When the high creole hierarchy enjoyed the arrival of the 51st anniversary of the insurrection which elevated them to power on 1 January 1959, a violent cold front was ravaging the west of the country.

When the high creole hierarchy enjoyed the arrival of the 51st anniversary of the insurrection which elevated them to power on 1 January 1959, a violent cold front was ravaging the west of the country.

In Mazorra, a psychiatric hospital located on the highway that leads to the principal airport, a major scandal was uncorking itself.

The pathetic photos that circulated by the Internet and the reports of bloggers and independent journalists obligated the regime to publish a little note. Weeks later, noiselessly, those words got the Minister of Health, José Ramón Balaguer, fired.

It was the start in a chain of bad news that marked 2010 in Cuba. In February, the political prisoner Orlando Zapata Tamayo heated up the path. After 86 days on a hunger strike claiming a handful of rights, he died in a hospital in the capital. His death provoked an avalanche of criticism towards the Castro brothers across the entire planet.

The death of Zapata launched a series of widely publicised marches by the Ladies in White, a group of women, wives, mothers, and daughters of opposition members condemned to long sentences in March 2003.

The government didn’t take the blow well. Little accustomed to those who annoy, concealed violence was used against the Ladies, by means of supposedly spontaneous mobs who were admirers of the Revolution. Aggressions against these women, who carried gladioli in their hands through Havana streets demanding freedom for their family members, threw more wood on the fire in the agitated Spring of 2010.

Civilized nations hit the roof and a series of economic restrictions were brought down to pressure the government of Raúl Castro. The General took note. This oven wasn’t for baking cakes.

Cuba lives on the edge of bankruptcy. The economy is shipwrecked. The country is taking on water on all sides. For the first time in 51 years, the government threw in the towel before the street marches of the Ladies in White and a new hunger strike, started in Villa Clara by the opposition member Guillermo Fariñas, who was demanding the release of 26 dissidents.

In a rare diplomatic pirouette, the regime obtained the help of the forgotten Catholic Church. In a hurry, Raúl Castro asked Cardinal Jaime Ortega to intercede with the bothersome women. He designed a three-phase plan. From Madrid, the ex-chancellor Miguel Ángel Moratinos dressed it up well. The agreement was made public on June 8, and it was made known that 52 political prisoners would be liberated.

The governors’ strategy was to build a gold-plated bridge for the freed opposition members so they’d fly to Madrid. They thought that a friendly telephone call from the Cardinal to each prisoner, inviting him to leave headed for exile, would be accepted by all the prisoners. It didn’t work out that way. As a weapon of coercion, the regime still has not freed 11 dissidents who refuse exile.

While the news of liberation of political prisoners made a trip around the world, Fidel Castro, historic leader of the Revolution, rose from his sickbed. A recuperated Castro. With a distinct look, with Adidas or Nike sporting overalls. Or a collection of shirts. He did what he knew best: Spoke and predicted. He unleashed on the world a red alert; a nuclear war was just around the corner.

Besides prophesying chaos, the ancient guerrilla is one of those convinced that capitalism’s days are numbered. He chatted about everything happening on the Earth. But he did not delve into local issues; that was a matter for his brother.

They started to play in different leagues. Raúl, hand to the grindstone, seeing exactly how 12 million Cubans bring their meals to the table. And the visionary Fidel, in charge of international affairs. One suspects disagreements, but in 2010 each stuck to his own area. For the time being.

In July, summer arrived. School vacations, beach, and fans celebrating the victory of Spain in the World Cup in South Africa. Earlier, Habeneros had celebrated that their team, the Industriales, was crowned champions in the national baseball series.

In the offices, in full heat, the technocrats worked at full throttle on a unique, new, dedicated plan to reform the disastrous economic situation. Recipes with a raft of shock therapies, similar to those applied by countries in bankruptcy.

When their vacations ended, Cubans were awaiting the news that 1.3 million people would be laid off in three phases. The first one already started in October. It was not the only one. State subsidies have to be cut back. Open the tap for self-employment. And apply a tax rate that sometimes reaches 40% of income to alleviate the terrible State budget deficit.

People aren’t expecting miracles with the opening-up of private initiative. It smells bad. The elevated taxes are disheartening. The insufficient guarantees offered by a government that openly rejects people who succeed in making money are strong elements that generate mistrust.

In different provinces there were attempted protests and the streets have become dangerous. as if the police didn’t have enough to do going after crimes and drugs. Urban transport — like housing — gets worse as time goes on. The ration book stays the same and the scarcity of products — in pesos or in cash — continues to be a source of alarm. When rice isn’t lacking, there are no beans. If there is salt, there is no sugar.

In the year that just ended, we see more beggars, drunks, prostitutes and thieves in the streets. Domestic and school violence just skyrocketed. And courtesy has continued to be something from another planet.

Despite the black panorama with its grey backstitches, Cubans continue to dance, sing, make fun of the governors and make love wherever. Television viewers were still hooked on Brazilian soap operas and little girls were dazzled by Hannah Montana.

In 2010, among others, there were three “round” anniversaries: the centennial of the birth of the actress and singer Rita Montaner, and of the writer José Lezama Lima, the 90th of the ballerina Alicia Alonzo, and the 80th of the singer Omara Portuondo. Four compatriots were honored with Grammy Latino prizes: Chucho Valdéz and Leo Brower — residents of the island — and Arturo Sandoval and Alex Cuba, settled in the United States and Canada.

The good news was that we weren’t lashed by any tropical storm or hurricane of great power. And one bit of bad news, that the hoped-for increase in tourists from the United States didn’t materialize. A consolation prize was that friends and family from the United States, once again and despite the crisis, haven’t stopped helping their families on the other side of the puddle. With money or with packages of food, clothing, medicines, and toys.

Cubans are wishing that 2011 might bring good omens. They think things probably can’t get any worse. Things have been scraping bottom for too long. Living at the edge of the abyss.

December 30 2010

Marta Lopez has wanted to emigrate to the United States of American for some years now. She signed up for the 1998 American visa drawing, but was not lucky. In 2001, her mother went to visit in the United States and stayed. The monthly remittance she sent Marta allowed her to build her house. Exit from the country was no longer her only option.

Marta Lopez has wanted to emigrate to the United States of American for some years now. She signed up for the 1998 American visa drawing, but was not lucky. In 2001, her mother went to visit in the United States and stayed. The monthly remittance she sent Marta allowed her to build her house. Exit from the country was no longer her only option. A young lawyer who sometimes invited me to his trials told me a few days ago about something unusual that happened in the Territorial Military Court in San Jose de las Lajas, to the south of Havana, where some Santeros filled the judges’ stand with dust, seeking a favorable result for their relatives, implicated in serious crimes. His client didn’t contract for the services of any witch, but received an unexpected penalty just like the other defendants.

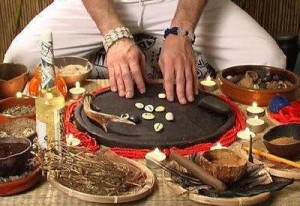

A young lawyer who sometimes invited me to his trials told me a few days ago about something unusual that happened in the Territorial Military Court in San Jose de las Lajas, to the south of Havana, where some Santeros filled the judges’ stand with dust, seeking a favorable result for their relatives, implicated in serious crimes. His client didn’t contract for the services of any witch, but received an unexpected penalty just like the other defendants. A friend notes that this is more common than many assume. Some believe that the engagement of a palero, a Santeria practitioner, can reverse the outcome of the trial and “soften the prosecutor’s proposal, tie the tongue of the attorney if his client is on the opposite side, or put into the mouth of the judge the orders of the “pot,” linked to the dead who assist the practitioner, who speaks with them through a complex system of divination that passes through the interpretation of the snails and the feeding of animals like a rooster, goat or sheep.

A friend notes that this is more common than many assume. Some believe that the engagement of a palero, a Santeria practitioner, can reverse the outcome of the trial and “soften the prosecutor’s proposal, tie the tongue of the attorney if his client is on the opposite side, or put into the mouth of the judge the orders of the “pot,” linked to the dead who assist the practitioner, who speaks with them through a complex system of divination that passes through the interpretation of the snails and the feeding of animals like a rooster, goat or sheep. The defense attorney doesn’t worry about “the mess in the pot” because he believes that every trial is a theatrical performance under pressure from above, through money or the police they invoke “secret operational tests” that complicate things for the accused, leaving the defense at a disadvantage, unless the Head Judge, committed to fairness, disregards the testimony of those in uniform.

The defense attorney doesn’t worry about “the mess in the pot” because he believes that every trial is a theatrical performance under pressure from above, through money or the police they invoke “secret operational tests” that complicate things for the accused, leaving the defense at a disadvantage, unless the Head Judge, committed to fairness, disregards the testimony of those in uniform. José, with his 35 years, dreams of driving a convertible silver Audi. His eyes are open, it was not difficult for him to come back to reality when his fan stopped due to a blackout. The heat of the night activates his brain. He thought of a solution for his existential problems.

José, with his 35 years, dreams of driving a convertible silver Audi. His eyes are open, it was not difficult for him to come back to reality when his fan stopped due to a blackout. The heat of the night activates his brain. He thought of a solution for his existential problems.

Not infrequently, the Cuban government has spoken out against anti-immigrant laws in developed countries. However, nobody could imagine that there are legal regulations on the island similar to SB 1070, which was passed by U.S. state of Arizona on April 23 and which authorizes state police to arrest people suspected of being an illegal immigrant.

Not infrequently, the Cuban government has spoken out against anti-immigrant laws in developed countries. However, nobody could imagine that there are legal regulations on the island similar to SB 1070, which was passed by U.S. state of Arizona on April 23 and which authorizes state police to arrest people suspected of being an illegal immigrant.