Miguel Luna drawn by Abel Prieto, in Viajes de Miguel Luna.

“The day that rabble gets into the UNEAC*, we’re lost.”

– Abel Prieto, from his Viajes de Miguel Luna

What does a Minister of Culture think about when he turns into an author? What does he aesthetically cling to and what does he judge as too politically incorrect to include in his work? Does he play? Does he confess? How does he balance the influences and disguise the secrets of the State? Does he compare his stories with the classics of the Cuban canon or only with his contemporary competition? Does he censor himself? Is he sucking up to or betraying his superiors (His Superior)?

Viajes de Miguel Luna is an invaluable document for dissecting the mind of citizen Abel Prieto, public official in the upper echelons of power during the last two decades of the Revolution. Literally, the last. And the most profitable from the point of view of fiction: those of the decline and fall of just about everyone, here on the Island as well as in Exile.

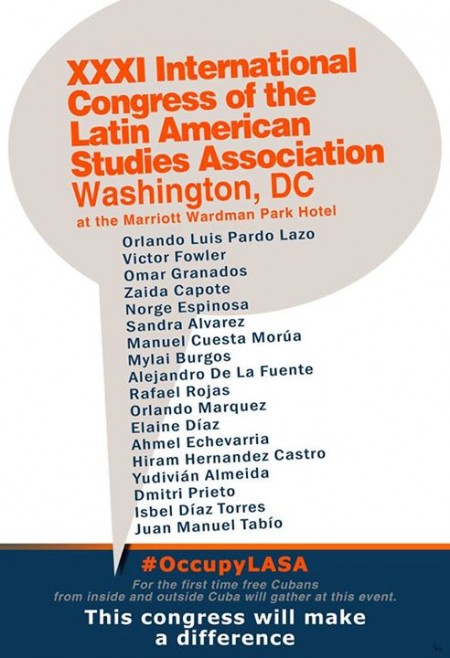

The official presentation, in February 2012, at the Book Fair of the Cuba Pavilion, required (perhaps due to the bulk of the novel, 540 pages) three veterans in turn: Graziella Pogolotti, Eduardo Heras León and Rinaldo Acosta. To this was added the presence of Ambrosio Fornet, Roberto Fernández Retamar, Eusebio Leal, Miguel Barnet, Frank Fernández, Fernando Martínez Heredia, Reynaldo González and, of course, his predecessor in the post, transformed that evening into an involuntary vision of a generational wake.

A devotee of Lezama among the earliest after the death and burial of Lezama (between the ambulance sent by Alfredo Guevara and the bugs planted by the secret police), at last Abel Prieto achieves the miracle of a book as arduous to read as Paradiso, although for diametrically opposed reasons: Lezama’s magnum opus is an untranslatable labyrinth that forges its very reader (the rest get burnt out); while Viajes de Miguel Luna is the spasm of the legibility of Cuban dialect loud and clear (quasi-military jargon), an anecdotal hyper-transparency that ends up overstuffed (the accursed circumstance of the drivel-ography of Miguel Luna, or “Mick or Mike or Miki or Mickey Moon or simply Mikimún” from all sides).

In a Stakhanovite effort of “popular dissemination”, written like volunteer work from behind his political desk at the Ministry of Culture or the Central Committee of the Communist Party, this is the sympathetic saga that the New Man had been expecting to read since 1989 (the perestroika on paper); it is the coming-of-age story that our middle class cried out for, demanding a relief from the vacuum of this Imaginary Era of transition toward State capitalism; it is the best seller that we intellectuals can give as a gift on a Sunday in May to our mothers (without awaiting the death of a Rosa Lima, such an affectionate repressor); and it is, also, more than a travel epic, the last of the “scholarship novels” of 20th century Cuba, that genre that was born senile, yet has yielded so many functionaries during peace time.

There is a lot of kitsch in this type of tropical gaiety in the gulag: from Marcos Behmaras to Enrique Núñez Rodríguez, from José Ángel Cardi to F. Mond, among other ourselves-and-others, the text wants to laugh but what comes out isn’t a smirk, but something worse: a grimace (rigor mortis of the State). Falsehood as poetic license used by a bully in search of authenticity. Because here we won’t find even traces of the stigmatizer of young Cuban artists, nor of the audiovisual censor, nor of the manipulator of pro-Cuba solidarity movements, nor of the hijacker of Cuban exit permits, nor of the bandit-hunter setting his sights on the Encuentro de la Cultura Cubana magazine, including the coercion of this island’s hostages who collaborated with it (a publication that, after observing a minute of silence at UNEAC when its editor/founder died, they finally managed to sabotage). But it is precisely these omissions that open up a bridge, a great bridge to our residual freedom in so many perverse readers. Thus, the archeological eloquence of these Travels of Miguel Luna will face the researchers that will descend from, let’s say, North American academia to celebrate the Great Centennial of 2059 — mulg-kästrismo beaming as one of the fine arts.

The proof of success, guarantor of an imminent Critics Prize and perhaps a National Literary Prize, is that this book by Abel Prieto is nowhere to be found inside the country: it sold out before its introduction into the market! This will not impede Abel Prieto’s trips now to collect praise and euros from a parliamentary Europe suffering from nostalgia in its terminal stages, plus the corresponding thousand and one translations of this work, including into Mulgavo: a dead post-socialist language (part Basque, part North Korean, part Iranian?) in which an unbearable percentage of monologues of our “Kübb-hím-póet-Míkel-Lún” are written (the ex-minister uses Mac or gets by with the accent marks in Microsoft).

It is curious that Cuban literature (the same as with the more recent Dictionaries of Cuban Literature) does not dare over-mention that dystrophic year of 1989. In style and theme, we are nailed to a remote, ludicrous past: Cuba’s trauma is that no holocaust will be tragic. Our day-to-day amnesia can’t withstand it, and we lack the capacity to narrate the horrifying void of a nation forced into fidelity, at the whim of a personalistic power that made us live un-chronologically outside of global history, anachronistically in that stop-motion time of absolute totalitarianism.

Abel Prieto, upon writing (or dictating to his deputy ministers) the screenplay of this Goodbye Lenin awash in semen, need not be the exception: the action transpires in hops between the September 29 of 1948 and the September 29 of 1989, while the author’s alter-ego masturbates from the start (over the fields and cities goes the onanist…), while Congolese hutias as demonic as they are endemic (pardon the redundancy) masturbate, while the masses and sub-Soviet leaders of the putative proletarian utopia masturbate, while the mobs rush out to shoot themselves to death, no sooner does mulg-demökratia arrive in the Pastoral Agricultural Democratic Popular Socialist Workers Republic of Mulgavia. It’s obvious that Abel Prieto can see the processes of change like a blitzkrieg of mafias (Mulgavo-American?) and fluorescent McDonald’s icons, where today’s communist hierarchs will without doubt be masters of war and capital (let us trust that it will have been for health reasons, not this kind of imagination, which will have cost him his ministerial purse). Of that hypothetical country that yesterday was associated with Cuba, we know nothing after page 540 (Wikipedia isn’t God either). For the author, it probably wasn’t worth wearing oneself out on an anti-climax of economic growth, the opening of borders, respect for human rights and, if it’s not too much to ask, the training of Mulgavan Boy Scouts by People in Need to fratricidally undermine a still surviving little revolution in the Caribbean Sea. I don’t recall even one single mention of the word “revolution” in the novel, as if this situation were out of context, of zero influence on the thesis (even though “counter-revolution” is mentioned and even provokes a fainting spell in a supporting character: someone taken out of the novel who writes the character who in turn is written by Abel Prieto). Ecstatic with retrospectives that cover up any association with local historical horror, the jovial jargon of the sexagenarian Abel Prieto achieves a novel for all and for the good of all. It doesn’t matter that he himself could have gone to jail for daring to write it in real time. It doesn’t matter that he would have been shot by firing squad without trial for having published it then in the “Red Island in the Black Sea”. What is transcendent here is that all future time must be better (an idyll of the Left), and that this text in Cuba now proves it against our Eternal Enemies. Thus, due to its ecumenism or maybe its communist Catholicism, from the theorist of global anti-imperialism, to our provincial dissidents with “Made in Miami” digital copyrights, all should find something to praise in this mammoth opus by Raúl Castro Ruz’s current salaried subordinate. Congratulations! I suppose the consensus-building had to start somewhere.

What does an advisor think about when he turns into an author? What does he politically cling to and what does he judge as aesthetically correct to include in his work? Is he free or does he run every concept by State Security? Does extensive writing distract his parliamentary concentration, is it a diversion of resources from the Council of State, or is it simply an extracurricular hobby edited in record time by Letras Cubanas publishing house? Is this an exemplifying work meant to monitor the literary market (for good reason, the novel imparts a Delphic mini-course on adolescent-adventurer readings)? Will Abel Prieto retire with this dramatic effect or is he already plotting a new hilarious project for his next two decades in power?

In an interview, the author implores us to not abandon reading his work until the KONIEC** (“not because it’s so good, but because I’d like it if someone reached it”). As with Paradiso, in effect, I recommend resisting until the bitter end the half-a-millennium of pages in Viajes de Miguel Luna. Maybe this is the novel that, since the “Revoluzoic Era”, Armando Hart should have written for us? This is a book that can be put to use as a Rosetta Stone of 21st century socialism, Cuban style, and it includes, as a bonus track, a histrionic colophon that parodies, or maybe pays homage to, the telenovela writer Mayté Vera, not to mention half of a century’s worth of excellent vignettes signed by the author (the untapped potential of a Marjane Satrapi emanates from Abel Prieto, self-portrait included).

Mikimún has died, long live the Ministrún. Quod scripsi, is crisis.

Translator’s notes:

* National Union of Writers and Artists of Cuba

** This is the Polish term for “finish” or “end”.

From Diario de Cuba

Translated by: Yoyi el Monaguillo