1. March 12, 1965, an open letter by Ernesto Guevara to his friend Carlos Quijano is published in the Uruguayan weekly Marcha. The text, “Socialism and the New Man in Cuba,” is perhaps Guevara’s most significant theoretical writing, and at the same time an emphatic declaration of the regime’s objectives emanating from the Cuban Revolution, then already declared Marxist and in the full process of converting the island to socialism.

Maybe nowhere else is the regime’s intention to intervene in all segments of Cuban society enunciated so clearly, to radically transform the mental and physical life of its citizens and to produce a new subject: the New Man.

That desire to regulate the existence of individuals and to act on the biological functions of life — even regardless of political action — is not, of course, exclusively of the Cuban regime and not even of socialist systems. As Michel Foucault discovered, it has to do with a fundamental characteristic of the power of modern western societies.

Then still leading the Cuban Ministry of Industry, Guevara writes in that letter: “In order to construct communism, simultaneously with the material foundation, one must make the New Man.” The job, he warns, is not simple: “The defects of the past are transferred to the present in the individual conscience” and, in order to eradicate them, individuals “must be subjected to stimuli and pressures of a certain intensity.” continue reading

Those stimuli and pressures may be of “moral character” or well managed, sometimes brutally, by the revolutionary institutions, that “harmonic collection of well oiled channels, steps, dams, devices” that guarantee “the natural selection of those destined to walk the vanguard.”

In that “dictatorship of the proletariat, exercising not only over the defeated class but also, individually, over the victorious class,” of special importance is the educational machinery of the State, now that it acts directly on the youth, “malleable clay with which it may construct the New Man without any of the previous defects.”

One of those youth is named Reinaldo Arenas, and he is not, in spite of his last name, “clay” and even less “malleable.” Then, when “Socialism and the New Man in Cuba” is published, Arenas is 21 years old and is about to enter for the first time into conflict with the Revolutionary regime. That year the State creates the Military Units to Aid Production — rehabilitation and forced labor camps for “social misfits” — and stirs up its homophobia.

That same year Arena finishes his first novel, Singing From the Well, and tenders it to a national competition where he receives honorable mention — the beginning of his difficulties, acrimonious relations with the cultural bureaucracy of the island.

It is then–when the radicalization of the Castro repression and the emergence of Arenas as a public figure coincide–that the frictions begin between the writer and regime, frictions that soon evolve into a full and asymmetric confrontation, whether because Arenas is homosexual, whether because he publishes his works abroad, whether because he resists the disciplining processes sponsored by the State.

During the next 15 years Arenas will endure the harassment and punishment of the devices of state power: He will be forced to work on a sugarcane plantation, will be locked away in a prison, forced to sign a public retraction and will see his repeated efforts to leave the island frustrated, until 1980 during the Mariel exodus, he manages to leave for the United States.

It is there–at odds with the Miami Cuban exiles, first encouraged and then stunned by life in New York and finally sick with AIDS–where he finishes writing Before Night Falls, the memoirs that he began to write one day in 1973 in the culverts of Lenin Park while hiding from the regime’s security forces.

2. “All dictatorship,” writes Arenas in a passage from Before Night Falls, “is cold and anti-life: every manifestation of life is in itself an enemy of any dogmatic regime. It was logical for Fidel Castro to chase us, to not allow us to fornicate and to try to eliminate any public display of life.”

This image of the State that censors the “public display of life” and toils to control the physical existence of its citizens, is repeated time and again throughout the 343 pages of the book.

Whether the regime grants itself “the power to instruct how men should dress,” or proposes “to break ties of friendship” through organization, street by street, of the Defense of the Revolution Committees or penalizes homosexual relations, the image that emerges here is that of a power for which the life of its citizens does not represent the boundary of the political but precisely its center and objective. In other words, a biopower, that, in order to continue being such, must intervene in and regulate all vital aspects of the population.

Not coincidentally Arenas lingers, in Before Night Falls, on the description of three of the disciplinary and standardization devices of the Cuban regime: education, forced work and prison. A member of the first generation of university students educated by the Revolutionary State, Arenas recreates those years not as a period of formation but rather of indoctrination in a college that, in agreement with his words, was a “monastery where new religious ideas prevailed and, therefore, new fanatical ideas” and where “it was not easy to survive all those purges that had a moral, religious and even physical character.”

Years later, in 1970, Arenas is sent to a sugarcane facility, the Manuel Sanguily Center in Pinar del Rio, in order to cut cane and write an elegy of the Ten Million Ton Harvest. There he comes across a new generation of youth, no longer indoctrinated in college but peons in a forced labor campaign: “those young men of sixteen, seventeen years, treated as beasts of burden, had no future to await nor a past to remember. Many gave themselves a machete blow to the leg, or cut off a finger, any barbarity so long as they did not have to go to that cane plantation.”

Instead of “ideologically guiding” that youth, Arenas is accused of perverting it. More specifically: in the autumn of 1973, he is accused of having abused, together with another friend, two minors, charges that he denies. In order to avoid being arrested, he hides for four months in the most unexpected places (behind a buoy in the sea, in the crown of a tree, under a bed, in the culverts of Lenin Park), in a series of misadventures almost worthy of Brother Servando Teresa de Mier that he had reclaimed and re-invented years before in the novel Hallucinations (1969).

When finally he is detained, in January 1974, he is locked away in the Morro prison and two months later is transferred to Villa Marista, headquarters of State Security, where he is forced to sign a retraction in which he “repents” equally his homosexuality and his literary works and promises “to rehabilitate himself.” Immediately he is returned to Morro and a little later taken to an “open” prison on the outskirts of Havana until the beginning of 1976 when he is finally “freed.”

These events, from when Arenas is accused until he is set “free,” occupy two and a half years of his life but almost a fourth of his autobiography. It is in those pages where the most repressive edges of the Cuban state appear, as in this passage about the torture in Villa Marista:

“One day I began to sense in the next cell a strange kind of noise that was as if a piston were releasing steam; after an hour I began to hear piercing screams; the man had a Uruguayan accent and was screaming that he could stand no more, that he was going to die, to stop the steam. In that moment I understood what that tube next to the toilet of my cell–whose meaning I had ignored–consisted of; it was the conduit through which they supplied steam to the prisoners’ cell which, completely closed in, became a steam room. Supplying that steam became a kind of inquisitorial practice, like fire; that closed place full of steam made the person almost die of asphyxia.”

3. Images like this are repeated throughout the central pages of Before Night Falls and make one think, often, of typical scenes of prison literature. That is not, however, the most surprising thing in this autobiography: not the sordid portrait of the Cuban regime Arenas paints but the way in which he himself confronts that power.

Said another way: the most singular thing about Before Night Falls is not so much the denunciation of Castroist repression — present after all in the texts of many other writers and in the reports of various human rights agencies — as the characteristics of Arenas’ resistence, very different from the usual opposition of liberal societies and little akin to that liberal platform from which critics of the Castro regime usually shoot. In a sentence: Arenas’ resistance — alive, corporeal, erotic — shares not a few of the notions of the same biopower that he confronts, and thus could be characterized, if one wishes, as a biopolitical resistance.

Reading the first volume of the History of Sexuality by Foucault, Thomas Lemke notes that “the processes of power that seek to regulate and control life provoke forms of opposition that frame their claims and demand recognition in the name of the body and of life itself.” That is to say, and Foucalt himself indicates: “Against that power […] the forces that resist support themselves on the same thing that is at stake, that is to say, life and man as a living being.”

It no longer has to do with a resistance that happens exclusively in the public sphere, or that concentrates its action in the electoral processes, or that pursues a realignment of institutions or portion of the power at stake. It has to do with a resistance that takes place everywhere all the time, that employs as a principal tool the bodies of those who resist and who oppose, fundamentally, the policies of normalization and discipline dictated by power.

It suffices to review once again the pages of Before Night Falls in order to notice that the resistance of Arenas is, without doubt, of that type. One must see: although decidedly opposed to the regime, Arenas does not try to defeat it through political means nor to suggest the possibility of organizing a political group against it. In the same way, he seems to disbelieve in the value of the dialog of ideas and even reproves those dissidents who declare themselves in favor of dialog with the Cuban authorities.

Maybe even more revealing is that there is not in all his autobiography a single moment of nostalgia for that political order in which life was the limit, the “other side,” the “outside,” of politics.

To the contrary: that troubled partnership between life and politics provides the body and its eroticism an intensity that Arenas extracts in exile, now in New York, where homosexual relationships seem to happen routinely without transgressing any rule.

In the same way, Arenas does not seem interested in restoring autonomy — always relative — to the literary field or in distancing literature from political struggles. Neither does he seem to want to restore the old limits between the public and the private and still less to return sexuality to the side of the private sphere.

If he did desire it, he would do it: would reserve stories about his erotic life for himself and write literary works — dense, difficult, proud of his “autonomy” — distant from political circumstances. It is clear that he does not do it: he writes, almost without exception, works that are bellicosely political and publicizes in them his homosexual experiences. That is, in fact, his most effective political strategy: the repeated exhibition of himself.

The first image of the first chapter from Before Night Falls is that of a healthy and one would say almost new body: “I was two years old. I was nude, standing; I leaned over the ground and ran my tongue over the earth.” The last image is of a sick body, infected with AIDS and sapped by cancer, that contemplates the moon while awaiting death: “And now, suddenly, Moon, you explode into pieces before my bed. I am alone. It is night.”

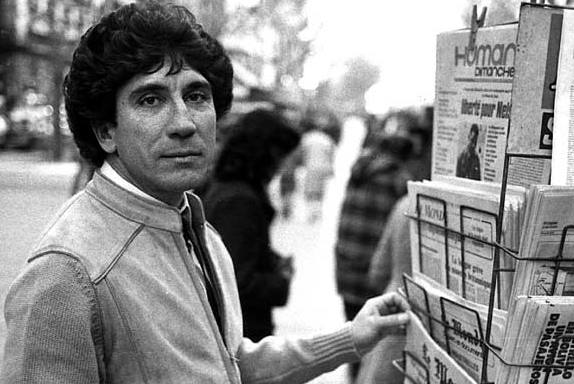

Between one moment and another many other images of Arenas occur, of Arenas’ body, almost all textual but also, in the middle of the book, some photographic. In almost all of them Arenas’ zeal to present his body stripped of metaphors is evident, outside the categories with which states and ideologies usually dress bodies.

He exhibits his body to show the arbitrariness of all those labels — bird, dregs, proletariat, male, Cuban — to which they have wanted to reduce it. He exhibits it, also, as if dealing with a trophy: the proof that his body, in spite of repeated efforts to repress and standardize it, remains volatile and desirous.

So he remains today also, 23 years after the disappearance of that body, the ghost of Reinaldo Arenas: disobedient, incorrigible, amazing.

From El Universal, 14 December 2013

Translated by mlk

HAVANA, Cuba – In the Cuban capital, two cooperatives operate the old public routes of the so-called taxis-ruteros, microbuses which take passengers from the Parque de El Curita, to four destinations: El Náutico, Alamar, Santiago de las Vegas and La Palma.

HAVANA, Cuba – In the Cuban capital, two cooperatives operate the old public routes of the so-called taxis-ruteros, microbuses which take passengers from the Parque de El Curita, to four destinations: El Náutico, Alamar, Santiago de las Vegas and La Palma.