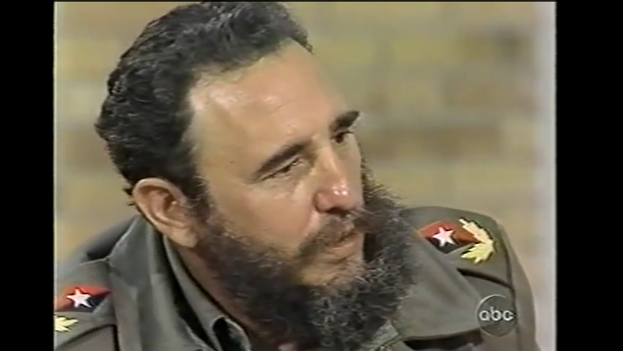

![]() 14ymedio, Jose Gabriel Barrenchea, Holguin, 15 August 2015 — For many, Fidel Castro has been “a light in the street and darkness at home.”* Although I don’t believe that either outside or inside Cuba’s borders this gentleman has illuminated a new path for humanity, I have to admit there is some truth in such a vision of his role in history. More than with doctors and teachers, Fidel Castro has performed an invaluable service for Latin Americans, behaving like those knuckleheads in the classroom who practice the sport of attracting to themselves the wrath of the teacher.

14ymedio, Jose Gabriel Barrenchea, Holguin, 15 August 2015 — For many, Fidel Castro has been “a light in the street and darkness at home.”* Although I don’t believe that either outside or inside Cuba’s borders this gentleman has illuminated a new path for humanity, I have to admit there is some truth in such a vision of his role in history. More than with doctors and teachers, Fidel Castro has performed an invaluable service for Latin Americans, behaving like those knuckleheads in the classroom who practice the sport of attracting to themselves the wrath of the teacher.

Many countries in Latin America, if not all, have benefited at some point from the role assumed by Fidel’s Cuba against Washington. They only had to sit at a desk and assume the face of an exploited lamb while the fractious Caribbean big guy assumed the defense of their rights with equal or more fervor than they themselves.

What’s more, in this role, the merit belongs not to Fidel Castro himself. It is unquestionable that he has been the first and only Latin American leader who has seriously challenged the hemispheric hegemony of the United States. But he achieved it for no reason other than the fortunate circumstance of having been born in Cuba. In short, the only merit of the Revolutionary Fidel Castro was to have been carried away by the explosion of expansive nationalism that this people of extremes experienced in the middle of the twentieth century.

However, as a revolutionary or as a tyrant, it is indisputable that Fidel Castro has truly brought about a dense darkness “in our house.” It is quite possible that only Captain General Valeriano Weyler was more disastrous for Cuba than what has resulted from this offspring of one of the little soldiers Spain sent here to fight against the desire of our ancestors to be free and independent.

Fidel Castro’s refusal to act For example, his refusal to act as a politician, that is with responsibility, put the country at the edge of the abyss during the missile crisis, in October of 1962.

For example, his refusal to act as a politician, that is with responsibility, put the country at the edge of the abyss during the missile crisis, in October of 1962. Indeed, one can admire and be proud of the fortitude with which the Cuban people faced the threat of nuclear holocaust, however frightened they were and opposed to the way in which their leader was stubbornly dragging it towards them. Nor did he channel in realistic ways the explosion of Cuban vital energy of the mid-twentieth century. Fidel Castro behaved not as a hero, but was a huge disgrace to his countrymen.

On assuming power in 1959, Fidel Castro took over a country that needed to find a new base of economic to assure the level of prosperity previously — but no longer — enjoyed, that had been shared out, with its vagaries, for more than a century. Since 1926, more or less, the Cuban economic model. based on the production and export of huge quantities of raw sugar, was in crisis. Such was the magnitude of this crisis, that from that year productive investments were not realized in the sugar industry. Despite the general will of the nation to improve the living standards of all its members, it was impossible to do so in the case of farm laborers. As would be shown in the sixties, it was absolutely unsustainable to increase the wages of the manual cane cutters, without destroying the profitability of the entire sugar industry.

After achieving full national sovereignty in the Revolution, it was a fundamental duty of the new rulers to put Cuba back on the path of prosperity.

However, Fidel Castro, in his nearly half century of governance, did nothing realistic with respect to it. Absolutely unable to deal with complex and non-linear economic problems, he always thought that, as on any feudal estate in his native Birán, the omnipotent will of the owner was enough to advance a modern economy of the then not insignificant size of Cuba’s.

Fidel always thought that, as on any feudal estate in his native Birán, the omnipotent will of the owner was enough to advance a modern economy of the then not insignificant size of Cuba’s

Ultimately, his solution was not to convert the sugar industry into a modern sugar-chemical complex, as Ernesto Guevara had dreamed in the early sixties. Fidel Castro, pathologically incapable of doing anything good in economics, decided call on that other field that he seemed to give himself to so well: politics. If Fidel’s Cuba has experienced anything, at least from 23 December 1972 until today, it has been the economic exploitation of a dispute with the United States, more or less exacerbated any time it suited him. How? By presenting himself as the ideal ally of everyone who, in a world fill of such characters, had some ax to grind with the Americans.

By not solving the principal economic problem he just exacerbated the main danger to the nation: the lack of an non-precarious economic base that would assure credible levels of prosperity in a nation that had previously enjoyed a fairly high standard of living. Combined with very close proximity and easy communication with the United States, 1950s Cuba was in the same situation as a small planet that gets too close to an extremely massive one, ending up shattered into pieces with its remains devoured by the giant.

It was already clear in those years that, with no solution to its economic base, the nation would confront in the ‘60s and ‘70s a massive exodus of Cubans to the United States. Without any perspectives of work that would assure them the level of prosperity of their grandparents, or at least one that would compare to the neighbors to the south, there was no doubt that many Cubans would end up leaving with their families for the US. On the horizon, in addition, was the fear of the possibility of a resurgence of the previously overcome tendencies to desire Cuba’s annexation to the United States.

As would be expected in someone so impetuous, a Fidel Castro was caught flat-footed on the economic problem and tried to attack the danger directly… and to extract some advantage. As a leopard doesn’t change its spots, he tried to politicize it.

Those who left Cuba were businessmen, doctors, technicians, artists and generally a contingent of people with the values, skills and knowledge necessary to build a modern and prosperous society.

In a complex feedback process, Fidel Castro exacerbated the internal differences to the same extent that an ever greater human contingent continued what was already in the 1950s a natural tendency of Cubans to move. By 1965, a tenth of the population had emigrated to the United States, a human capital that few nations in the world of that era would have been able to display. Businessmen, doctors, technicians, artists and generally a contingent of people with the values, skills and knowledge necessary to build a modern and prosperous society.

After that, in the 1960s, we lost the sector of the population with the least affinity to his absolute authoritarianism, and he established immediate and complete control over the movements of the citizens who remained. Anyone, even the most humble seller of lollipops without any special knowledge or skills for national development, needed the express authorization of the Castro regime authorities in order to emigrate.

And at first it was almost impossible to get, at least until the eighties. Beginning in that decade Fidel Castro, by the confluence of many factors, increasingly relaxed his immigration policy. The main reason was the growing unrest.

Under his government, he had created a technical and professional sector much larger than the needs of the island. A large sector that found no possibilities for personal fulfillment in a country that first experienced the gradual withdrawal of the Soviet aid, and later its total disappearance. An extensive new opposition anticipated on the horizon, against which he might appeal to violence, although certainly not with the expected results, because already the international context wouldn’t support it. Alternately he could dip into the old standby of opening the path to emigration. Thus, this became the Cuban substitute for the Soviet gulag. Those who didn’t get on well in His Cuba could emigrate, or at least he was hoping they would, and this neutralized any desire they might have to fight.

The result of the total politicization of the life of the Cuban nation could be evaluated as of 31 July 2006. The day that, though he himself did not yet know it, Fidel Castro left power forever.

The result of the total politicization of the life of the Cuban nation could be evaluated as of 31 July 2006. The day that, though he himself did not yet know it, Fidel Castro left power forever.

By then, Cuba was (and is) without an economic base, no longer like that prior to 1926 with regard to a level of assured prosperity, but also one that brings some possibility of something more than survival to the absolute majority of the Cuban people. Even the sugar industry, with a respectable capital of accumulated knowledge of more than two centuries of evolution and with so many possibilities in new times, was eliminated by Fidel Castro in 2002. He tried in this way, it seemed, to avoid that on his departure from power, someone would dare to try to exploit the production capacity for biofuels.

But it is in the exacerbation of the danger to the survival of the nation, provoked by this lack of a non-precarious economic base, where we discover the darkest legacy of the half-century of the absolutist government of Fidel Castro. This, paradoxically, stands out still more, because Fidel Castro always presented his absolutism as indispensable to the survival of the “homeland.”

Fidel Castro’s regime has promoted the desire to escape from the island on such a scale that today, despite the enormous difficulties in doing so, almost a quarter of Cubans live outside of Cuba. What’s more, the principal danger in this is not in the proportion, but in the particular pattern of the Cuban migration with the flight of those people who are most educated.

Fidel Castro’s regime has promoted the desire to escape from the island on such a scale that today, despite the enormous difficulties in doing so, almost a quarter of Cubans live outside of Cuba.

From a Cuba in which initiative was a highly suspicious quality, and therefore under close surveillance by the secret police, the best prepared have necessarily emigrated, the most active, those least given to respecting the opinions of authority. In other words, the problem is not that emigrants are a quarter of the population, but that this quarter has been systematically selected to rob the nation of its members most likely to put themselves forward and lead a prosperous future, and an orderly one… democratic of course.

As this pattern of emigration continues, and even has even intensified since Fidel Castro left power, though his regime continues, it is not so fanciful to suppose that in the near future we might see Cuba converted into the most backward and poor nation in the western hemisphere. A position it is not far from today, despite the fact that in 1959 this same society only yielded to the United States and Canada and was equated with Argentina and Uruguay.

The damage Fidel Castro caused the nation has, in the end, been so great — a nation where in the 1950s there were only inklings on the horizon — that today there is a strong current of furtive opinion, although not openly expressed by hardly anyone, that suggests the only solution to the problem of having a country without an economic base is to annex the island to the United States.

This current, expressed only in private, remains dormant only because of the fact that the Castro regime’s propaganda still manages to be somewhat effective in promoting nationalism. However, it is to be expected that a nationalism without an economic base, or one in which the remittances of those who emigrated to the United States rapidly occupy this role, will end up eventually losing any prestige among ordinary Cubans.

The main legacy of Fidel Castro is precisely this: Never before have Cubans had less confidence in ourselves and, consequently, never has the idea of annexation had so many followers.

*Translator’s note: “Candil de la calle, oscuridad de la casa” (a light in the street, darkness at home) is a common Spanish expression meaning that a person is effective (“lit up”) away from home and with others, but useless (“dark”) at home.