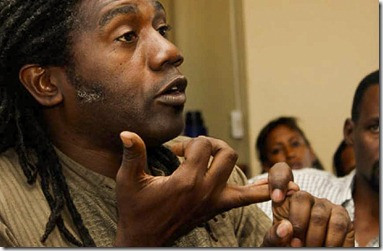

Interview with Dimas Castellanos Marti, historian and journalist.

From Havana, Felix Sautie Mederos

“Unravel the causes of the crisis our society finds itself in (…) The concept of race as a group of hereditary characteristics seems to lack foundation, as a social construction it has a damaging effect on human dignity (…) In 1959, the democratic, popular Revolution inflicted the hardest blow in the history of Cuban racism (…) Then, racism, expelled by law, took refuge in the mind waiting for better times (…)” A pending challenge…

Dimas Cecilio Castellanos Marti is a name that’s repeated in digital spaces, on account of his articles which refer to current problems that impede the development of Cuba and the quest for historical clues that have influenced its emergence and evolution. Like all people who write and publish their ideas, he has won friends and also detractors. There are even some who discredit and try to silence him, considering him in the camp of the enemy. These dogmatic perceptions have been caused by many divisions of Cubans, including between those in favor of social justice and distributive equality. These are practices we have to eradicate and give a real 180 turn to these narrow minds that contribute little to the development and future and become a very significant indicator of the necessity to achieve the changing of minds that President Raul Castro has reiterated so often. Perhaps it is because they don’t dare to debate with him about his opinions or because they opt for the easiest way to stay out of problems with what one could call “the established.”

It’s precisely in honor of this change of mind that I’m interviewing friend Dimas, with the goal of making explicit his life and his opinions without exception of any kind; I believe it interesting to express the thoughts of this author who, despite being excluded by some, stays strong in his progressive opinions in favor of peace, liberty, distributive equity and social justice. I have had the opportunity to know him closely, we have been together in Christian efforts and in theological and Bible study. I am a witness to his exceptional, unwavering closeness to Christianity.

I consider his research, his origin and his intellectual development worthy of divulging, even more so because of the significance that they have acquired due to the motive of the recent debate over the article published by the Cuban intellectual Roberto Zurbano in The New York Times with the controversial title, “For Blacks in Cuba, the Revolution hasn’t Begun,” which, according to its author, was a distortion of the original title he sent to the New York paper: “For Blacks in Cuba, the Revolution hasn’t Ended.”

Felix Sautie: I understand that you were a member of the Socialist Youth in the former province of Oriente and that you participated in the 8th Assembly of the Popular Socialist Party at the triumph of the Revolution. Is that true?

Dimas Castellanos: Yes, that happened. I served in the Socialist Youth (JS), the youth organization of the Popular Socialist Party (PSP). I was Secretary of my Base Committee, President of this organization in the municipality of Bayamo and Delegate at its last congress. In 1960 I entered the ranks of the PSP, where I served until its dissolution in 1962. It’s true that I participated in the 8th Assembly of PSP, celebrated in August of 1960, but not as a Delegate. It just so happened that when this event was celebrated I was in the PSP National School for Leaders and it was decided that the students would participate in some sessions that were being celebrated in the Comodoro Hotel, very near where the school was located. In this Assembly, which was the last of the PSP, they approved the thesis: “Defend the Revolution and advance it,” which meant propel the democratic, popular revolution to socialism and communism, which were the objectives of the Communist Party of that time.

FS: How did you happen to join this Communist militancy and what has been your evolution since then up till now?

Dimas Castellanos: My joining the communist militancy had family and class roots. My father, a tobacconist, was a member of the PSP. He worked in our house along with 7 or 8 other cigar rollers. From a young age I heard conversations about politics, culture, science and other subjects; something characteristic of this trade that permits talk and debate without interrupting production, which explains the high cultural training that workers in this sector had. Also, though with less intensity, this happened in the typography trade, in which I worked as an apprentice in various print shops that existed in Bayamo. In this cultural environment, along with the civics education from public school, my socialist ideas of liberty and social justice hatched and my vocation for politics, history and pedagogy developed. continue reading

As for my evolution I can tell you that in 1956, when the landing of the yacht Granma happened, I was only 14 years old, but I already had a considerable political consciousness. For that reason I linked with the Socialist Youth and joined the PSP. Later, in October of 1960, when the JS, together with the youth organizations of the Revolutionary Directorate March 13 and the Movement July 26, integrated into the Association of Rebel Youth (AJR), I was designated as president in Bayamo. Following that, I held various positions in various municipalities and in the provincial management, both in AJR and in the Union of Communist Youth (UJC), until July of 1962.

From that moment until today, my ideas have evolved from the constant incorporation of new knowledge, from an open mind, from the busy political responsibilities, from participation in conferences and other events, from events I experiences around Real Socialism during my stay in Russia, from my studies in Political Science, from my participation in the Youth Centennial Column in the Cuban Military Mission in Ethiopia. All of that, along with my constant reading has permitted me to develop a critical analysis of the progress of the revolutionary process. Even though my socialist ideas (social justice and liberty) are the same, I understood the impossibility of constructing a socialist society on the back of civil liberties. For me, socialism cannot exist unless it’s democratic, which is impossible given the total control of the State over society.

FS: You were a worker starting from a young age, I believe a welder and you had many jobs, but currently you’re at the university level, you have been a university professor and you have a very active intellectual life. Do you want to explain to our readers of Por Esto! this cultural evolution, what are you doing now?

Dimas Castellanos: I started working as a boy, first helping my mother in the selling of clothes in rural areas, in being a distributor of fresh milk, in a workshop that made fine-cut tobacco, selling sweets and eggs in the streets, etc. Later, from age 11 on I worked in various shops as an apprentice of typography, blacksmiths, and welding, which was my final trade. Precisely because I was a welder, when I left work in the management in UJC, the Commander Joel Iglesas, Secretary General of this organization with whom I had a magnificent relationship, started me in a work position in the construction of the Renté Thermoelectric plant. Later I moved, within the same position, to the construction of buildings in the Jose Marti District, also in Santiago de Cuba.

Due to my working life, during my childhood I studied irregularly until the 5th grade of education. Being in Renté, now 21 years of age, I took an educational test in which I scored as 4th grade and from that level I restarted my studies, always on the night shift. With the help of a private teacher (Ana Parodi Dominguez) I reached the 6th grade in 2 months and in 1964 I enrolled in Secundaria Obrera (Secondary Adult Basic Education)–one year in duration– and I entered into the Facultad Obrera Campesina (Higher Level Adult Basic Education) that functioned as an annex of the University of Oriente, where in two and a half years I reached a level “equivalent” to a pre-college student. In 1967 I was selected to study metallurgy in Russia, since at that time the Government of Cuba had the goal of converting the Island into a metallurgy power. I stayed for 2 years in that country, but my basic accelerated training turned out to be insufficient to complete the studies: I had spent less that four years from 4th grade to 12th grade. On my return to Cuba I spent six months in the Youth Centennial Column and in 1971 I enrolled in Political Science, where I was second in my class and I graduated with a Bachelor’s degree. While waiting for my diploma, because of my condition as Student Aid in Social Psychology, I was allowed to simultaneously take various courses in the School of Psychology at the University of Havana, which helped me develop a much more holistic formation.

Once I graduated I started to work as a professor of Marxist Philosophy in the Agricultural Department of the University of Havana (which became the Superior Institute of Agriculture and Livestock of Havana in 1976), where, for not circumscribing myself to the schematism that was demanded in the teaching of this subject and for not being a member of the Communist Party, I was fired from teaching, despite the excellent evaluations I had obtained. Following that I relocated as a technician of Information Science, I enrolled in various post-graduate courses and joined my philosophical knowledge with this activity, which they told me was “the philosophy of information.” In 1992 because of my socialist democrat ideas, I was excluded from the Ministry of Higher Education.

Currently, as an amateur historian, I dedicate myself to researching and writing about the relations between the Cuban predicament of today and the preceding history. I publish the results in El Blog de Dimas and in various alternative digital publications. I occupy myself with this activity, now that I consider that after having participated in the revolutionary process, having evolved culturally and politically and having an understanding of the role of history in the unfolding of social processes, I can’t do anything but help, from inside my country, to unravel the causes of the crisis which our society finds itself in.

FS: The disciplines that you have studied include Biblical studies and theology. What concepts do you have of spirituality and religious faith? How do you place yourself in these dimensions of life?

Dimas Castellanos: In the year 2001, 26 years after finishing my bachelor’s degree in Political Science, I enrolled in the Institute of Biblical Studies and Theology (ISEBIT), where I graduated in 2006. My interest in the study of theology came from lived spiritual experiences that didn’t have an explanation within the Marxist Theory. I was baptized and joined the Movement of Christian Workers. Once I familiarized myself with the essence of the Christian ideas I understood their relation with social justice, liberties and politics, which because of their impact on the destiny of people and people could not be far from Christ. For this reason, I incorporated spirituality and religious faith into my world view. If one of the manifestations of politics is the fulfillment of needs, or as some like to express it, the art of making the necessary possible, without a doubt Jesus practiced politics. The debate then moves to explaining the peculiar form in which he did it. If Jesus was, or was not, a revolutionary.

Revolution is one way to change reality, which overflows with social injustices, but always independent of the form it which it arises, it consists of an intent at an extreme solution which becomes active when legal and/or moderate attempts fail and imposes a radical modification of the existing situation. The fact is that, by the use of violence, in revolutions it is always imposed on the most capable at work, as irrefutable demonstrated in universal history.

This form of fighting for justice is different from the teachings of Jesus, for whom forgiveness was a cornerstone. Thus, between the revolutionary form of hoping to reach a “shining world” and the ways employed by Jesus Christ to reach the Kingdom of God, they only agree on the declared objective in favor of justice and the happiness of human beings. From there they move apart, since forgiveness, love, peace and conviction are the characteristic foundations of the Christian doctrine. So Jesus was not a stranger to the political dimension in which I placed my life. More precisely, my adhesion to Christian ideas of ethics and social justice along with my vocation for history has considerably influenced the study of the founders of the Cuban nationality, starting with the Father Felix Varela.

FS: Then what importance do you give studies of history and their use in political and economic analysis?

Dimas Castellanos: All presents have their keys in the past, history becomes an indispensable source and an essential tool for the understanding of social phenomenon. Men can accelerate or retard the progress of history, but they cannot stop it. In Cuba, after 1959, they tried to attribute an eternal character to a temporary event, which drove the postponement of the constant transformations that all societies demand. Today, in breaking the stagnation for diverse causes, the country is seeing the obligation to correct the wrong path. A task which surpasses any man, group, party, or institution and requires, therefore, the participation of everyone and a structural, systemic focus in tune with the crisis in which we are immersed, where historiography–analysis and interpretation of historical events–has a hugely important role to play; since it becomes very difficult, if not impossible, to find viable ways out of our problems without taking into account the ideas contained in the civic, political, economic, cultural and scientific thinking of illustrious Cubans who came before us. This passion for history is reflected in each opinion I present and in all the articles and essays that I write.

FS: I have had the opportunity to read some of your work on the problem of blacks in Cuba and we have sometimes discussed that subject. In this line of thinking, I’d like to ask you some questions that I consider to be important.

First of all: Really after everything the Revolution of 1959 has achieved to this date, are there still racial problems that affect the life and social development of the Cuban black and mulatto population? And if this is true, could you give a brief outline on the subject?

Dimas Castellanos: Yes, racial problems continue. The concept of race as a group of hereditary characteristics lacks foundation, as a social construction it has a damaging effect on human dignity. In Cuba it’s about a complex phenomenon intertwined with our economic, sociological, and cultural history which is reproduced in time. In this sense I advance in the form of a thesis, some of the aspects and key moments:

Black Africans appeared on the Cuban scene in the beginning of the 16th century, but it was towards the end of the 18th century that their massive entrance transformed the ethnic composition of the population, the geography, the history, the culture and the social structure of the country.

Not being the owners of their own bodies and subjected to inhumane living conditions, blacks responded by rebelling: the cimarronería [1], the apalencamientos [2], and staged uprisings. Through these rebellions blacks almost single-handedly wrote a chapter of our national history.

Faced with total inequality with respect to whites, blacks became creole, but in a different way from white creoles, which, to paraphrase Jorge Manach, precluded their a putting common goal above of their distinguishing features.

During the 10 Years’ War, begun in 1868, land-owning whites aspired to economic and political liberty while blacks aspired to the abolition of slavery. The simultaneous existence of these goals — independence and abolition — constituted the starting point for the formation of a national consciousness in a context where inequality and racial discrimination acted in opposing directions. This war, though it ended without fully achieving its objective, dealt a blow to the institution of slavery by liberating slaves who had participated in battle during the war and legally endorsed some liberties (contained in the Zanjon Convention), which gave birth to Cuban civil society.

In the interim between the 10 Years’ War and the start of the War of 1895, Juan Gualberto Gomez — supported by the colonial resolutions that limited exclusion from service due to race — introduced various principles similar to those that Martin Luther King would use six decades later in the civil rights struggle of American blacks and founded the Directorio Central de Sociedades de Color. From his position as a social activist he mobilized thousands of blacks to resistance. Facing arduous incidents while adhering to the law, he won access to spaces and facilities such as balcony and orchestra seats in theaters as well as to public classrooms, which until then had been limited to white children.

At the re-initiation of the war of independence, when slavery had already been abolished, blacks were newly incorporated, this time with an agenda of social equality. As before, due to their expertise in the use of machetes and living in the jungle, equality and solidarity between black and white fighters overcame racial prejudice.

With the coming of the Republic, where these skills were useless, a sociological program aimed at reducing the economic and cultural gap between whites and blacks was lacking. That lack was reflected in public office, in commerce, banks, insurance agencies, communications, transportation, tobacco stores and even the armed forces, which replaced the Liberation Army was made up mostly of whites, in a country where the 60% of the fighters for independence had been black.

The constant frustrations in the early republican years led to the founding of the Independent Party of Color in 1908 and the armed uprising of its members in May 1912. This last action ended with the most horrible crime committed in our history, because in addition to the thousands of blacks who were killed, killing happened between white-skinned Cubans against black-skinned Cubans, once again hindering the unfinished process of a common identity and destiny.

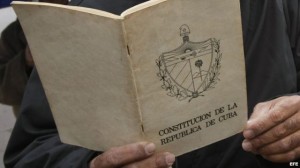

In the 1930s, various press organs, radio stations and leading figures in Cuban politics and culture engaged in a public debate against racism, thereby aiding the integration and social and cultural development of blacks, and as a result, strengthening the awareness of a common destiny. One of the results was the inclusion, in the 1940 Constitution, of a legal principle essential to the promotion of equality between blacks and whites, that stated, “all discrimination on the basis of race, color or class or any other cause harmful to human dignity is illegal and punishable.” However, this beginning was left incomplete in the never enacted complementary criminal law against discrimination.

In 1959, the Democratic and Popular Revolution dealt the most serious blow to Cuban racism throughout its history. However, with the dismantling of the existing civil society, in addition to its benefits also lost were the civic instruments and spaces that had contributed to the progress made so far. The mistake was to believe that racial discrimination existed as a result of social classes, so that once these were eliminated, they proceeded to announce its end in Cuba. Such a significant “achievement” led to the decision to remove the subject from public debate. Thus, racism, expelled by law, took refuge in people’s minds, waiting for better times.

Nevertheless the equality of rights among blacks and whites proclaimed by law had a weak spot: inequality that had been inherited and left unresolved. In other words the starting point, seemingly the same for both blacks and whites, put the former at a serious disadvantage. This explains why universities that had been primarily black and mulatto re-acquired their previous racial profile over time. Why was this? Among the reasons were that black families, with rare exceptions, could not give their descendents’ studies the importance they required given their own backgrounds. (I remember my father, the grandson of a slave, telling my mother, “Leave him be! He will study when he is big.”) In other words the familial support so necessary to success was missing, which facilitated a return to the former status quo.

Even during the very real crisis Cuban socialism experienced in 1989, blacks did not emigrate for well-known historical reasons and missed out on the much-anticipated cash remittances from relatives overseas. Evidence of this can be seen in the re-appearance of social inequities, in the high proportion of blacks in prison, in their significant presence during the mass exodus of 1994, in their concentration in poor, marginalized neighborhoods and subsequently in the re-emergence of discrimination.

In short, throughout our history racism was not treated in the comprehensive way that such a complex phenomenon requires, as consequence it continues into the present in our society, through half a century of revolutionary power. The most recent proof of the debate is about the black intellectual Roberto Zurbano, director of the Editorial Fund of Casa de las Americas, suspended from this responsibility because of his article which The New York Times published under the headline “For Black in Cuba, the Revolution Hasn’t Begun,” even though in an interview, he clarified that the original title was really that the revolution “hadn’t ended,” but reaffirmed his ideas that “on racism there is still much to discuss.”

In this polemic there are two distinguishing aspects: one, whether racism is present in Cuba or no; the other, the treatment of the subject given by Zurbano’s critics.

Regarding the former, exactly related to the theories presented, I will only refer to the two basic questions posed by Zurbano:

The economic difference created two contrasting realities that persist today. The first is that of the white Cubans, who have mobilized their resources to enter into a new economy driven by the market and to reap the benefits of a kind of socialism that is supposedly more open. The other is the plurality of the blacks, which is witness to the death of utopian socialism.

This statement confirms the similarity between the situation between the blacks higher up in the Republic, lacking economic means and instruction, and the lack of positioning today, to participate under conditions of equality when faced with the measures of economic liberty that are being dictated. One fact that reveals the reproduction of the causes, one of the sources of Cuban’s participation are foreign shipments, before which blacks are at a total disadvantage. Therefore, dark-skinned Cubans continue to be unequal from the start.

Racism has been hidden and has been reinforced in Cuba in part because it is not talked about. The Government has not permitted racial prejudices to be debated or confronted either politically or culturally. Instead, they frequently pretend that it doesn’t exist.

Here lies another key to the continuation of racism. They suspended debate on the subject and now, 54 years later, it’s not only uncomfortable to accept it, but a few of the intellectuals who have attacked Zurbano even go so far as to deny its existence.

Regarding the second aspect, referring to the treatment given the subject by Zurbano’s critics, what jumps out is an additional difficulty in the eradication of racial discrimination in Cuba: the absence of cultural dialogue and debate that has essentially nullified the social sciences.

In Cuba it’s not possible to have a basic, objective dialogue without transgressing the limits imposed by the dominant ideology. This is a sufficient obstacle to destroy the effectiveness of debate over solutions to social problems. In this sense the statement of Guillermo Rodriguez Rivera: The Cuban Revolution not only began the struggle against racism and discrimination but nor can one can say that this struggle had never been so deep as in this moment of our history, it’s a proposal that completely lacks foundation.

In another part Rodriguez Rivera noted that Zurbano should investigate the subject with his elders. This and other proposals of Zurbano’s critics reveal the limits established by the powers-that-be which comply in part with intellectuality; a behavior which tends to paralyze thought and debate, at the same time classifying within the absurd and worn down categories of friends and enemies those who think differently from what is permitted.

Without failing to recognize the role played by some emerging spaces for debate, the complexity of the subject of race in Cuba makes necessary public debate, where, paraphrasing Victor Fowler, all points of view participate.

Racial discrimination is and continues to be a serious obstacle towards sharing a common destiny among all Cubans. For all of these reasons, the controversy provoked by Zurbano’s article should be converted into a road towards reaching a consensus among all possible solutions to the unresolved subject of racial discrimination.

FS: My second question is about the problems of persistent racism is: from your point of view what could be the essential lines of a solution?

Dimas Castellanos: I believe the essential lines towards a solution should emerge from research, political debate and consensus. No one holds the truth in his hands, but we can shape it among all of us. What is clear, as history has shown us, is that eradication does not only depend on the proclamation of laws, which is what has been done since the birth of the Republic until today, but also from a multidisciplinary analysis of its origin, development and treatment.

FS: And my third question on the subject: What relations might these problems have with the definition, evolution and development of our national identity?

Dimas Castellanos: If we understand that a nation–from the sociological point of view–is the fusion of principle social factors that make up a country, resulting from a long process of closeness and social, cultural and economic integration that gradually drives unity across difference, in a moment of history and in a determined territory, then the relation of the subject of racial discrimination is determined by the evolution and development of our national identity, since sharing a common destiny is impossible in conditions of inequality. This is the remaining challenge.

FS: Finally, I should tell you that this is the first time we are interviewing you; perhaps in the future we will have to come back to these subjects, but before we finish I want to ask you if you have something you’d like to add to this publication.

Dimas Castellanos: The Conviction that the situation in Cuba will not find a viable exit, until both liberties and rights are permitted, first of all, the reconstruction of the concept of citizenship, today absent, and from there confronting the many challenges that Cuban society has in front of itself, to be able to insert itself into the age of globalization, information and new communication technology which has its starting point in the total incorporation of Cuba into the international agreements on human rights.

fsautie@yahoo.com

Notes:

[1] Cimarrones are runaway slaves: slaves fleeing their masters who lived solitary lives in the hills.

[2] Apalencados, stable communities of runaway salves, were located in areas difficult for their persecutors to access, such as shantytowns. Made up of a series huts, they were characterized by economic self-sufficiency.

[3] T. FERNANDEZ ROBAINA. Black in Cuba 1902-1958, p. 144

Unicorn, Sunday June 16, 2013

24 July 2013