The impact of the attacks Yoani, victorious against the “demons” paid by the Cuban Embassy in the Brazilian capital, have become something of a legend in Brazil. After the Cuban blogger’s brilliant presentation, and a standing ovation, the next day there was a program in the city of Salvador, the capital of Bahia state.

However, before going to the university auditorium Tuesday night, the 19th, there was a phone call from the Brazilian documentary filmmaker Dado Galvão, inviting Yoani “and her entourage” to visit National Congress (it was an invitation from the Federal Deputy Otavio Leite in coordination with Senator Eduardo Suplicy) for which we were sent the corresponding plane tickets.

As we had planned some sightseeing in Salvador, this invitation forced a change of plans, with the Wednesday, February 20th program being to “visit to the Brazilian Parliament, in Brasilia.”

The Salvador-Brasilia flight would leave around noon, which gave Yoani the chance to have another informal session of interviews that morning in “Feria de Santana,” in the hotel lobby where we were staying. Our hotel was also occupied by many of the journalists who were accompanying us everywhere, which facilitated, for example, privileged coverage of the previous day’s lunch, in a typical Bahia restaurant to which we directed our little bus, also filled with our journalist friends.

When people in the restaurant recognized Yoani there was a kind of flocking to her, to take photos, hug, apologize for the actions of the “bad Brazilians.” The owner of the place brought his wife and daughter for the requisite photo and sang, on a small stage, traditional music in honor of Yoani and in addition, obliged the Cuban to dance with him, which Yoani originally declined, “I’m Cuban, but not a dancer,” she said. It seemed he was partnering a “Madonna” or a “Micheal Jackson” rather than a young brave Cuban blogger.

After breakfast in the hotel (with the obligatory photos of Yoani with its employees and their families) we traveled toward Salvador in the same minibus we used the entire time in Bahia. There were no demonstrators because the program has been changed to go to Brasilia. What we experienced at the airport was repeated at every appearance by the Cuban in previously unannounced places: great solidarity, photos, hugs, especially from women, who immediately sympathized with that fragile figure, smiling even in the midst of the greatest adversity.

At the entrance to the airport I separated from the committee to go with the “Feria de Santana” organizers to arrange the formalities for sending our bags and checking in at the airline offices and getting the luggage tags. All this was done at great speed, because “they were the belongings of the Cuban blogger.”

Despite my being delayed with the paperwork, when I entered the domestic flight area, Yoani hadn’t even made it half the distance. Everyone wanted a photo, a hug, to offer words of support, repeating, “I’m sorry Yoani, they don’t represent the Brazilian people.” We embarked for the main center of Brazil’s political power.

We got to Brasilia in the early afternoon. At the airport waiting for us was Deputy Otavio Leite, Representative to the Federal Chamber from the state of Rio de Janeiro, (and the classic battalion of journalists), with some of the deputy’s aides who immediately took care of our luggage. Without the presence of demonstrators we took another minibus, between hugs and photos of Yoani with those who were there.

From the airport we were taken directly to the formidable National Congress building, with police cars in front and behind us. Along the way Yoani was taking photos of the grandeur of Brasilia, the Avenue of the Ministries, its gorgeous Cathedral, the Supreme Court of Justice building, the Planalto (presidential) Palace, until we pulled into the emblematic building of the Brazilian Parliament.

A multitude of parliamentarians, journalists, deputies and senators, who pressed in wanting to see her, photograph her, talk with her, the principal leaders of the National Congress. The path between the minibus and the Great Hall of Parliament (at that time in parliamentary session), was agonizing. A human current pressing on Yoani, pushing her through those corridors. We couldn’t have walked on our own feet, that special “political” human mass carried us in the direction of the Session Room.

Behind me I heard one of the security officers surrounding us say to one of his companions, “I haven’t seen this in Congress even on the day Fidel visited us.” In reality, there was a large presence of security agents, but useless, because inside the building there are only deputies and senators along with their aides, and all of them wanted a simple photo with the Cuban.

The crowd that led Yoani entered the Great Hall of the Chamber of Deputies — in session at the time — interrupted by the crowd. Yoani was led by Deputy Leite to the main dais, where the blogger greeted and hugged everyone at the table. The journalists’ flashes didn’t stop recording images. A Leftist deputy, who had the floor at the moment of the “Cuban hurricane in Brazil’s” eruption into the room mounted a lukewarm protest at having been interrupted “outside the rules,” and was immediately silenced by several by various parliamentarians present at the session, asking for “a little education before such a distinguished visitor.” From the Main Chamber we went to the room of the Foreign Relations Committee, where Yoani was received by prolonged applause from the parliamentarians present. A complete symbol: the informal representative of the Cuban opposition received a standing ovation in the Parliament of the largest country in Latin America, by deputies and senators from the most diverse parties, all democratically elected.

Yoani was placed at the center of the table from which the meeting was chaired. I situated myself strategically, just behind the blogger. To the right of the special guest was Deputy Leite, who chaired the session; on her left would sit, for a brief moment, the principal leaders of the Brazilian parliament who took turns occupying the seat and embracing and congratulating the blogger, constantly telling Yoani to look in one direction (where the photographer was) for the precious photo. Senator Suplicy belatedly came and stood at the far right of the table, greeting Yoani from afar with a wave. The session started, but for Yoani, besides having to pay attention to what was being said (it was my responsibility to alert her if something important was said), for our Cuban the whole session was a parade of senators and deputies coming to her from behind the table and placing themselves on one side; hugging her and pulling her into the corresponding photo.

At the beginning of the session of Congress to welcome Yoani, we heard the cries and slogans of the demonstrators sent by the Cuban embassy. In this case, we could hear them at a distant, muffled by the wall separating the Congressional hall from the outside, where protesters from the Cuban embassy were held at bay by security agents. At one point in the session, apparently some of those sent by the Cuban ambassador managed to get to the door of the room (we noticed a movement of journalists covering the event, who focused their cameras in the direction of the front door) but they failed to enter the room to interrupt the session, as they probably intended, “to not let her talk.”

Deputy Leite gave a brief introduction of Yoani and immediately gave the floor to the “Cuban blogger Yoani Sanchez.” Yoani said little, as befits an illustrious guest of Congress. She made no political references to Cuba or Brazil. She spoke as “a simple citizen,” referred to her blog, her work, spoke of her hopes as an activist for freedom of the press as a right of all free men of the world, and very quickly finished her speech, which led to the most dissimilar interventions top Brazilian legislators. There were many requests for the floor. The hosting deputy, Otavio Leite, before passing the floor to the deputies, presented them to Yoani, pointing out the main party leaders present at the meeting, and their party affiliation. There were parliamentarians of all parties, after which the audience had the floor. The interventions, rather than questions, were speeches of welcome and were filled with praise of the blogger’s work, many apologized for the verbal attacks that had been made, one of them even said something like: “we are in presence of the future president of a democratic Cuba”…

Standing behind Yoani I whispered in her ear, “Did you understand what he said.” Yoani had learned a little Portuguese and answered me, turning her worried face–as a sign that something complicated could happen–and looking at me said, “Yes, I understood.” Many of the interventions were not questions to the blogger, but rather words of welcome to Brazil as well as gratitude for her visit to Congress.

After the words of the parliamentarian who called her “future president” a deputy from the left took the floor. He was a member of one of the most far-left parties of the local political spectrum. The deputy censured the words of the deputy who preceded him, expressing that such phrases could “occasion unnecessary problems for Yoani,” that she at no time had suggested such a thing–he said–and what’s more, “Brazil has diplomatic relations with Havana and that phrase could mean a request for explanations to Congress.” The deputy asked Yoani four questions of “concern” to the Brazilian left which did not agree with the “acts of repudiation” organized by the Cuban embassy against Yoani: first, her position on the embargo; second, her opinion on the Guantanamo prison; third, her opinion on “the 5”; and fourth, the source of the funding for her trip. Yoani took the microphone to respond.

Yoani said what she had been repeating since coming to Brazil, but this time, it was to the “upper crust” of Brazilian politics and she targeted and deepened her points of view. She talked about the three reasons she considers the basis for wanting to lift the embargo; she talked about the American Naval base not being a Cuban problem and that activists in the United States are fighting to close it; about “the 5 members of the Ministry of the Interior” she expounded explaining they weren’t 5 but 14, that 9 had made agreements with the U.S. attorney’s office, accepting the allegations and implicating the five convicted, so no one was innocent, following which she added an ironic phrase, which was later debated by the exile in Miami.

Yoani said something like: “For me, they could be released, thereby saving Cuba the huge amount of monetary resources spent on the island for propaganda, both in Cuba and abroad, because there are many needs on the island, we are lacking many things.” It was not a “request for them to release the 5 members of the Interior Ministry,” it was an ironic comment, unhappily for the opponents in Miami, of course, for which Yoani later had to apologize.

With regards to the financing of her trip she explained the sources, already detailed in numerous public appearances. While Yoani spoke, the deputy who had posed the question–in a friendly way and very considerate of Yoani–showed surprise at the extent and precision of the responses, such that when Yoani finished, the deputy, who continued to be amazed, rose from his seat and came to the table to shake hands with Yoani, offering her phrases of praise and solidarity. Senator Suplicy also spoke at the meeting, referring to the “bad time” in “Feria de Santana,” explaining that when he coordinated this session of Congress with Deputy Leite he sent a letter to the Cuban ambassador (he gave Yoani a copy of the letter to the Cuban ambassador inviting him to Congress that day) to ask him to come as a guest, with views of a “civilized” debate with “the blogger Yoani Sanchez,” something that the Cuban ambassador, with the arrogance that characterizes him, declined. Now in an institutional framework, civilized and politically high level, again Yoani scored 100 points.

On leaving the Congress, the characteristic battalion of journalists battalion confronted Yoani, who answered interesting questions about her future political ambitions.

“I hope to create a newspaper when I return to Havana. That’s my principal mission after this trip. I believe in the press as an effective fourth estate and my role in a democratic Cuba is journalism, to be able to freely criticize what I deem to be wrong. I dream of a Cuba where the president is one more personality in the national life. Not even the most important personality. I’m not political, I do not have sufficient cynicism to be political.” And with that Yoani capped a fundamental day.

(To be continued)

Articles by this author can be found at http://www.cubalibredigital.com

1 March 2013

The villainy of “Feria de Santana” was executed also against one of the most loved and respected senators among Brazilian politicians, Eduardo Suplicy, with recognized militancy on the left, the objects of insults and disrespect from the bloodthirsty mob. What happened was an act of unacceptable intolerance, not only against an supposed “CIA agent” blogger, as they wanted to see it, but an attempt by a foreign country (the Cuban government) to define the course of internal policy South American giant.

The villainy of “Feria de Santana” was executed also against one of the most loved and respected senators among Brazilian politicians, Eduardo Suplicy, with recognized militancy on the left, the objects of insults and disrespect from the bloodthirsty mob. What happened was an act of unacceptable intolerance, not only against an supposed “CIA agent” blogger, as they wanted to see it, but an attempt by a foreign country (the Cuban government) to define the course of internal policy South American giant.

following presentations had the simple and only objective of hearing what she had to say about a wide range of topics, all focused on an island greatly loved by Brazilians of all stripes: Cuba. After that first night of intolerance, overcome by the courage of the blogger and the support of senator Suplicy, Yoani was offered dinner at the residence of one of the organizers of the activities in the city, where the Cuban blogger shared the evening with Senator Suplicy, an important participant in the acts of that day, founder and leading member of the Brazilian Labor Party, as is well-known. Yoani and Suplicy spoke at length.

following presentations had the simple and only objective of hearing what she had to say about a wide range of topics, all focused on an island greatly loved by Brazilians of all stripes: Cuba. After that first night of intolerance, overcome by the courage of the blogger and the support of senator Suplicy, Yoani was offered dinner at the residence of one of the organizers of the activities in the city, where the Cuban blogger shared the evening with Senator Suplicy, an important participant in the acts of that day, founder and leading member of the Brazilian Labor Party, as is well-known. Yoani and Suplicy spoke at length.

My trip to Prague is funded by Amnesty International, because I was invited as a juror for a film festival they organized. I will go to Italy to collect an award that I had not been allowed to collect, which included–at that time–the plane ticket. From Italy I will go to Spain for the El Pais award, which also includes airfare. From Spain I go to New York, by invitation of students from two universities, which offer courses on computer science. From NY I will go to Miami to visit my sister, with airfare paid for with her money. From Miami I am going to Mexico to a meeting of the Inter American Press Association, IAPA, of which I am vice president (an office without pay, which Cuban propaganda reported erroneously) but they did pay for my ticket.

My trip to Prague is funded by Amnesty International, because I was invited as a juror for a film festival they organized. I will go to Italy to collect an award that I had not been allowed to collect, which included–at that time–the plane ticket. From Italy I will go to Spain for the El Pais award, which also includes airfare. From Spain I go to New York, by invitation of students from two universities, which offer courses on computer science. From NY I will go to Miami to visit my sister, with airfare paid for with her money. From Miami I am going to Mexico to a meeting of the Inter American Press Association, IAPA, of which I am vice president (an office without pay, which Cuban propaganda reported erroneously) but they did pay for my ticket.

From the VIP lounge we were taken, through the interior hallways of administrative offices of the Recife airport–for fear that the conventional hallways of the airport would be full of demonstrators paid for the by Cuban embassy–to the operations room of the airline that would take us from Recife to the city of Salvador, capital of Bahia State, the stage for the first public appearance of the famous Cuban blogger. The operations room of the Brazilian airline was little, enough for a few work tables, communication equipment and computers, where we were “treated like royalty” by the business’s operations workers, who offered us the use of their facility. Yoani, who had brought her laptop from Havana, hurried to access the Internet, surprised by the speed of the connection, navigating, rapt.

From the VIP lounge we were taken, through the interior hallways of administrative offices of the Recife airport–for fear that the conventional hallways of the airport would be full of demonstrators paid for the by Cuban embassy–to the operations room of the airline that would take us from Recife to the city of Salvador, capital of Bahia State, the stage for the first public appearance of the famous Cuban blogger. The operations room of the Brazilian airline was little, enough for a few work tables, communication equipment and computers, where we were “treated like royalty” by the business’s operations workers, who offered us the use of their facility. Yoani, who had brought her laptop from Havana, hurried to access the Internet, surprised by the speed of the connection, navigating, rapt.

The principal activity for which Yoani had been invited to Brazil was the presentation of the documentary “Connection Cuba-Honduras,” by the Brazilian filmmaker Dado Galvão, in Bahia and specifically in the city of “Feria de Santana.” The event was programmed for 7:00 in the evening of the day of Yoani’s arrival, and was to include the participation of the Brazilian senator Eduardo Suplicy, founder of the Labor Party (PT), the party to which ex-president Lula da Silva and the current president Dilma Rousseff belong. On being advised that Senator Suplicy had arrived at the presentation hall of the documentary, we left the hotel in the minibus and headed to the first public activity scheduled during her visit.

The principal activity for which Yoani had been invited to Brazil was the presentation of the documentary “Connection Cuba-Honduras,” by the Brazilian filmmaker Dado Galvão, in Bahia and specifically in the city of “Feria de Santana.” The event was programmed for 7:00 in the evening of the day of Yoani’s arrival, and was to include the participation of the Brazilian senator Eduardo Suplicy, founder of the Labor Party (PT), the party to which ex-president Lula da Silva and the current president Dilma Rousseff belong. On being advised that Senator Suplicy had arrived at the presentation hall of the documentary, we left the hotel in the minibus and headed to the first public activity scheduled during her visit.

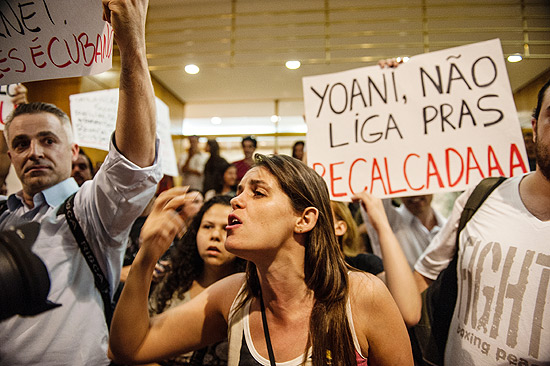

With me hugging Yoani against the side wall to protect her from the crowds, we headed out, to almost no shouts, to a table arranged at the front of the audience. The table was improvised from several plastic tables pushed together, and we sat behind it, Senator Suplicy in the middle, on his right Yoani, I on her other side and Dado Galvão next to me. The audience consisted about 50 Brazilians interested in seeing the documentary and meeting the blogger, all seated, and about 15-20 demonstrators, all standing, shouting slogans from the early days of the Revolution. Suplicy took the floor and immediately gave the microphone to Yoani.

With me hugging Yoani against the side wall to protect her from the crowds, we headed out, to almost no shouts, to a table arranged at the front of the audience. The table was improvised from several plastic tables pushed together, and we sat behind it, Senator Suplicy in the middle, on his right Yoani, I on her other side and Dado Galvão next to me. The audience consisted about 50 Brazilians interested in seeing the documentary and meeting the blogger, all seated, and about 15-20 demonstrators, all standing, shouting slogans from the early days of the Revolution. Suplicy took the floor and immediately gave the microphone to Yoani. Yoani stood up and said that she had no fear of submitting herself to questions (alluding indirectly to her lack of fear of the demonstrators), that if this was a demonstration of democracy she was willing to accept it; she spoke about the similarities of Cubans and Brazilians, talked about her blog and other general aspects, giving the protestors the floor to ask questions. Yoani’s security was very precarious in these circumstances. There was a plastic table between her and the enraged demonstrators, standing less than a yard away, such that physical aggression would not be difficult. I asked Yoani to move her chair as far back as possible, where there were bodyguard police.

Yoani stood up and said that she had no fear of submitting herself to questions (alluding indirectly to her lack of fear of the demonstrators), that if this was a demonstration of democracy she was willing to accept it; she spoke about the similarities of Cubans and Brazilians, talked about her blog and other general aspects, giving the protestors the floor to ask questions. Yoani’s security was very precarious in these circumstances. There was a plastic table between her and the enraged demonstrators, standing less than a yard away, such that physical aggression would not be difficult. I asked Yoani to move her chair as far back as possible, where there were bodyguard police. They begin with the typical charges. That Yoani was a member of the CIA, that she hadn’t expressed herself about the “blockade,” nor about the prison in Guantanamo, nor about “the 5” Cuban spies imprisoned in the USA. They asked about origins of the resources for her extensive international travel, among other things. The demonstrators–all of them–had a paper printed in color, probably by the Cuban embassy, with the written “directions” to the slogans and the accusations being made against the Cuban blogger.

They begin with the typical charges. That Yoani was a member of the CIA, that she hadn’t expressed herself about the “blockade,” nor about the prison in Guantanamo, nor about “the 5” Cuban spies imprisoned in the USA. They asked about origins of the resources for her extensive international travel, among other things. The demonstrators–all of them–had a paper printed in color, probably by the Cuban embassy, with the written “directions” to the slogans and the accusations being made against the Cuban blogger.