“Fear is ridiculous and it provides ammunition to the enemies of liberty.”- The Venerable Father Felix Varela

We would like to thank you with utmost respect and kindness for taking time to read this letter.

We are Cuban Catholic youth who everyday are intent to fortify ourselves to the clamors that burst forth and splatter our conscience from the brutal reality of our beloved Cuba. From the dawn of our youth we have occupied the rows of the Christian Liberation Movement (MCL), a pacifist-civic movement which, inspired by Christian humanism and the principles of the Social Doctrine of the Church, has yearned for the freedom that Cuba has wanted and needed for more than 25 years.

We love the church, and we have grown under her auspices with the influence of her Ignatian spirituality. Because of this, we turn to you to voice our pain and concern with several Cuban Bishops who, surrounded by pro-government Cuban laity and other figures of privilege, pronounce and act in the name of the Church before the unfolding drama that we Cubans have lived in for more than half a century.

Increasingly, ecclesial offices are shunted into a caricature of the masses, to be only the bottom substrate in the background and a common denominator legitimizing the government, asking for more votes of confidence for the politico-military junta who govern as dictators and awaiting a new “leader” to succeed the dynasty of the Castro Brothers and amend the “justified errors” of 55 years of governmental mismanagement that devastated a country whilst omitting the daily violations of human rights and the repressive despotic and unpunished actions of State Security personnel against nonviolent opposition and begging for weak reforms which lack transparency and in so doing be able to navigate comfortably in all waters through the use of ambiguous and confusing language that decorate and embellish the harsh realities, foregoing calling them by name, and thus presenting themselves as authentic rhetoricians and builders of bridges. continue reading

Perhaps we should remind our pastors how both dialogue and mediation necessitate a clear sense of identity and an indispensable autonomy to be able to express it, without circumlocution, in the collegial search for truth amongst peers and the commencement and recognition of all the parts, with an adequate dose of moderation, but while maintaining transparency, rigor, and respect for the truth. And this, in a cystic dictatorship with more than five decades of authoritarianism, carries a price and only those who have overcome, from a detachment of having nothing to protect and nothing to aspire,the fears that have impeded their inner liberty strive for progress.

Those of us who know from within the realities of the Church of Cuba understand that the courts of Havana’s Apostolic Palace is an interplay of political factors and that the exclusionary practices of the Church, whose byzantine politics are without morals and constancy, stretching and pulling, consisting of ambiguities and flatteries, and, in the worst form of diplomacy, sacrificing the integrity of the simple and naked truth expressed with the sole presupposition of due respect to substitute it in favor of strained praise, finally allowing itself a shallow criticism and in doing so maintaining the status quo, has the seal of the illustrious cardinal that occupies its halls. This shackle to the same apprehensions, pressures, blackmail, compromises, limitations, protection of self-interest and tacit or explicit agreements, that mark it’s actual relation to the State, and who for decades has been its helmsman, is Cardinal Ortega.

Subjugated to the fluctuations of this complex relationship, the precarious autonomy of Catholic publications and centers for the formation of laity and the devoted, has exceeded the bounds and good-willed intentions of its founders and has shifted into the propaganda of, no longer the Archbishop, but whomever holds the upper hand in said relationships; those who allow them to continue to exist and in circulation so long as they don’t overstep the threshold of tolerance or who ultimately fail to serve their vile purposes. The choice is clear: either they alienate themselves from reality marking socio-political themes as taboo, in a country where nothing is apolitical, on the contrary everything is profoundly politicized and ideologized, or claim the input of a fraud-exchange thrusted by the government.

What do they try to convince us of now? It was Raul Castro himself who speaks of his own reforms claiming that they are for more Socialism; we Cubans know all too well what that means. Regardless, has someone asked us, like citizens, if what we want in today’s age is more Socialism? And what Socialism? How do they want to convince us, the Cubans who live both here and abroad suffering exclusions and disadvantages,that they are advancing towards the implementation of laws that will permit us to reencounter ourselves with how we wish to be? That this framework of oppression, without rights or transparency, is the path of transition? What does this transition consist of?

Graduality only makes sense if there is a transparent perspective for our liberties and rights. Don’t continue to speak on our behalf; we would have our own voice raised and heard. It’s not enough for Cuba to open herself to the world and the world unto Cuba: first Cuba must open herself to Cubans. To come to accords with our own officials, like several democratic governments and institutions have done without caring that they don’t represent the Cuban people, is to perpetuate oppression.

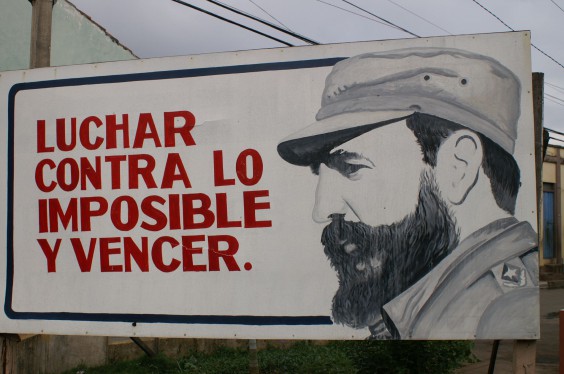

Enough of deciding and thinking on my behalf and imposing an ideology of the State that doesn’t represent me. Enough of obligating me to collaborate in a political farce that overshadows my principles and the conditions of a free man, under the threat of losing it all: education, job, sometimes family and friends, liberty also and even life itself. That is why fear is the guiding principle of this society, fear and lies, sustaining a society of masks and simulations during decades of weak men, evasive, possessing only half-truths, incapable of facing and naming that evil which corrodes us within. That is how we Cubans live.

We wish that the Church, a pilgrim in Cuba, would dare to throw out the merchants from the temple, those who in the virtue of secret pacts do away with the worth of a human before the importance of abstract numbers. We yearn for a church who would not accept as privilege that which is her rightly due in exchange for her silence.

A church, with whose prophetic voice and testimony of life in truth in a society rotting with fear and lies, can share the cross of the ineffable, solitude, humility, deprivation, calumny and persecution that we suffer, we who have broken with the vice of self-deception that has become our collective dementia.

A church that does not please itself with having its pew saturated with comfortable mediocrity, dragging the multitudes behind images that don’t save and only awaken shallow devotions while the most precious component of her identity is diluted and watered down in a pseudo-religion of the masses, recovering spaces and buildings for the mission, and then relying heavily on human means to, with God and the splendor of His message being considered too subversive against the established order, advertise a private pseudo-gospel of moral and social content more “enlightening” for our people.

A church that stirs those consciences paralyzed by fear and custom before the face of irrationality, disfunctionality, and the absurd demands of a long-lived absolute and arbitrary regime by inviting each man and woman to contemplate themselves in the reflection of the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. A church, who once again noting the worth of the poor, the few, the small, the gradual, the weak, the anonymous, offers in her small but Christian and arduous communities something incredibly different and powerfully captivating, and no longer the swarms of vitiated environments.

That church, incarnated and undivided, has been present for years in the figures of brave and exceptional bishops, innumerable priest, religious and missionaries many of whom we have seen depart in pain: banished, dismissed by bishops and superiors, or voluntarily resigning before submitting to perverted or perverting regulations.

It is that diminishing church constantly in danger of becoming extinct, that has produced genuine miracles thanks to the those youth and families who everyday make the conscious decision to remain, assuming upon themselves the dangers and hardships, every day resisting the temptation to join the mass exodus of a people who stampedes fleeing to whichever place where they can construct a more dignified life, hold an honorable job, know the taste of liberty, fight for their dreams, aspire to prosperity and happiness.

That church revealed with her very life and not only through discourse, the profound realities of our faith: the Incarnation, Calvary, Easter, the Resurrection. In her, we cautiously aimed to really be priests, prophets and kings. Because it is in that church that we learned to search and wish for the will of God as our most precious treasure, today we still dare to swim upstream, muting the warnings of close friends occasionally whispered in the temples and sacristy from those who speak in the name of God, and even the anguished cries of our mothers who implore us to renounce, run, escape and forever occupy ourselves with our own well-being and our families with thousands of unanswerable arguments from plain pragmatism of calculated deeds and force or consisting of acrobatic tricks with alleged reasons of faith that end fading away at the feet of the Crucified.

Because that church has taught us to believe against all the evidence and to hope against all hope, our lives today continue to be an answer to the questions and call of God: Where are those responsible? Strengthening us to continue being a voice in the desert, a light in the darkness and an omen of hope in the midst of the apparent sterility in spite of the burdens and fatigue. Because Cubans need the help of Jesus on the Cross to be able to look with love upon these last 50 years that has oppressed physically and psychologically and to dare to shout NO MORE!

We Cubans need a church that will aid us in overcoming fear. Fear is the origin of lethargy and hopelessness that overwhelms youths and society as a whole. We need a church that will help us in these first steps toward Liberation, the first steps that always start with an individual and en as a roaring shout, stronger than oneself and that must be shared.

An advocate church must be a place of liberty, where reconciliation does not convert itself to historic amnesia disguised as the goodness of the righteous. It has to be a place of freedom of expression, not in attempts politicizing the temple, but instead to create the language which will be able to articulate our story from the bottom up, omitting the “victorious” figures who attempt to reconstruct history. We need a Mother Church, who works for the truth without ambiguities, who doesn’t confuse love for one’s neighbor with political opportunism. A church that will help us name this unnameable pain so that we may offer it up and act, without our voice being silenced.

Count on us Holy Father! God bless you and keep you!

A big hug from the Caribbean,

Erick Alvarez Gil, age 28, Telecommunications and Electrical Engineer, San Francisco de Paula Parish.

Anabel Alpizar Ravelo, age 29, Bachelor’s in Social Communication, dismissed from her job, Chapel Jesus Maria

Luis Alberto Mariño Fernández, age 27, Bachelor’s in Music Composition, Salvador del Mundo Parish.

Maria de Lourdes Mariño Fernández, age 29, Bachelor’s in Art History, Salvador del Mundo Parish.

Manuel Robles Villamarin, age 24, Information Tech, expelled from University, Siervas de Maria Parish.

Translated by: Joel Olguin

3 August 2014