporters of the Revolutionary line. Others want to go further, which is why, in this debate, many things are being discussed at the same time.

Víctor Fowler, with his habitual lucidity, introduces the idea of a “catalog of practices of cultural violence.” All of the anecdotes fit into this catalog: prison for the translator of the prophecies of Nostradamus, the famous Padilla case, the firing of Eduardo Heras, the sanctions against Norberto Fuentes, the ostracism of so many illustrious names: Cintio, Eliseo, Lezama, plus the endless list of the unknowns, as always, who in obscure cities of the country defiantly read a combative poem in a literary workshop session or who, in a provincial radio broadcast, dare to introduce an uncomfortable song by Frank Delgado. The question is how far do we take this list, and if we should pay attention to those already on board, who are shouting to close the door once and for all so the journey can continue, or if we should continue letting more people get on until the bus bursts.

Who gave the order to close the expositions of the group Arte Calle? What should we call the decade in which they banned Pedro Luís Ferrer? What color was the five-year period in which Antonio José Ponte was expelled from UNEAC? Who was the Minister of Culture when the movie “Monte Rouge” was blocked from being shown in the Cinema Festival? What, if not “The Black Spring of 2003,” should we call that moment when the poet Raúl Rivero was imprisoned?

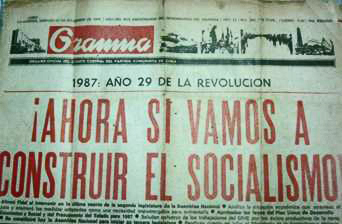

Esteban Morales himself, former dean of the Faculty of Liberal Arts, classifies as “Saturn devouring the children of the Revolution” not just subordinates of Luís Pavón, but militants of the Communist Party who, in the seventies, carried out relentless purges in the school of journalism, and who today publish in the daily newspaper, Granma, and no one bothers them.

And all this is being discussed today perhaps because some advisers in the Cuban Radio and Television Institute (ICRT) who work on the program Impronta [Imprint] are just historians versed in the 19th century and wouldn’t know who directed the National Culture Council 30 years ago. I wonder what would happen if, as a part of “50 Years of Victories,” someone were to recount the exploits of Hubert Matos in taking the city of Santiago de Cuba, or if someone who does not know the secret versions of the story, speaking about the events of Granada, would mention Colonel Tortoló as an emulator of the Bronze Titan. I bet that nobody would ever make the mistake of making a Impronta episode about Doctor Hilda Molina, however much she deserves it.

What really happened is not that one day it was mentioned to someone that it deserved to be buried in silence, but just the opposite; it’s that it has been too quiet for too long, and not only in the area of culture. As the critic Orlando Hernández has bravely pointed out, “It would be very sad if all this fell into the ridiculous Complaints and Suggestions Box at the Ministry of Culture, or if it were converted into a minority’s collective catharsis.” I believe that the criticism or self-criticism remains unresolved not only in the case of the First Culture Congress, which changed its name in its second session to become the Congress of Education and Culture. The Military Units to Aid Production (UMAP), the Revolutionary Offensive of 1968, the repudiation rallies of the 1980s, the unmet Food Plan of 1990s, the sinking of the tugboat 13 de Marzo, and the infinite lists that so many victims could rightfully assemble, are also in need of a self-criticism; to do otherwise would make it very difficult to honor someone on television without running the risk that the person interviewed would have another “imprint” in his illustrious biography.

Not only revolutions, but also history in its entirety, is staged by men who,in carrying out the projects they put forward, experience successes and failures, greatness and baseness, nobility and villainy. Cuba’s is far from a celestial history, though many have insisted on sweetening it. It seems as if once again someone has tried to marry us to a lie and to force us to live with it, but fortunately, someone also has taught us that it is better to let the world collapse than to live a lie.

I don’t want to finish this intervention without referring to the cryptic Declaration of the Secretariat of UNEAC, published on Thursday, January 18.

To say that the cultural politics of the Revolution, established with those Words to the Intellectuals — Within the Revolution, everything, against the Revolution, nothing — is irreversible, is to affirm that Luís Pavón did not manage to reverse it and therefore only was consistent with it to an extreme degree. In that we are in agreement. What I cannot agree with is the element of terror the text introduces with the mention of a supposed annexationist agenda on the part of those who have wanted to take advantage of the situation created. I call on them to show a single paragraph of the debate with the stink of annexationism. Although it is suggested that this is the consensual response of the debate’s initiators, evidently it is a text that Leopoldo Ávila would proudly sign.

I propose a full debate on all these matters. Since UNEAC — the Cuban Writers and Artists Union — has decided not to hold its proposed congress, now that the Communist Party of Cuba has not held its either, we will do it ourselves in a theater, at the ballpark or in the middle of a field, without the rapid response brigades to impede its meeting, and where the entire world can speak, the communist, the social democrat, the Christian democrat and the liberal, and if the annexationists have something to say, we will listen to them also.

Finally it seems healthy to me that those of us who participate in this discussion do not share a common position. We are not going to repeat the model affirming that “this is not the moment to have divergences among ourselves because we should unite against the common enemy.” Much less will we proclaim something like, “Against the reign of Pavón everything, for the reign of Pavón nothing.” Please, let us not start in the same way. Fortunately, like Pandora’s mythical box, the only thing that hasn’t escaped is hope.

Reinaldo Escobar

Translated by Ariana

January 31, 2007

Last weekend I conducted an interview with Guillermo Fariñas, which can be read shortly in the journal Coexistence. Among the questions that might become old news by the time the conversation is published, is this one which I am putting here on my blog. I share Fariñas’ optimism and apprehensions on this subject, and consider it a topic of enormous importance, because the release from prison of the final opponent would mark a milestone on the path to a claim we have made so many times: Let differences be decriminalized!

Last weekend I conducted an interview with Guillermo Fariñas, which can be read shortly in the journal Coexistence. Among the questions that might become old news by the time the conversation is published, is this one which I am putting here on my blog. I share Fariñas’ optimism and apprehensions on this subject, and consider it a topic of enormous importance, because the release from prison of the final opponent would mark a milestone on the path to a claim we have made so many times: Let differences be decriminalized!

As I have no talent, not even for beating out a rhythm on a door, the artists who play some instrument with virtuosity awaken feelings in me between admiration and envy. When, for example, Frank Fernández moves me with his interpretations of Sergei Rachmaninov or Frederic Chopin, I can hardly bear my own incapacity to do something similar. I feel like an idiot.

As I have no talent, not even for beating out a rhythm on a door, the artists who play some instrument with virtuosity awaken feelings in me between admiration and envy. When, for example, Frank Fernández moves me with his interpretations of Sergei Rachmaninov or Frederic Chopin, I can hardly bear my own incapacity to do something similar. I feel like an idiot. In his fourth opportunity to take advantage of the traditional date of July 26 to launch at least one sign of change, Raul Castro declined the privilege of addressing the most important event of the year, delegating the honor to the political leader who personifies intransigence: José Ramón Machado Ventura.

In his fourth opportunity to take advantage of the traditional date of July 26 to launch at least one sign of change, Raul Castro declined the privilege of addressing the most important event of the year, delegating the honor to the political leader who personifies intransigence: José Ramón Machado Ventura.