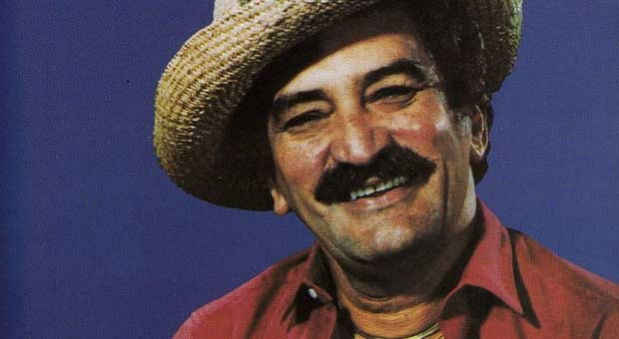

Before starting my post graduate program on Cuban popular culture, I believed that the members of my family were the most funny and original people on the planet. This opinion lasted until I heard of Guillermo Alvarez Guedes, I sat down with his 32 albums and I bottled myself up in the enviable task of starting down the road of his work. It didn’t take long for me to notice the inarguable truth: everyone in my family had been stealing Alvarez Guedas’s jokes for years.

My story is not unique, and it shouldn’t be. I have heard his jokes time and again over the informal network in which they travel–from person to person and increasingly over email and sites like YouTube.

It was precisely by means of informal networks that Alvarez Guedes had the opportunity to cross borders with his sense of humor. His discs are considered contraband, clandestinely brought into Cuba and enjoyed by Cubans who elude the restrictions of the government for the chance to have a good guffaw. His work also crossed generational borders. From the news of his death, commentaries from Cuban Americans abound in remembrance of his albums as a species of comedic soundtrack of their childhood.

One of the most common forms of remembering Alvarez Guedes has been to tell his jokes. While many of them are “eternal,” that is to say, they maintain their comic effect far beyond their original representation, this romantic strategy of remembering doesn’t completely enclose the complex relation between the spectacle of Alvarez Guedes and the social context in which he acted. What can some of his famous spectacles on the story of his exile?

Miami, hasn’t always been a place that welcomed immigrants from Latin America. In the 60s and 70s many in Miami felt certain resentment toward the newly arrived from Cuba, they put up signs “no Cubans allowed.” Tensions became even more serious in 1980, when because of the Mariel exodus this antagonistic feeling grew on a local and national level. Apart from the negative coverage on the part of the press, this was the period which gave rise to the English Only movement, with the purpose of creating an anti-bilingual referendum which was passed in November of 1980, became law, changed the bi-cultural policy and bilingualism established in Dade County since the beginning of the 70s.

Some of Alvarez Guedes’s jokes, such as the Clase de idioma Cubano, and his most successful album, How to Defend Yourself from the Cubans (1982), still make us laugh today at how they suggest the idea of a class where they teach bad words to an imaginary audience of North Americans. It is is precisely in this tour that they talk about the aforementioned difficulties faced by the exiled community in which Alvarez Guedes acted as a typical guy, a spokesperson for exile, resisting the so called cultural integration and at the same time driven by his own cultural identity. To subject Cubans to trail in a jury of public opinion, Alvarez Guedes mobilized the joking to invert the existing power dynamics in Miami.

In many of his jokes on language, the Northamericans observed from outside, in the role of foreigners. In How to Defend Yourself from the Cubans, Alvarez Guedes acted primarily with a slight English accent, demonstrating the culture shock of the cultures in two languages and joking also with the locals. In representing his mastery of English and invoking the familiar codes of joking, Alvarez Guedes makes a defiant declaration against the models of North American integration and at the same time emphasizes the vitality of the community of exiles.

Humor has been a mode to narrate and analyze the political reality that the Cuban community has faced since the colonial era into the present. The legacy of Alvarez Guedes will always be the jokes that have been enjoyed and will be enjoyed by so many generations both on and off the Island. Guedes was not a political commentator, but his humor frequently told popular stories such as compatriots navigating the lived reality of exile, a reality outfitted with the political charge that inevitably was brought up from the conditions of the expatriated.

Taken from Diario de Cuba.

10 August 2013