Photo: Claudio Fuentes Madan

One of the new self-employment “activities” approved by the Cuban government is the controversial “recyclers-sellers of raw materials.” This toughest “private enterprise” encompasses Havana’s beggers who survive on collecting what the rest of the society throws out.

Several years ago Claudio Fuentes Madan was making a series of paintings using the city’s waste, which brought him into contact with many of these men and women who eat, literally, garbage. For the most part they are people without homes (and no possibility of acquiring one since buying and selling property is forbidden to Cubans). They spend the night in the most sinister places in the city (areas of destroyed hospitals, abandoned buildings declared uninhabitable because of the risk of collapse, parks far from the center, and that part of the urban landscape that is essentially shanty towns). They often live as “illegals,” under a Stalinist law that prevents anyone without a permanent address in Havana from staying in the city. To prevent disease, Claudio told me, they mix gasoline or kerosene into the water they use to bathe with, which they do at the home of an acquaintance, paying a modest rent in advance for the use of the sanitary services.

These are people who from now on will have to pay a percentage of their earnings to the Cuban state. It’s so sadistic it’s hard to imagine. You feel like covering your eyes with both hands like during the bloody scenes in terror movies. But this isn’t a movie, it’s what remains of the socialist economy.

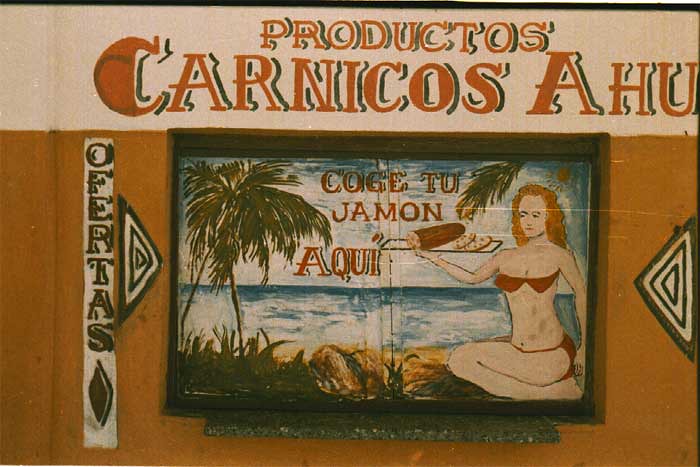

One wonders why this business appears to be — I can’t think of another adjective — prosperous enough for the State to decide to relieve its beneficiaries of a portion of their earnings. It turns out that true civics, that legendary course that my parents studied in primary school and I did not, has lost its semantic meaning in Cuba. People do not feel responsible for recycling the trash: if the state needs raw materials, that’s its problem. That’s why the recycling centers — the “offices for the recollection of raw materials” — are ignored; only the dumpster divers bother to take there the plastics and cans that they find in the garbage cans.

The other day a friend collected all the bottles that had accumulated in his home over the years, and set out — the paradigm of the New Man — to take them to the closest center. On arriving he discovered he had to take all his “recyclable material” home again, because he didn’t bring them in a sack consistent with what they would accept. Late that same night he gave them to a girl with a cart collecting rubbish in the city. She had changed her work schedule from three in the afternoon to three in the morning.

October 8, 2010