Download the PDF in Spanish here: VOCES 17 PDF

English Translations of Cubans Writing From the Island

Download the PDF in Spanish here: VOCES 17 PDF

This past Sunday, July 22, Cubadebate, the Cuban Communist Party’s digital page Cubadebate published a police blotter style note in which was reported an auto accident in the eastern city of Bayama, which an individual of the name Oswaldo Payá Sardiñas, “resident of Havana,” had lost his life. This was all the information Cubadebate offered to it readers. Not even on the day of his death could the Cuban government concede to Payá the rank of dissident or opponent.

A few hours later, on the Facebook page of the same Cuban Communist Party, there appeared a doctored photo of Payá in which instead of holding the portrait of Orlando Zapata Tamayo, also an opponent who died on a hunger striker in 2012, there was a sign that said “Oswaldo Payaso” (Oswaldo Clown), and above an identification of the Catholic leader as “gusano” (worm). These epithets evidenced what the Cubadebate note did not say — out of hypocrisy more than reality — which was that Payá was not a dissident nor an opponent, but a “worm” and a “clown.”

Payá showed a tenacity and consistency unusual within the Cuban opposition. Since the late 80s, when he created the Christian Liberation Movement, he proposed to peacefully defend the freedoms of association and expression for all Cubans, supported by the laws of the Socialist State itself. More than a decade later, in 2002, he presented to the National Assembly of People’s Power an initiative signed by 11,000 people demanding a referendum and constitutional reform.

That citizen demand, which was protected by the Constitutions of 1976 and 1992, was ignored by the authorities. In response, the government mounted its own initiative, which established the “irrevocable” character of socialism and entrenched still further the criminality of the opposition. The Varela Project gave Payá an extraordinary international visibility, which resulted in the award of the Sakharov Prize by the European Parliament in 2002. In the spring of 2003, most of the members of his organization were imprisoned. Seven years later they were released in exchange for exile in Spain.

When an opponent dies, in any democracy, they put aside hatred and respect the dignity of the deceased. In a dictatorship like Cuba’s this doesn’t happen. The death of Payá has been grossly celebrated in various official Cuban media. Behind this irrational behavior lies the moral insecurity of those who cannot admit that an honest person, convinced of his ideas, would defend them with peaceful methods and within their own existing laws.

Originally published in La Razón. Reprinted in the independent digital magazine VOCES No. 16.

Your last name lends itself

to jokes of the kind that Cubans

are masters of

but you, luckily,

are the opposite

of your last name,

the jokes,

and what’s more important,

everything that smells of dogma,

eternal socialisms

and redundant death,

collecting the signatures

that will unveil

the tomorrow

that won’t be long.

—

Translator’s note: Payá sounds like “pa’llá” which is a very Cuban contraction of “para allá,” and is part of the phrase “pa’llá y pa’cá (para acá)” which translates as “coming and going.” A Miami based radio personality who opposed Payá used the phrase “Ni pa’llá ni pa’cá” (neither coming nor going) to refer to him and the Varela Project, which Payá founded, led and gathered signatures for.

—

From the digital independent magazine Voces (Voices) No. 16, which is an issue in tribute to Oswaldo Payá

“El dossier tratará de tener cierto rigor academic…” (The issue will have a certain academic rigor…) he writes. But my interlocutor – a word I had never personally spoken or written in my life BC, Before Cuba – my interlocutor knows me well; from you, he continues, from you “sería genial contar con una pincelada más jovial,” (and I have to look up “pincelada”… ahh, “brushstroke”). Yes, from me a brushstroke. A “more jovial” one.

OLPL knows me. His jovial pincelada proves it. We love each other. We have never met. I his mother’s generation, he my daughter’s. I see him walk, talk and pretend to be José Martí, machete waving wildly as he rides into battle on a make-believe horse near the backyard tap. I see the pixels of him. On my screen. I worry about him like a mother, like a friend. He doesn’t see me do anything (because, of course, he lives on the Island of the Disconnected), and he doesn’t worry about me because I live in a free country where we govern ourselves, and even if we are all insane our collective insanity is not a fraction of that contained, lurking, slithering around in the swamp, behind those sunken little button eyes of the Maximum Lunatic.

OLPL knows me. His jovial pincelada proves it. We love each other. We have never met. I his mother’s generation, he my daughter’s. I see him walk, talk and pretend to be José Martí, machete waving wildly as he rides into battle on a make-believe horse near the backyard tap. I see the pixels of him. On my screen. I worry about him like a mother, like a friend. He doesn’t see me do anything (because, of course, he lives on the Island of the Disconnected), and he doesn’t worry about me because I live in a free country where we govern ourselves, and even if we are all insane our collective insanity is not a fraction of that contained, lurking, slithering around in the swamp, behind those sunken little button eyes of the Maximum Lunatic.

A certain academic rigor. I like rigor. In my engineer’s mind. Things that add up. That can be measured, proven, seen, touched. I have no use for it, otherwise, this so-called rigor, in ordinary, or even extraordinary, human endeavor. I have made something of a career of pointing out that there is no rigor. I sneer at rigor. “Everybody knows” we say. But no one knows, most of what we know is just flat out wrong. (Although we do know the world is not flat.) And we never ask the right questions. We only ask questions whose answers tell us nothing we need or want to know. “Everybody knows,” they say, but in fact they, we, know nothing.

Certainly nothing that will explain the Maximum Lunatic and the world he has created. Nothing that will explain whole lives lived in la-la land, suffered in la-la land, endured in la-la land. A bloody la-la land where the consequences are no joke.

So I care nothing for rigor. And caring nothing for rigor, I am free to do my work, my self-appointed task: To be a tiny bullhorn, a Lilliputian bullhorn magnifying sounds from a benighted island. To offer macabre proofs-of-life: blog posts showing the hostages holding up today’s paper, the machetes nearer or farther from their throats, depending. All depending on the Maximum Lunatic. The one we don’t care about, the one who is nothing to us, that one.

Ahh, but the hostages, they are everything. They catch me, hold me, I am hostage to the hostages.

The first one. The one who grabbed my ankle and has not let go. La flaca. “The one brave woman standing up to…” Rosa Parks and Joan of Arc in a skinny Cubana. But I saw right away, saw her, not Rosa, not Joan, not “the one.” And I worried about her, until a chocolate-loving priest assured me that her smile lights up the room, the sky, the whole Island,

The first one. The one who grabbed my ankle and has not let go. La flaca. “The one brave woman standing up to…” Rosa Parks and Joan of Arc in a skinny Cubana. But I saw right away, saw her, not Rosa, not Joan, not “the one.” And I worried about her, until a chocolate-loving priest assured me that her smile lights up the room, the sky, the whole Island, she is the happiest person, the freest person in Cuba. In Yoani’s living room is peace.

she is the happiest person, the freest person in Cuba. In Yoani’s living room is peace.

And then the flaca’s husband. I must learn to hear this troublesome language in which Reinaldo speaks, this language my eyes and fingers translate but that my ears resist, jealously clinging to their deafness in its presence. I must learn to hear this troublesome language so I can laugh, roar, get the hiccups and let the tears run down my face when he talks.

Claudia.

Claudia.

Claudia-I-am-afraid-of-everything.

Claudia-I-am-afraid-of-the-dark.

Claudia-sometimes-I-can’t-sleep-at-night-waiting-for-the-knock-on-the-door.

Claudia-but… but… but… but-at-some-point…

At some point you don’t conquer your fear you just put it aside, and act. And there is the video of Miss Scaredy Cat, screaming at some flinching stupid thug who is telling her she is not “qualified” to go to the movies, being counterrevolutionary scum and all.

Claudia and Ciro.  Ciro who taught me my new favorite song, with lyrics so short even I can remember them – “Estoy buscando una forma poética de expressar lo mal, lo remal, que me cae, Fidel Castro”* – as well as my second favorite, “Apagones importados,” and who makes me laugh just at the joy of him. The G-2 of him. (He’s a quintuple agent you know: G-2, CIA, KGB, Stasi, and… and… and…That’s why he’s so rich, they all pay him.)

Ciro who taught me my new favorite song, with lyrics so short even I can remember them – “Estoy buscando una forma poética de expressar lo mal, lo remal, que me cae, Fidel Castro”* – as well as my second favorite, “Apagones importados,” and who makes me laugh just at the joy of him. The G-2 of him. (He’s a quintuple agent you know: G-2, CIA, KGB, Stasi, and… and… and…That’s why he’s so rich, they all pay him.)

And some without names who have enough trouble without my listing them here, relating how they moved me, burrowed into my heart, made me want to fly to the Island with presents for their children, cool presents, Swiss Army knives.

Laritza, ripping my heart out, gorgeous, every word cutting like shards of glass through the fucked-upedness. I want to rescue her, I want to cry at her admission of the many times she’s considered suicide, so matter-of-fact, as if who wouldn’t, under the circumstances, this barely grown woman, this thousand-year-old woman, who needs no rescue, not from me, not from anyone, mother, wife, neighbor, citizen, future of the universe, future of Cuba, only to look at her, only to hear her, is to know it will all turn out well.

Laritza, ripping my heart out, gorgeous, every word cutting like shards of glass through the fucked-upedness. I want to rescue her, I want to cry at her admission of the many times she’s considered suicide, so matter-of-fact, as if who wouldn’t, under the circumstances, this barely grown woman, this thousand-year-old woman, who needs no rescue, not from me, not from anyone, mother, wife, neighbor, citizen, future of the universe, future of Cuba, only to look at her, only to hear her, is to know it will all turn out well.

Gorki. Watching him jump around – watching his balconazo of outrage at the permanent cameras mounted on poles to watch him – I can only marvel that his mother didn’t smother him when he was five just to have five seconds of peace and quiet in her home. But thank god she didn’t.

Luis Felipe. Luis and Exilda holding up the sky, holding up their children, their incredibly beautiful children who shine with their parents’ love for them, children who I know will grow up in a free country and who will vote, really vote, for their own president.

I promised no more than two pages. I’m running out of space. I’m not running out of friends. All these pixelated disconnected friends I’ve never met. Rigor be damned. I love you. I want to see you with my own eyes with only air between us and then no air, I want to touch you, hold you, hug you, to need no proofs of life, to feel life. To grab on and never let go, even when we let go.

I keep you in my heart.

Revista Voces / Voices Magazine No. 15 / June 2012

Note: The article in Voces was translated from this original in English

*”I am looking for a poetic way to express how much, how very very much, I can’t stand Fidel Castro.”

Only since March of 2008 have Cuban citizens living on the island been able to contract for cellphone service. Before that it was the exclusive privilege of trusted officials and foreigners living on or passing through the island. With the ingenuity that characterizes us, we managed to skirt such difficult obstacles.

It was not uncommon to see Cubans station themselves at the country’s tourist centers “on the hunt” for a tourist who would do them the favor of contracting for cellphone service. The fact that the service was offered only in the form of prepaid cards made the trick that much easier. The foreigner “showed his face” to the Cubacel official who demanded a passport from another country, and then left his Cuban “friend” with the greatly desired SIM card.

Fortunately, one of Raul Castro’s first reforms was to eliminate what was known as “tourist apartheid,” although he substituted something worst… not written in the fine print of the contract. That is the prohibitive prices that make cellphones in Cuba a service available only to the wealthy—or politically reliable—sectors of the population.

To translate the expression “prohibitive prices” into figures comprehensible to any earthling, let’s look at some examples. To do that, it is first necessary to understand that Cuba has two currencies. The Cuban Convertible Peso (CUC)—which is not actually convertible into any other world currency—is pegged to the U.S. dollar, but after the exchange fees is only worth about 90 cents. Many products in Cuba are available only in CUCs. The second currency is the Cuban peso (CUP), also called “national money” and this is the currency in which we are paid our wages; twenty-four Cuban pesos equal one CUC. The average monthly salary on the island is 350.00 Cuban pesos, or 14.50 CUC, about $13 U.S. The highest monthly salaries are the equivalent of about $20.

To send a text message from Cuba to a phone abroad costs one CUC. So a simple message of greeting to a family member in Madrid or Buenos Aires would cost the average Cuban almost seven percent of his or her salary. Translated to the average national wage in the United States (about $3,500 a month), this would be the equivalent of $240 to send one text message, meaning the average American worker could spend his or her entire salary to send 14 or 15 text messages a month.

As absurd and exploitative as this seems, it is possible in today’s Cuba because we live with a monopoly of a single, State-owned telephone company called ETECSA. Our “socialism with opportunities for all,” is actually a system that defrauds its clients who have no rights to demand redress. Many Cubans joke that the initials ETECSA stand for “We are Trying to Communicate Without Trouble,” rather than their real meaning: Public Telephone Company of Cuba.

Who on the Island can afford these prices? The answer is complex, but worth taking the time to explore: those who work in corporations where they receive a part of their salary in CUCs; those who receive remittances from a relative in exile; those who have shady black market businesses; those who demonstrate such ideological affinity with the government that they ascend to jobs “with subsidized cellphone included”; those who travel abroad as musicians, as superior athletes or as Cuban technicians on official missions; those who work for themselves in some profession that produces more income than state employment; and also those who can count on the support of a friend living elsewhere on the globe.

If none of these paths existed—some illegal and others ethically reprehensible—Cuba would be a mute island with regards to cellphones, a black hole of communication. Fortunately, we are not.

The high costs of cellphone service are intended to raise the greatest possible amount of that desirable currency that the Cuban government needs to survive. So every text message a Cuban sends overseas helps to finance not only the infrastructure—inefficient and unstable—of phone antennas, ETECSA offices and the tie-wearing functionaries and their secretaries, but also part of the official propaganda on TV, weapons that are bought for a war that never comes, and even snacks for the political police who keep an eye on the non-conformists.

In short, without realizing it, we are subsidizing our own chains, we send a text message and with it we feed the censor who reads it on the other end of the line and the bureaucrat who is ready to cut off our service if he thinks the words sent “threaten national security.”

What would you do in such a case? Would you let it go? Renounce it? Protest? Would you vegetate in the morass of non-communication, aware of living under a State that owns all the businesses and all possible words? Would you demonstrate your outrage in some public place? There is not shortage of us who would like to do the same!

But it turns out that you—in the case “we”—are trapped in material deprivation, in a system that condemns us to a cycle of survival and guilt any time we manage to fly a little higher. Many even claim that the high cellphone prices in Cuba aren’t just to bring money into the State coffers, but also to prevent the wider use of this tool.

With just 1.8 million cellphone users on an Island of 11 million people, it’s clear that we are bringing up the rear of the communication train in Latin America. What’s more, landline phones are also less common here, and many Cubans have never had a home phone—that heavy contraption with a rotating dial, instead of a gadget with a screen and keys. Can you imagine that scary technology? If so, you can understand the awe of Cubans who have a Nokia or Motorola or some other model that rings in their pockets.

Those who finally manage to carry that ringing with them everywhere feel themselves members of a “brotherhood” of cellphone customers, chosen by economic chance often unrelated to how hard-working or socially important a person is. So the next step after contracting for service in one of the offices with the long lines and half-asleep employees, is to take care—however you can—that the ETECSA monopoly doesn’t cut your service.

How can you manage that? Shut up, fake it, don’t talk about any difficult issues on the phone, definitely don’t talk about that “dirty” thing called politics. Every Cubacel user senses that their phone could be like the waiting room at the train station, where every ear is listening. And these are not the paranoid delusions of Cubans, it’s common sense in a country where official television plays the recordings of people’s phone calls—recorded without any authorization from a judge or a court—where one dissident is talking with another, a citizen sharing critical opinions, through the ether of cellular service.

Paternalism, the constant observance and presence of the State, gives citizens the impression that any step over the line is illegal. The cellphone—most of our compatriots believe—is a gift to us, not a service that we ourselves pay for. While using it we must observe the same ideological guidelines that we follow at our school desks, at our jobs in some official institution, on the bus owned by the only legally permitted bus company. This gadget that connects us to another, for the ordinary Cuban, is linked to the fear that one day the service will be cut off for stating a critical phrase or an opposing view.

And so you ask us why there isn’t a North African style revolution in Cuba? How will we call ourselves together if the barely 11% of the population that owns cell phones treats them like precious jewels, like luscious fruit obtained after much difficulty that could be in danger if used for civic activities. Can you imagine for one minute a Spanish 15M activist paying 69 euros for a single text message? Think about the Occupy Wall Streeters with no ability to send chain messages to others who share their ideas, because the telephone monopoly cut off their service. Think about the Chilean student activists without the ability to communicate their dissatisfaction through social networks. Comparing realities is a risky thing, but it also helps to understand the limitations, we face.

It all became more complicated after 2008 when numerous Twitter accounts began to be opened outside the bounds of the official institutions. First awkwardly, and then in fascination, several citizens began to discover the potential of 140 characters. It seemed something unattainable for us ordinary disconnected Internauts. Keep in mind that throughout the 42,000 square miles of the Island, there is not one office where a citizen can go to contract for home Internet. This is a privilege enjoyed only by foreigners living in the country (how symptomatic!), or by the most trusted local artists and functionaries.

Fortunately, many of do not agree with the ideological kilobyte divide and dare to buy access on the great World Wide Web on the black market, or at least to knock on the doors of some embassy that provides access to the web, knowing that the official propaganda will make us pay a high political price. Others dare to use even more creative ways to reach cyberspace.

But this little blue bird, this social network used by so many all over the world, flitters here in another way. While the great majority of Twitterers do it from a computer (with TweetDeck and other applications), here only a few enjoy this possibility. You can choose to access this service from an institutional connection, which inevitably involves ideological concessions, or to declare yourself a fugitive-Twitterer and do it however you can. On the latter path is the possibility of posting to Twitter from text messages, a service that brings this social network to those dispossessed of access to the web—meaning any individual located anywhere in the world has access to it.

From Lisbon to Sidney, anyone who has a Twitter account and a cellphone can update their status through text messages, although with the limitation of not knowing what others are writing or what themes are trending on the network. But it is an option.

If you choose to Tweet from the physical comfort of official institutions, on the other hand, the content will in many ways be conditioned on the ideological directives of those places. Let me be clear that I am not trying to characterize all those who use a State connection as “official bloggers or Twitterers”… Not at all! Because that would be to fall into the same definitional scheme maintained by government propaganda. Among those people, some escape from this straitjacket—maintaining Twitter accounts completely detached from social or political reality—with texts in the style of, “Hi, friends… how beautiful is the sun this morning… and have you ever seen such a gorgeous sea?”

Others are sitting in front of their official computers, salary included, precisely to crack down—on the Internet—on voices that criticize of the system. You don’t believe me? Why then, as soon as the workday comes to an end, do the “official voices” disappear? Why do so many of those who attack government critics not dare to show their faces and hide behind the protection of a pseudonym? Why is it that sometimes they publish information that could only have come from the political police? Haven’t you wondered why so many show up with the same nickname at the same time every day, as if they were directed, commanded “from above?” On Twitter the soldier leaves traces of his position. In the midst of this spontaneity of the social web, partisan positions are easily detected.

So to express yourself on the web, to be a Twitterer in Cuba, is inextricably intertwined with your pocketbook and your ethics… because we live in a country where not only are differences of opinion penalized, but prosperity is as well. Let’s suppose for a minute that you are a successful entrepreneur—a difficult thing to be in the midst of high taxes and the lack of a wholesale market, but still, let’s consider this utopian example—and we read the hypothetical stream of tweets that you generate. Most likely it’s limited to talking about the recipes you prepare in your restaurant, the lovely rooms you rent, or the incredible car repair service you provide. You will say little, very little or nothing, in the way of social critique. Because you know that by doing so you’d be risking your license for self-employment, for which you’ve already paid so much.

Since childhood, you were taught in school that every opinion running around in your head should stay right there, where no one will hear it or, perhaps, you will whisper it to a friend, or to your partner when your heads touch on the pillow. Why would you jeopardize your small daily survival and throw yourself under the enormous microscope of power? For a few simple tweets launched like a bottle on the sea into cyberspace?

I understand it, but I do not applaud this attitude… I’m sorry, I’ve already found my voice and I cannot go back to silencing it.

Let’s continue taking you as an example—don’t think you can get out of it—and conjecture that, despite your salary of $13 USD, or your meager earnings at your private snack bar, you won’t want to give up expressing yourself on the social networks. A friend undertakes the steps to connect your cellphone to Twitter, your brother lives in Costa Rica and promises to recharge it for you over the Internet so you can use it to publish text messages… and having been silenced for so long, you have a lot to say…

Once you start in on the exorcism in 140 characters, Cubacel follows up with some short disconnects of your service, and new faces start showing up in your neighborhood—lurking behind columns and under the stairs. Your friends no longer call your house because you have become a “cyber-warrior,” one of those they see on national television typing on a laptop while elsewhere on the screen a helicopter gunship hovers.

Take a deep breath. Clutch the cellphone in your hand and ask yourself if the same thing will happen to Twitterers who spend their days typing slogans. Will they also update their status from a cellphone supported by a family member in exile? Or, on the contrary, will they be able to enjoy one of those computers permanently connected to an Internet that never disrupts the kilobytes sent in convertible pesos?

You will then begin to understand—or you’ve already sensed—that the whole system is designed to make you feel guilty for having a cellphone, for maintaining a Twitter account and, especially, to make you decide not to use it to raise your small voice—singular and different—to be heard in the global village.

Meanwhile, your brother in Costa Rica is painted by official propaganda as an employee of the CIA, and the various readers who recharge your phone from time to time are practically Satan himself.

You’re in the middle of the room about to toss your cellphone off the balcony and call ETECSA to tell them to put their service where the sun don’t shine, but you stop yourself.

You’re not going to let yourself get sucked into the mentality of the oppressor, you’re not going to let the hand that offers you bits of damp birdseed make you believe that the cage is preferable to the risk of flying free.

From Voces 15 / June 2012

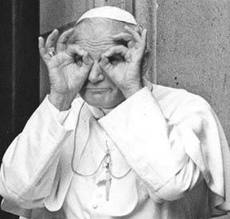

ON THE EVE of the arrival of John Paul II on the Island, almost fifteen years ago, an open letter circulated from “a certain Chicho.” As it was carefully conserved, we reproduce it here.

ON THE EVE of the arrival of John Paul II on the Island, almost fifteen years ago, an open letter circulated from “a certain Chicho.” As it was carefully conserved, we reproduce it here.

Open Letter to Karol Wojtyla, Pope John Paul II

The hardest thing for me is to address this letter. I don’t want to start with “Excellency” or “Your Holiness,” or put your first and last name, or your title of Pope. Since I don’t know how to do it, I apologize and will do it the Cuban way. First I have to speak to you in the familiar first person — with “tu” instead of “usted” — and second I’m going to familiarize your name. They told me in Poland they call you Tio Loleck, Uncle Loleck, but that doesn’t work here. For example, Ernesto Guevara we nicknamed “el Che,” Mikhael Gorbachov we called “el Gorbi.” and the Virgin of Charity herself, whom you will crown in Santiago de Cuba, between the threatening swords that point at the sky in Antonio Maceo Plaza, Her, we call her “Cachita.”

And so, meaning no offense, I name you “Woiti,” with affection.

The other thing I have to clarify for you is that people like me, who are around forty, we who were born in the Revolution, we have little occasion for religious faith; many of us have never been baptized because our parents wanted to join the Party, because that was where it always went best, but the Heart of Jesus always remained behind the wardrobe door, or there was a caracol under the bed, always, after that infallible “materialist cosmovision of the world” that they inculcated us with, we were left with a little doubt, it was our way to a little faith.

One day they held a Congress and religion was no longer merely “the opiate of the people” and you could be a militant Communist and a believer. Of course, that did nothing for those religious coming into the Party, but for those who were already in it, they could take off their atheist masks. With this end of the ideologies, many people were left with nothing to hold onto and they were thrown to their fate on this Island, and we had the joke that the most important thing is to have FE (faith), and the two letters of that word stood for Family in the Exterior.

ON THE EVE of the arrival of John Paul II on the Island, almost fifteen years ago, an open letter circulated from “a certain Chicho.” As it was carefully conserved, we reproduce it here.

Woiti, you have seen hunger worse than ours in other places in the world, you have known totalitarian repression worst than ours, religious persecution, massive exiles, lack of freedom, imprisonment, torture, lack of hope, crisis of values and many more problems, at levels so high that it might seem to a Rwandan, an Iraqi, a Guatemalan, or a North Korean that this is paradise; but these are our own and almost nothing we can do from within can relieve them. Fortunately you don’t represent a military power. As far as I know, the Vatican has never paid spies, nor engaged in terrorist, nor imposed a blockade, nor dropped bombs or bacteria on any place in the world.

So can I ask you to throw us a rope, and because you talk with Him, because he He receives you and hears you. Tell Him, that his flock does not want to continue to suffer, that we want to regain our individual dignity which we had to give in exchange for a national dignity that can only be seen for outside, in those solidarity clubs and in the headlines of our newspapers.

Hopefully we will not remember your visit only for the roads they fixed for your to pass along them, or because, perhaps, thanks to you, we will get to celebrate Christmas in a normal way again. Hopefully you will open a space with your presence. Hopefully He will hear you. Hopefully in your mouth our prayer is made audible.

Throw me a rope, Woiti!

This article is on page 53 of the Cuban independent magazine Voices 14, published 23 March 2012, in Havana, Cuba.

ALTHOUGH I AM a lapsed Catholic — a Catholic “my way,” as are almost all Cubans who claim to be one — I never denied it, in the time when the churches were closed or almost empty and the “tell me about your life” questionnaires had that famous question about whether you had religious beliefs. And I don’t regret it. Because, in these moments I feel I have the total right to say, unequivocally, that the attitude of the Cuban Catholic Church embarrasses me.

ALTHOUGH I AM a lapsed Catholic — a Catholic “my way,” as are almost all Cubans who claim to be one — I never denied it, in the time when the churches were closed or almost empty and the “tell me about your life” questionnaires had that famous question about whether you had religious beliefs. And I don’t regret it. Because, in these moments I feel I have the total right to say, unequivocally, that the attitude of the Cuban Catholic Church embarrasses me.

I can’t feel anything else after the — it was more than an authorization — the cardinal’s invitation, for State Security troops to enter the Church of Our Lady of Charity in Central Havana, and forcibly evict the thirteen dissidents — half of them women and old men — who occupied the temple for more than two days.

In reality, it wasn’t a surprise. After the Archbishop’s statement that seemed to have been written by a functionary from internal order in some prison, and specifically destined for the newspaper Granma and National Television News, we all expected a repressive outcome.

But it didn’t necessarily have to be that way. There are many ways to negotiate. I don’t believe the occupants were more rigid and intolerant and than the representatives of the regime. And look how well Cardinal Ortega ultimately arranged to deal with them.

But the Church hierarchy doesn’t have much patience or willingness to deal with dissidents. At least, that’s what Bishop Emilio Aranguren demonstrated over the last few days in forcing out, with screams and shoves, another group of dissidents in the Church of San Isidro in Hoguin. He warned that if they didn’t leave he would come with his people to evict them.

And it’s not that the priests shouldn’t be energetic when the time comes to respect the temples. But they shouldn’t exaggerate. Why, and to whom did Bishop Aranguren refer when he warned he would use “their people,” and “his people” to dislodge the dissidents. Perhaps the Church now has its own rapid response brigade?

Still and all, a priest who looks like a sheriff is preferable, as is the possibility of a para-police band of the pious and the charlatans, before inviting the political police to enter the temples to drag out a handful of peaceful people who just want their demands to be heard. Because that is what it was about, no matter how Cardinal Ortega’s spokesman, Orlando Marquez, claimed in a communication from the Archbishop that it was about “a strategy prepared and coordinate in advance to create critical situations” during Pope Benedict XVI’s visit. Or is that Orlando Marquez has at his disposal information about this, supplied to him by the comrades from State Security?

Those of us who consider these to be sites solely to pray to the Lord and for holy rites, and that they must be respected, do not approve of the method of occupying the temples. But far more insulting than the presence in the temple of those who mistake it as a stage for their protests, is the arrival of a police force, as disarmed as they say they may be. That Cardinal Ortega has invited them is even worse.

The Cuban Catholic hierarchy, and in particular Cardinal Jaime Ortega, is guilty of the gulf that has been created between the church and not just opponents, but most Cubans who aspire to live in freedom and who have no institutional spaces in which to express their demands. He is guilty, because he hypocritically and unilaterally takes on a mediation with the regime without defining what is proposed and for what purpose, creating expectations that he now does not know how to fill, much less have the courage to do so.

Will the Church be contented if the regime allows it to open seminaries, returns some of its confiscated property, authorizes a religious holiday and, from time to time, gives the Cardinal a few minutes on radio and television?

Should we not expect the Church to protect those who have no bread, the weak and the persecuted? Or is that, in Cuba, its social function will be limited to offering a little charity, giving courses for the self-employed, blessing the Economic and Social Guidelines of the Communist Party, and offering Masses for the health of Hugo Chavez?

Would they rather prefer the Church to cultivate good relations with the regime rather than with its long-suffering faithful?

Before a repeat of the occupation of another temple, or worse, it would be better if the Catholic hierarchy left hypocrisy aside and clearly defined where it is going and what it wants. And stop making (bad) policy. Or at least say for whom it makes it. To let it be known, once and for all — without any confusion — that it cannot be counted on for the cause of freedom.

the cause of freedom.

the cause of freedom.

the cause of freedom.

the cause of freedom.

the cause of freedom.

Luis Cino is an independent journalist and blogger in Cuba.

This article is on page 24 of the Cuban independent magazine Voices 14, published 23 March 2012, in Havana, Cuba.