Category: AUTHORS

Cyber-police and Firewalls to Control Cuban Internet / 14ymedio, Orlando Palma

![]() 14ymedio, Orlando Palma, Havana, February 15 2015 – Only a few weeks after Barack Obama’s decision to allow American telecommunications companies to offer their services on the Island, Raúl Castro’s government is making it clear that the virtual world will not exist without limits. Lately, official spokespersons have taken on the task of explaining to the general public that low connectivity in the country is not due to a government decisions, and this seems to be the purpose of the First National Computerization and Cyber Security Workshop, which is scheduled to take place on the 18, 19, and 20 of February.

14ymedio, Orlando Palma, Havana, February 15 2015 – Only a few weeks after Barack Obama’s decision to allow American telecommunications companies to offer their services on the Island, Raúl Castro’s government is making it clear that the virtual world will not exist without limits. Lately, official spokespersons have taken on the task of explaining to the general public that low connectivity in the country is not due to a government decisions, and this seems to be the purpose of the First National Computerization and Cyber Security Workshop, which is scheduled to take place on the 18, 19, and 20 of February.

According to the official newspaper Granma, more than 11,000 Cuban computer scientists will participate in the event, “the majority connected through videoconferences.” The quote is directed to sketch out a countrywide regulatory cyber-police continue reading

On February 19 and 20, around “260 specialists will share their opinions in commissions centered on four fundamental topics,” noted the Communist Party’s official media. The agenda includes “the human and scientific resources available in the country, electronic governance, cyber security, and economy and legality.” Throughout the Island, 21 headquarters will be made available for users interested in taking part in the debate and accessing the discussions. By visiting the website www.mincom.gob.cu, they will be able to share opinions and ask questions about the topics discussed, announced Ailyn Febles Estrada, Vice Dean of the University of Information Sciences of Cuba (UCI), on the web portal Cubadebate.

One of the most unique results of the event lies in the development of a new social organization that will group together the country’s ICTs (Information and Communications Technologies) professionals, into which recent graduates from diverse backgrounds like Information Technology, Computer Science, and Telecommunications could be incorporated. It is a clear attempt to centralize Cubans who have ICT knowledge, many of whom provide services in the private sector repairing computers and smartphones.

The implementation of a Chinese-style model, with a potent cyber police and extensive firewalls aimed at censuring content and filtering sites, is being outlined

The words cyber-security in the title of this article have also set off some alarms, since in recent years the government has augmented its ideological combat on the Internet. The implementation of a Chinese-style model, with a potent cyber-police and extensive firewalls aimed at censuring content and filtering sites, is being outlined as a priority for Cuban authorities.

The announcement of this workshop is added to the recent promise made by directives of Cuba’s Telecommunications Company (ETECSA) that 136 new “internet cafés” will be opened in the year’s first trimester. The majority of them will be found in the Joven Clubs de Computación (Youth Clubs for Computing), where users will pay for connection time in Cuban Pesos. On the close of 2014, 155 collective Internet cafés operated throughout the country, with a total of 573 available computers offering web access, a service that must be paid in Convertible Pesos.

According to the recently published report Freedom on the Net 2014, which analyzed 65 countries between May 2013 and May 2014, Cuba is the only country in Latin America designated “not free” in regards to Internet access. The study points out the limitations in accessing the world-wide-web as well as the censorship of certain webpages and the high prices for connecting from public places.

Translated by Fernando Fornis

Jose Varela, the Cuban Charlie Hebdo / Ivan Garcia

Ivan Garcia, Havana, 8 February 2015 — No one wants to know him except the readers of his blogs. Jose Varela is out there on his own. He is the type of humorist that public figures from both sides of the Florida Straits want to keep at a distance, the farther the better.

Ivan Garcia, Havana, 8 February 2015 — No one wants to know him except the readers of his blogs. Jose Varela is out there on his own. He is the type of humorist that public figures from both sides of the Florida Straits want to keep at a distance, the farther the better.

He is an outlaw squared. The Cuban regime has tried to co-opt his posts and cartoons when they ridicule dissidents. But when Varela trains his canons on the Palace of the Revolution, the curtain of censorship comes down.

Word has it he lives on a farm outside of Miami and that in 2006 — I do not know why — he broke into the offices of El Nuevo Herald, where he worked as a cartoonist, with a toy machine gun. continue reading

It was like a movie. News of the event made it all the way to Havana. “Pepe Varela got all hot and bothered. After a dirty trick by the Herald’s editors, he held the paper hostage. The riot police had to intervene. I love his blog. It’s irreverent and quite funny. On top of that, he writes well. That’s a lot to ask these days,” says a neighborhood friend who lives in Hialeah.

The first time I heard about Varela was in 2009. I had a blog on a website run by Yoani Sanchez called Voces Cubanas (Cuban Voices). One night someone mentioned that Varela had telephoned Sanchez asking if he could interview her or just meet her.

She turned him down. He was known to take pot shots at her in his posts (and still does). Some said he was with State Security, the perfect pretext in both Cuba and Miami for dismissing free thinkers and guys who are out there in left field.

I started reading his posts out of professional curiosity. They are written in the style typical of emails, without capital letters or proper punctuation. They are well-paced and entertaining, and anyone might end up being the target of his biting sarcasm.

For some time now a Google banner has warned visitors to his site that they are entering “enemy territory,” an affront to America’s vaunted freedom of speech.*

Neither the Inter American Press Association nor Reporters Without Borders nor any of the other high priests of press freedom has condemned this act of censorship by the U.S. search engine.

Varela could make a killing if he invoked the Fifth Amendment. Like it or not, he is an American citizen who pays his taxes.

It is quite understandable that a blog like his would be banned in Cuba. The country’s military rulers don’t have much of a sense of humor.

Political satire on the island is banned. In fact, the first press outlet to be banned — it happened in 1960 — was a weekly humor magazine: Zig Zag.

This reached an extreme in the 1980s when a cartoonist from the newspaper Granma was fired for showing a skull with a pirate’s hat in the middle of a photo of Fidel Castro. When the page was held up to the light, the overlay became visible.

It was probably a fatal coincidence that cost this man his job and several hours of interrogation by scowling counterintelligence officials.

In Cuba officials rarely smile, not even for the camera, but they are very adept at discerning insults or jokes considered “counter-revolutionary.”

Being a humorist in Cuba is an act of masochism. You have to craft jokes with double meanings if you want to escape the party’s guillotine.

The New Man that Che Guevara and Fidel Castro tried to create was a robot who killed yankees, planted bananas and worked as a volunteer without pay. Dancing to guaguanco, being unfaithful, reading novels and Corin Tellado and following major league baseball were petit bourgeois pursuits.

For a Cuban dissident to be considered a democrat, he presumably must defend freedom of expression and accept figures like Varela.

After the attack in Paris on the magazine Charlie Hebdo, the government and the opposition in Cuba denounced the savage murder of twelve people, including several of the publication’s cartoonists.

It was an empty gesture because neither the regime nor the dissidents tolerate criticism or jokes at their expense.

There is a Cuban Charlie Hebdo. His name is Jose Varela. He laughs at everyone. He lives on the other side of the pond and his weapon is his pen.

Translator’s note: In the U.S. a visit to the cartoonist’s blog site begins with a content warning that states, “Some readers of this blog have contacted Google because they believe this blog’s content is objectionable. In general, Google does not review nor do we endorse the content of this or any blog.” To enter the site, readers must then click a button that reads, “I understand and I wish to continue.”

Musings of a Blind Man (1) / Angel Santiesteban

Angel Santiesteban, 2 January 2015 — It finally happened, what a part of Cuban society desired and another share feared: Cuba and the United States resumed diplomatic relations. To criticize President Obama would be an innocuous, ungrateful, and useless, if we learned from José Martí that in politics what isn’t seen is bigger.

Angel Santiesteban, 2 January 2015 — It finally happened, what a part of Cuban society desired and another share feared: Cuba and the United States resumed diplomatic relations. To criticize President Obama would be an innocuous, ungrateful, and useless, if we learned from José Martí that in politics what isn’t seen is bigger.

Obama has charted a course and we have no option but to watch from the stands. that some remember that they gave him their vote isn’t elegant, especially because we must be grateful for the sheltering of several generations of Cubans. It’s a glaring mistake to think that Obama should defend the rights of Cubans when his only obligation is to guarantee the prosperity of the United States.

After having done that, he can — as he has done up to now — support the reality of Cubans: but the political, economic and strategic interests, at the presidential level, outweigh what a good part of we Cubans consider best for our nation. continue reading

We all know that the embargo was mild when compared — for example — with the sanctions applied to Russia right now. With the tiny totalitarian government of the Castros, we are now writing history, perhaps the worst since the Special Period, and where the only sustained human casualties were the most economically vulnerable Cubans unable to face the extreme hunger.

We might think that the United States never wanted to carry this guilt, because — needless to say — the leaders, their power structure and their minions, have not reached the rigor of that escalation that, ultimately, even the most extremist had criticized. On the other hand, it is not OK to demand constant turns of the screw to the impoverished Cuban economy when it is so distant and you know that you won’t experience even a single drop of the misery caused.

Most particularly, I continue against the lifting of the embargo, because — as I’ve said before — to the extent the dictatorship is strengthened, the arbitrary executions, illegal and abusive treatment against the dissidents. But to avoid our own suffering, more than is our usual share, we shouldn’t desire it for the rest of the population of the archipelago.

Now our minds are overwhelmed trying to unravel the intention of the American president. In the next post I will share my musings with respect to, where — perhaps — we could all be mistaken, because finding myself isolated I don’t hear what the specialist say on the topic. Perhaps what I consider an inconvenience, is an advantage, because the blind here the chords of the instrument better.

Ángel Santiesteban-Prats

Written in December 2014, Jaimanitas Coastguard Prison Unit, Havana

Posted in January 2015

Miami 2 / Silvia Corbelle

“It does not matter to return or not return” / 14ymedio, Yoani Sanchez

![]() 14ymedio, Yoani Sanchez, Havana-Barcelona, 17 February 2015 – During this year’s International Book Fair in Havana, Abilio Estevez’s novel, Los palacios distantes (Distant Palaces), was presented. Living in Barcelona for the last fifteen years, on this occasion the author brings us the story of Victorio, a character who shares his pains and passions.

14ymedio, Yoani Sanchez, Havana-Barcelona, 17 February 2015 – During this year’s International Book Fair in Havana, Abilio Estevez’s novel, Los palacios distantes (Distant Palaces), was presented. Living in Barcelona for the last fifteen years, on this occasion the author brings us the story of Victorio, a character who shares his pains and passions.

A few hours after the launch of the book in the Alejo Carpentier room, the novelist with a degree in Hispanic Language and Literature responded by email to some questions for the readers of 14ymedio, from Barcelona’s Gothic Quarter where he lives and creates.

14ymedio: To those who still haven’t read Los palacios… and hope to get a copy at the Book Fair, what would you like to warn them about before they enter your pages?

Estevez: Nothing, I would not warn them. I think should have its own importance, and the author should pass as unnoticed as possible. Also, the book should always be a mystery to solve, an adventure continue reading

“I’m not one who is going to close doors on himself.”

14ymedio: The novel was originally published by Tusquets Editores, in 2002. What was the process to achieve this Cuban edition?

Estevez: Yes, the Tusquets edition came out 13 years ago. Some time ago Alfredo Zalvidar wrote me kindly asking for permission to publish Los palacios distantes in the publishing house he directed, Ediciones Matanzas. I was very pleased. I told him yes, of course. I’m not one who is going to close doors on himself. I put him in contact with the rights office of Tusquests Editores, and that’s all I know. For the process on the Matanzas side you’ll have to ask Zalvidar.

14ymedio: Are you surprised that your book is being presented at an event where exiled writers are often excluded?

Estevez: Yes, a little surprised. Although Ediciones Matanzas has published José Kozer, Gastón Baquero… In any event, there is a lot in my country that doesn’t surprise me. Neither for the better nor the worse.

14ymedio: Laughter, dreams and hope slip into the life of Victorio, the protagonist of Los palacios… despite his living a reality that is falling to pieces, like his own house. How much of your own personal experience is in your story?

Estevez: Certainly there is a lot of my own experience such as, for example, Victorio’s homosexuality and the collapse of his house. However, I believe that it’s a mistake to confuse the character with the author. However much of me is in Victorio, it is also true that there are many other people and, as is natural, imagination. There is a moment in the novel, for example, when Victorio says he never knew love. A true friend, a night of confidences, said to me, “It has happened with me as with you.” “What happened to me?” I asked. Never having known love. I had to laugh. However confessional a novel may seem, it is no more than that, a novel.

14ymedio: How do you deal with distance when writing about a reality that you haven’t lived since two decades ago?

Estevez: I suppose this is difficult if you try to write precisely about a certain “reality.” I suppose it might have been difficult for Emile Zola or for Miguel de Carrion. But for me, I’m not interested in sociology disguised as fiction, something more than reality concerns me, isf we reduce the word to its sociopolitical connotations. I am not a “costumbrista” – a novelist of quaint manners. At least I don’t want to be one. And the world (and this is something that has to be discovered) is fortunately wide and strange, and the problems of human beings are alike and different in each place where one lives. The same distance as literary material. I don’t live this reality, but I live another that also wants to be narrated. Also, I always remember and quote that phrase of Nabokov’s in a wonderful interview, when he responded that everything he needed of Russia he carried with him.

14ymedio: What have you brought to your writing life in Barcelona? How much have you changed from the point of view of writing your experiences as an immigrant?

Estevez: Everything you experience brings something to literature if you are alert to it. Barcelona is a cultured and beautiful city. And I believe that the mere act of walking through the Gothic Quarter transforms the vision you might have about anything. With regards to exile, it seems to me an extraordinary experience, even if it is painful. When I was a child and they took me to church, I heard a prayer to the Virgin that at some point said something like, “To you we cry, the banished children of Eve.” And then I wondered, “Why banished? Banished from where?” I didn’t understand until much later, although my interpretation had nothing to do with religion, because I wasn’t religious. I remember a phrase of Elias Canetti: “Only in exile does one realize how much of the world has always been a world of outlaws.” It’s very good for a writer, this sensation of losing things, of knowing that you are not going to have them again.

14ymedio: Readers have followed and admired your work for years. Will we soon be able to enjoy a presentation of your novels where you will be physically present? Will you return to this Havana of “the distant palaces”?

Estevez: Thank you for the “followed and admired.” This question has no answer. I do not know. It does not matter to return or not return, because what I really want to return to is the good times that I lived. And that, to my knowledge, is impossible.

With a Capital C / Regina Coyula

Many prominent figures who consider themselves democrats enter into alliances — both tactical and strategic — as well as conversations with their political opponents based on dogma. One’s position on the embargo, as well as on renewed diplomatic relations with the United States, is a dividing line.

This aspect of our national experience is a result of our proximity to the United States as well as to a corresponding anti-imperialism in the extreme. It weakens the fight for democracy and serves as a political ploy continue reading

It is very disingenuous to use a sham referendum as a means of choosing an “eternal” social model, especially since its eternity has failed to produce positive results in any country in which it has been tested. In our own country it now has so many loopholes that one is hard pressed to demonstrate that we even live under socialism. This is even more difficult when the measures adopted to relieve the economic crisis rely on capitalist remedies.

It is also highly irresponsible to design a future for the regime’s heirs while locking out the nation’s voters. Let’s hope that — for reasons of dialectical sense and common sense — such a fate is, as much as possible, avoided.

We need an open discussion about how to protect and fully enforce human rights, stripping away the aura of malignancy and subjectivity with which the government portrays them and making them binding. Civil society must take a leading role in dealing with these challenges.

Rather than defining whether we are for or against the Embargo or diplomatic relations, it is ultimately a matter of whether we are for or against the Change.

11 February 2015

Coup warning? / 14ymedio, Gerver Torres

![]() 14ymedio, Gerber Torres, Caracas, 16 February 2015 — This article should appear today in the Venezuelan newspaper El Universal. It was censored. From here I make public my resignation as columnist for that newspaper, for which I worked for fifteen years.

14ymedio, Gerber Torres, Caracas, 16 February 2015 — This article should appear today in the Venezuelan newspaper El Universal. It was censored. From here I make public my resignation as columnist for that newspaper, for which I worked for fifteen years.

Maduro speaks daily with shock and anguish of conspiracies that he discovers, that he dismantles and that apparently reproduce themselves everywhere, all the time. Why does Maduro feel so tortured by a possible coup? The truth is that when one recognizes the circumstances surrounding him, one comes to the conclusion that Maduro is right and has many reasons to be distressed, to fear a coup, and even more continue reading

His international allies have abandoned him and are all in serious trouble: Cubans rushing to reestablish relations with the United States; Argentine president Cristina Kirchner at the end of her term with an economy in a tailspin and facing serious accusations of all kinds. Brazil’s president Dilma Rousseff, also with a stagnant economy and overwhelmed by the Petrobras corruption scandal, the biggest in the history of Brazil. Vladimir Putin, submerged in the Ukraine crisis, under sanctions by the European Union and in severe difficulties because of the fall in oil prices. Iran, negotiating a nuclear accord with the United States and trying to redefine its relations with that country.

Men very close to the regime are fleeing the country and starting to openly attack the regime: Leamsy Salazar defected to the United States with his wife to tell the story of the Cartel of the Suns (cocaine traffickers within the Venezuela military); Minister of Foreign Affairs Rafael Ramirez will sneak away, distancing himself from the regime. At any moment a bomb explodes there; Giordani reappears emboldened to say that the country has become the laughingstock of Latin America, just months after he was kicked out of the government.

The country’s employment is in the toilet, with Venezuelans experiencing totally unexpected events, lines, shortages, patients dying in hospitals for lack of supplies, runaway inflation, and other tragedies such as unchecked and unpunished crime.

Maduro can no longer count on abundant oil revenues and access to debt which could postpone the solution to many problems.

Maduro lives in a country institutionally ruined, turned into a jungle, without a Judiciary, devoured by corruption. Meanwhile all this was generated by the same regime that presides today and served to sustain it over a long period of time, this same lack of a framework of institutions that now turn against it. The regime no longer has anything to latch onto but repression.

Maduro knows that his popularity has fallen very low, not even the Chavez loyalists want him any more.

Maduro knows, and this is not small thing, that his eternal commander — Chavez — found justification for the 1992 coup in problems much smaller than the country has today.

How is Maduro not going to be anguished by the possibility of a coup?

The Filmmaker Ian Padrón Announces his Decision to Leave Cuba / 14ymedio

![]() 14ymedio, 16 February 2015 — The Cuban filmmaker Ian Padrón announced his decision to leave the island and stay in the US in an interview broadcast by CNN Mexico last week. The artist admitted that he, “was tired of fighting, of the complications,” on the island.

14ymedio, 16 February 2015 — The Cuban filmmaker Ian Padrón announced his decision to leave the island and stay in the US in an interview broadcast by CNN Mexico last week. The artist admitted that he, “was tired of fighting, of the complications,” on the island.

The son of film director Juan Padrón, in communication from Los Angeles, said that there must be respect for those who choose a life abroad and reiterated his will to change the situation in Cuba. “There has to be respect for the fact that I can think “differently,” but at the same time love my country. I feel that in many things I have been misunderstood, I have been marginalized, I have been censored many times on the island,” he said. “One has to be very brave to leave Cuba, but be brave also continue reading

The director of numerous videoclips, documentaries and the film Habanastation said he had postponed too long the decision too settle abroad and admitted that it would be difficult to start from scratch after having achived recognition in his own country. “I always wanted to live in Cuba I have come to the United States more than twenty times and have never decided to stay and live here. I felt a social duty, a responsibility to fight to improve my country.”

I sleep peacefully, whoever criticizes me, that’s their right, but I believe that no one is going to resolve my life for me. I have to resolve my life myself, I have to adapt myself and I have to fight for it,” he insisted.

The winner of the award for best video of the year at the latest edition of the Lucas Awards with the video Se bota a matar by the duo Buena Fe, criticized in the same ceremony the official censorship of two of his works (Control, with Juan Formell and los Van Van, and Soy, with Buena Fe), as well as the deficiencies in the process of choosing the winners.

M of Miami / Silvia Corbelle

Ángel Santiesteban: “I am a social reflection of my times” / Luis Felipe Rojas

Luis Felipe Rojas, 12 February 2015 — Just days after Ángel Santiesteban Prats sent this interview to Martí Noticias, he was transferred in an untimely manner to Villa Marista, the general barracks of Cuban State Security. However, his replies were already safeguarded, as was he.

This storyteller — who won the UNEAC (Cuban Writers and Artists Union) prize for his collection, Sueño de un día de verano (Dreams of a summer day, 1995), the 1999 César Galeano prize, the Casa de las Américas award of 2006 for his Dichosos los que lloran (Blessed are they who weep) — later started a blog where he set forth his ideas on human rights in Cuba, and he did not cease even unto imprisonment.

In 2013, Ángel won the International Franz Kafka “Novels from the Drawer Prize,” which convened in the Czech Republic, for the novel, The Summer When God Slept. Today he is responding to these questions from his improvised cell continue reading

Following is a Q&A between Luis Felipe Rojas and Ángel Santiesteban

Luis Felipe: At which moment did the narrator and character Ángel Santiesteban come to be?

Ángel: I can affirm that he came into existence at the end of the 1980s. I believe that the need to write, to communicate, to transmit my feelings, were a way of dealing, precisely, with the pain I felt inside of me. I recall that my first literary sensibility arose at the age of 17, when I found myself imprisoned at the La Cabaña fort, for the “offense” of having accompanied my family to the coast, with the intent of seeing them off, as it turned out.

They were later caught on the high seas, and I was charged with harboring fugitives — but on the day of the trial, the court ruled that, according to current laws, I could not be so charged, because between parents and children, and between siblings, such action was considered reasonable. However, I was prosecuted anyway because, according to the district attorney, I should have reported my relatives for clandestinely leaving the country, which is considered an act of treason against the totalitarian regime.

Notwithstanding, I remained in jail for 14 months. Thus I consider that before I was a writer, I was already one of my characters, which I used to share my personal pain with the other characters that, as of that time, I began to construct. In each character created by me, there is my pain, or that of my family, friends and neighbors. I am a social reflection of my times, and there is where my commitment lies: with myself, with my mother, with history and with my times, with no concern for the consequences that this posture might entail for me.

I suffer with every word I write, I bleed for every passage that I execute. I live and die with my characters; but always, I believe above all, it is through art that is genuine and uncompromised.

Luis Felipe: To what point were your narrative demons fused with your social intentions?

Ángel: I swear that this was not a goal, nor was it a commitment, and even less intended as a means to shock or gain attention. I believe, in fact, that this is not the way to achieve art. My creative seed took root in nonconformity and social fear — individuals who hid their antipathy to the political process and pretended, or pretend, to be sympathizers of the dictatorship — and this reflection of my times turned me into a voice, an alternative, and it was an unconscious process, because the foundation of my artistic vision is that which lacerates me, which strikes or preoccupies me, and then I want to capture it in the best way, according to the literary tools at my disposal.

When I discover a thought in a personal passage, or hear an evocative anecdote, a force is ignited in my being, and a different hunch alerts me that I should attempt it, and almost always this is tied to a social consequence.

Luis Felipe: You have assumed the tragic sense of life. Like Severo Sarduy, Guillermo Cabrera Infante or Reinaldo Arenas, you have assembled a literature that becomes condemnation. What does Ángel Santiesteban Prats process or write from within this enclosure?

The author of this interview with Ángel Santiesteban, 20 January, 2010, in Havana, Cuba.

Ángel: Above all, to recognize that with any artist to whom I am compared, among those three great Cuban writers, I am honored, and I appreciate the noble hereditary line in which you have placed me, because I will always recognize the distances between them and me. I respect them for their work and life, the suffering they hoisted like a flag, for choosing the emigration option, looking for those “three trapped tigers,”* who were them, for having been voices discordant with the political system.

I have experiences similar to Reinaldo Arenas, in terms of imprisonment and the cultural marginalization that he suffered; but I identify with all three in the matter of emigration — only that in their cases they had to displace themselves from the Archipelago, and in mine, I live those same consequences, but from the interior, inside the Island. For this reason, today I write about the reality that surrounds me, the injustice that I live.

I once wrote in a post that the last place that the dictatorship should have sent me was here, where I have had to develop myself as a human being, artist and dissident. I have written a book of stories out of pain, but which in my view and that of my friends, is still very raw, and I need to distance myself from the experience to revisit it and remove a political intention which, inevitably, is reflected in this collection of stories. I also wrote a strange novel, with a prison-life theme, which I intend to revise upon my release. I started a novel, Prizes and Punishments, of a more biographical cut.

My life experience is tragic. I have lived a tragic script that affects society, caused by the dictators’ political whims. It is known that “we writers nourish ourselves from human carrion,”** and this system is quite given to soiling us with the blood of its victims.

Luis Felipe: Your characters appear to be stricken with pain as if there were nothing else on the horizon. From whence this creation, these pieces of change contained in every story?

Ángel: At times it is, in a word, an image, or the reflection of an anxiety. When I perceive that someone is suffering, I feel a need to help him. I fervently believe that if a writer does not help to change — to heal — that reality, at least he has the duty to reflect it like a mirror of his times, as a social function. And, at times, we even seek alternatives to anemic responses for those sufferers, when they see in the characters their more immediate reality.

We have the possibility, as part of creation itself, to substitute, improve, provide, replace, exchange, our given destinies, and to create for ourselves something better. The variables can be many, to the extent of the writer’s capacity for talent and his artistic needs. I feel that I am the reflection of my times and so I try to capture this in my work.

Luis Felipe: If we refer to the backstory you provide in The Summer When God Slept, your novel is the reconstruction of an era. Describing life at sea, characters that are not precisely fishermen, the actual circumstances in which they decide to launch themselves to a new life, or to death, and the outcomes that come to pass from what we today know as the “Rafters Crisis,” what we have is a historical novel. What were your tools — were they historiography, sociology, or a thorough knowledge of those narrative techniques that you have been displaying for a long time?

Ángel: When I tackle a subject that I have not experienced, which is not even found in books that can be consulted, I begin a field study — in my case, depending on my subjects, with the soldiers who participated in the African wars, with the rafters who chose to return from the Guantánamo Naval Base, or marginalized characters who survive through crime.

I always make recordings of their narratives. In a few cases I had to turn off the recording equipment at the interviewee’s request, when they incriminated themselves in their testimonies and fear forced them into self-protection, upon revealing delicate matters — for example, terrible orders from a high-level military commander in Angola that produced innocent victims, or acts that they themselves committed and for which they are now ashamed.

I have the need, when I begin to treat a subject, to know every event — the history, the culture, the color of the earth, the scents, the vegetation — details that help me to transport myself and live in my imagination, to recreate, to go back in time and see, and feel, what I narrate.

The majority of the characters in my novel, The Summer…, are based on relatives or friends. Manolo is my younger sister’s husband. It is true that he was involved in the conflict in Africa, that he was a combat engineer, that he risked his life in the Florida Straits on a raft with other relatives, and that he later crossed the minefield [around the American naval base at Guantanamo] to return to Havana with his family.

In him, in that character, are composites of many characters. I interviewed every rafter I have met, producing hundreds of hours of cassette recordings — which is what I would use in the mid-90s — and in every one I captured the pain that burst from their words, gestures and silences.

Luis Felipe: There is a period of “painful apprenticeship,” as Carlos Alberto Montaner might say. Why are your stories loaded with victims?

Ángel: I am convinced that every Cuban who is a participant in the political processes — not only since 1959, but from before — is a victim of the whims, ambitions, and bad intentions of those leaders who have arrived at positions of power in the nation. In particular I base my view on the experience, the suffering, of the generations since that of my parents, through today, and I consider them victims of the regime.

And not just those who were opposed, but I also add those who were deceived, those who like my Uncle Pepe, bet on a better country, democratic and humanist, until they discovered that they had been deceived, but then no longer had the youth or courage to confront the deceivers — and they decided to take their own life out of shame at having been party to this miscreation that has governed for more than half a century, and has done so by executing, jailing and assassinating via its structures for repression and espionage.

Those who emigrate, those who remain inside the Island with their fears (even if only one); those who at some time have needed to pretend so as not to be reprimanded or punished; those who have lied, or are lying, and who betray their real thoughts and opinions about the reality that surrounds us — all are victims of the system.

I always reiterate that the only ambition I have had in life is to understand people — to understand them even if I don’t share their reasoning, but at least to know the cause, the feeling that they had at the moment of committing an act, be it positive or negative. I don’t always achieve this with human beings, but I do so with my characters. They must be transparent to me at the moment that I tell their story, understanding their actions, thinking and functioning.

I am a victim of my times, in the company of my characters, who reflect this human suffering.

Luis Felipe: It appears that you inhabit a space between the pieces of Carlos Montenegro and the lost souls of Reinaldo Arenas. The protagonists of your novel and stories move between the perdition of the night and the disillusionment of the days in Havana. Do you not fear that you will ultimately tell of a Havana that has been told and told again?

Ángel: Montenegro’s version is my personal experience, and we already know that reality surpasses us — it being so rich in hues, in multiple, inexhaustible tones that guarantee the health of that approach in the city and to the city. There is always a trace that hasn’t been covered, a new way of telling the same story, of sharing imperishable themes. Not even the same photo taken repeatedly in rapid succession can capture the same subject because its colors change constantly.

Yes, I fear repeating those paradigms of Cuban literature, but I do not believe that it can seem an imitation of those great and special writers, because there are many ways of seeing, ways of telling this Havana, this Cuba, at times so beloved, or so hated.

Ángel.

Border Patrol Prison Unit, Jaimanitas, Havana.

Translated by Alicia Barraqué Ellison

Translator’s Notes:

* A reference to the novel, “Three Trapped Tigers,” by Cuban writer Guillermo Cabrera Infante.

** Santiesteban is quoting Cuban writer Amir Valle, who made this statement during an interview with the journal, IberoAmericana, published in 2014. The original Spanish phrase, “Los escritores nos alimentamos de la carroña humana,” is used in the title of the article.

“It Is State Policy To Misinform People” / Cubanet, Roberto Jesus Quinones

Cubanet.org, Roberto Jesus Quinones Haces, Havana, 13 February 2015 — Raul Castro’s government, in spite of rapprochement between Cuba and the United States, continues the work of keeping people from freely accessing the internet.

Cubanet.org, Roberto Jesus Quinones Haces, Havana, 13 February 2015 — Raul Castro’s government, in spite of rapprochement between Cuba and the United States, continues the work of keeping people from freely accessing the internet.

On Monday, January 19 Cubanet published a report about the detention of the young Guantanemero Leinier Cruz Salfran on Saturday, January 17 by State Security agents. The reason? Leinier was gathering together a group of young people outside of the Hotel Marti, connecting through his laptop to the building’s WiFi and sharing the Internet with the others present who had also brought their portable computers to the location.

We contacted the young man who agreed to grant us this interview:

Q: Leinier, why did State Security detain you?

Because according to them I was committing a crime of Illicit Economic Activity.

Q: What did you do?

I shared the use of the Internet with other people through Hotel Marti’s wifi continue reading

Q: How many users came to connect to the Internet at the same time because of your initiative?

There was no fixed number, there were days when more than fifty people connected on the ground floor of the Hotel Marti which was generally where I was connected.

Q: What was the typical connection speed when everyone was connected at the same time?

The Hotel Marti has a bandwidth of 6 mbps (megabits per second) which equates to a download speed of 600 kb per second. The speed was sufficient for chatting, participating in a video conference or carrying out an audio session on Facebook. The speed was acceptable.

Later the hotel managers applied a speed limit of 2 mbps for each direct client. Only three people could connect directly to the hotel without interference. If another person connected the speed was divided among the four.

In the end, I had to tell the users that they could not do video conferences because now the bandwidth was insufficient for everyone. Everything was limited to opening pages, downloading email and voice sessions.

Q: How would you rate the internet connection opportunities that exist today in the city of Guantanamo?

There are very few internet access points, just two Internet rooms with 10 computers for a city of more than 150,000 residents. Furthermore, now the Hotel Marti denies Internet access to Cubans, who now cannot even pay a dollar to go up to the terrace which is where they have placed the wifi access.

Also, in the Hotel Guantanamo, the equipment for the point of access used to be in the lobby and now they put it on the second floor and even removed the antennas, which they only put up between 4 and 8 pm. Whoever wants to access the internet has to pay one dollar per hour. This part a decision by the government itself.

Q: The police accuse you of supposed illicit economic activity. Did you charge for sharing Internet access or did you share the cost of the connection with your friends?

I never charged because I knew they were following me. After I started sharing the connection I knew that I had become a dangerous enemy for the authorities and I knew that at some point I was going to confront them face to face, obviously on their terms, so I just shared the cost of the connection.

Q: Is there a law in Cuba that prohibits sharing the connection cost among several users?

I don’t know. During the interrogations they spoke to me of a crime called Violation of Contractual Services, something like that, in which the crime of violating a contract incurs a penalty of up to three years incarceration. Apparently they were convinced there was no evidence of any illicit economic activity, however, they emphasized that I violated the contract with ETECSA (Telecommunications Enterprise of Cuba) by using the Nauta (Internet) service, but in my opinion they did not want to go to the extreme of sentencing me.

Q: Did they return your laptop, flash drives and camera that they took during the search of your home?

No, they still have not told me what they will do with them. They took them from me and have left me disarmed because I am a programmer.

Q: Do you plan to do it again?

No, no I cannot trip on the same rock, it would be stupid if I did that. I think I have to focus my efforts on other artists, other projects that I have in mind until I find a person with strength and the chance of helping me carry them out.

Q: Why do you think they authorities hinder cheap Internet access for young Cubans?

I believe that it is the policy of the State to maintain massive disinformation for the Cuban population, and that is demonstrated by the fact that this government has never permitted free access to information. Here we have no chance of getting computers, mobile devices, access to satellite TV, the Internet, there are no satellite phone connections or access to information technology. What they have done to me proves it.

Q: What is your current legal situation?

Apparently I am not going to have a trial. They told the mother of my daughter who communicates with me to go to the Operations Unit to process the application of a fine, God knows for how many pesos, but I have decided not to go until such time as they communicate it to me as the law provides, through a document. The same way that they came with a search warrant the very day that they arrested me in front of my neighbors as if I were a delinquent and arrested me, that’s how they must do it for me to go there.

(We went to the Hotel Marti, the place where Leinier carried out his supposed derelict activity for which he was arrested. This reporter tried on three occasions to speak with the hotel manager, leaving his address and telephone number with a note in which we expressed that our intention was to bring to her attention what Cubanet published so that she could offer her viewpoint. In spite of our efforts, the lady did not agree to an interview.)

About the author

Roberto Jesus Quinones Haces

Born in the city of Cienfuegos September 20, 1957. He is a law graduate. In 1999 he was sentenced unfairly and illegally to eight years incarceration and since then has been prohibited from practicing as a lawyer. He has published poetry collections “The Flight of the Deer” (1995, Editorial Oriente), “Written from Jail” (2001, Ediciones Vitral), “The Sheepfolds of Dawn” (2008, Editorial Oriente), and “The Water of Life” (2008, Editorial El Mar y La Montana). He won the Stained Glass Grand Prize for Poetry in 2001 with his book “Written from Jail” as well as Special Mention and Special Recognition from the Nosside International Poetry Competition in 2006 and 2008, respectively. His poems appear in the 1994 UNEAC Anthology, in the 2006 Nosside Competition Anthology, and in décimas selections “This Jail of Pure Air” by Waldo Gonzalez in 2009.

Translated by MLK

Cubans of Milkless Coffee Put Their Feet on the Ground / Ivan Garcia

Ivan Garcia, Havana, 14 December 2015 — “The truce ended,” bawled a newspaper vendor on the bustling central Calzada de 10 de Octubre, in south Havana.

Ivan Garcia, Havana, 14 December 2015 — “The truce ended,” bawled a newspaper vendor on the bustling central Calzada de 10 de Octubre, in south Havana.

Leaning against a peeling wall in the lobby of an old neighborhood movie theater, the vendor offers the newspaper Juventud Rebelde (Rebel Youth) to passersby who read, while they walk, an article by the historian Elier Ramirez calling for Cubans to be cautious about the dark intentions of the United States.

At the door of a farmers market stained with reddish earth, and with stands overflowing with pineapples, sweet potatoes and yucas, Roman, a market clerk, reads continue reading

“It’s more of the same. They want to crush Cubans’ widespread expectations after the 17 December accords. The other day the newspaper Granma also was marking territory, saying that our sovereignty is not negotiable. Those people (the regime) are scared shitless. If the doors really open, the system is going down. It won’t last as long as an ice cube in the sun,” says Roman.

After noon, the old newspaper seller, sitting on a cardboard box in a doorway next to an art gallery, eating a serving of rice and beans and a slice of an omelet.

In a bag he still had more than thirty unsold newspapers. “We Cubans don’t care much about the news any more, good or bad. There are people who buy the newspaper to wrap up their garbage or to use as toilet paper. The enthusiasm awakened by the December 17th news has died down. They (those in the government) want it that way. And that’s why they’re saying the Yankees are the enemy and the people want to go to the US,” says the old vendor.

At El Lateral, a private restaurant on Acosta Avenue, a group of friends were drinking Cristal beer while waiting for their Hawaiian pizzas. They preferred to talk about soccer, Neymar, Cristiano Ronaldo or “The Flea” Messi.

The government’s political manipulation of the issue of relations with the United States. They haven’t written even a comma to implement some of the measures that could favor the owners of private businesses. They don’t want to leave the throne. They don’t want people to live their lives independently and to have a better standard of living. My advice: leave Cuba. The sooner the better,” says a boy with a quirky haircut.

In a park in the Havana neighborhood of Sevillano, Daniel, retired military, looks after his grandson riding a bicycle. “People aren’t happy with the Cuban government’s treatment of Obama’s policy toward Cuba. Most want the tensions to end. We’re tired of the same broken record. Cubans want to prosper,” he says, lighting a Popular brand cigarette.

“I wonder if the government thinks about the future. For the youngest people, the Cold War is ancient history. Our differences are not theirs. Cuban youth see the United States as an aesthetic reference and a model life,” says the ex soldier.

When asked about the issue of democracy and human rights, the silence is profound. “I don’t think you can pressure Raul Castro on that topic. That political rights aren’t respected in Cuba? It’s true. But the world, expect some dozen nations, in one way or another also violates human rights. You have to wait for this generation of leaders to die for there to be an opening in this land. The government has one last option: get on the train and normalize relations. If they don’t do it, it’s obvious to the people, who are already tired of everything,” says Daniel.

In an Internet surfing room in the old part of Havana, a twenty-something employee who sells mobile phone cars has her own therapy to escape the political.

“For my mental health, i don’t read the newspaper. I prefer to rent the “packets” with soap operas, serials and movies. My personal goal is short-term. Tonight I’m going out with a delicious “mango” (boy) who has a car and money, and enjoy a disco. It is my present and my future. In Cuba you can’t pick a fight. Otherwise those old guys (the Castros) will kill you with a heart attack,” she says laughing.

The good vibrations provoked among many ordinary Cubans by the news of December 17th is being displaced by the permanent indifference of the olive-green regime. The desire for a radical change that could transform their lives was just that: an illusion.

Photo from Cubanet

13 February 2015

Scientists Find a More Aggressive Variant of HIV in Cuba / 14ymedio

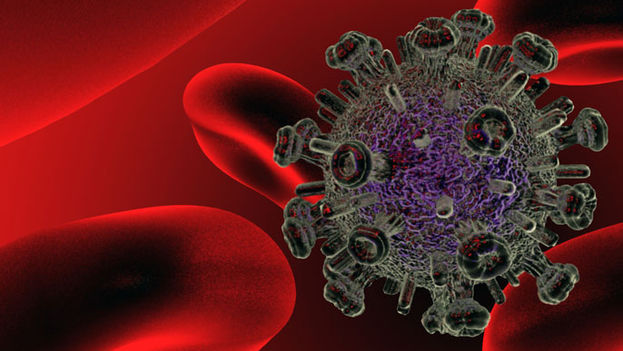

![]() 14ymedio, Havana, 13 February 2015 — A team of researchers from the Catholic University of Leuven (Belgium) and the Pedro Kouri Institute of Tropical Medicine in Havana have discovered a new strain of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) present on the island, according to a study published in the scientific journal scientific EBioMedicine. This variant, native to Africa, accelerates the time in which the infected person develops AIDS.

14ymedio, Havana, 13 February 2015 — A team of researchers from the Catholic University of Leuven (Belgium) and the Pedro Kouri Institute of Tropical Medicine in Havana have discovered a new strain of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) present on the island, according to a study published in the scientific journal scientific EBioMedicine. This variant, native to Africa, accelerates the time in which the infected person develops AIDS.

Through the monitoring of 95 patients who received treatment at the Havana institute since 2007, scientists detected that those infected with this strain showed a high amount of virus in their blood and progressed to AIDS at a much faster rate than average, the average being between 6 and 10 years. The study suggests that each year between 13% and 16% of patients diagnosed in Cuba already had AIDS at the time their infection was detected.

Each year between 13% and 16% of patients diagnosed in Cuba already had AIDS at the time their infection was detected

Scientists relate the rapid development of AIDS in Cuba to other factors as well, such as a low use of condoms, often unavailable in the pharmacies, and other diseases such as oral candidiasis.

In Cuba, 19,781 new cases of HIV infections were diagnosed between 1986 and 2014, according to a report by the Island’s government.

Shortage of Condoms / 14ymedio, Rosa Lopez

![]() 14ymedio, ROSA LOPEZ, Pinar del Rio, 12 February 2015 – People in Pinar del Rio didn’t have to wait to read about it in the newspaper Granma. For weeks the popular voice says it, louder and louder. “There are no condoms,” started to be heard like a whisper on the corners. “There are no condoms,” said the couples on hearing it and the teens warned their parents before they went out on Saturday night. “There are no condoms,” howl the pharmacy clerks when their customers dare to ask. The uproar was such that finally this Wednesday the official organ of Communist Party issued a formal answer.

14ymedio, ROSA LOPEZ, Pinar del Rio, 12 February 2015 – People in Pinar del Rio didn’t have to wait to read about it in the newspaper Granma. For weeks the popular voice says it, louder and louder. “There are no condoms,” started to be heard like a whisper on the corners. “There are no condoms,” said the couples on hearing it and the teens warned their parents before they went out on Saturday night. “There are no condoms,” howl the pharmacy clerks when their customers dare to ask. The uproar was such that finally this Wednesday the official organ of Communist Party issued a formal answer.

Those who still have a sense of humor, after a month long shortage continue reading

Before every shortage, some specialist always suggests a workaround. That’s what happened with the article published by the official newspaper, which says that the Program of Prevention and Control of STDs and HIV proposes that, given the scarcity of the product, “people find alternatives, for example, limiting the sexual act to kissing, caresses and masturbation…” Tell that to a customer burning with passion whose store of condoms ran out at the end of last year!

What the note in Granma doesn’t say is that contraceptives aren’t the only thing missing from pharmacies. A brief tour this morning of places where medications are sold in the city of Pinar del Rio demonstrated that other products have also been disappearing for weeks. Both in the pharmacy on the central corner or Marti Street at Recreo, as well as the one known as Camancho or the one located on the ground floor of the 12 story building on Maceo street, have empty shelves and drawers.

The shortages include drugs such as Meprobamate, anti-flu medications, Dipyrone, Azithromycin, Prednisolone and Clotrimazole. What do the public health authorities propose in the face of such shortages? Looking for alternatives like with condoms? Will they then engage in the fantasy to anticipate what the patients should do in the face of such shortages.