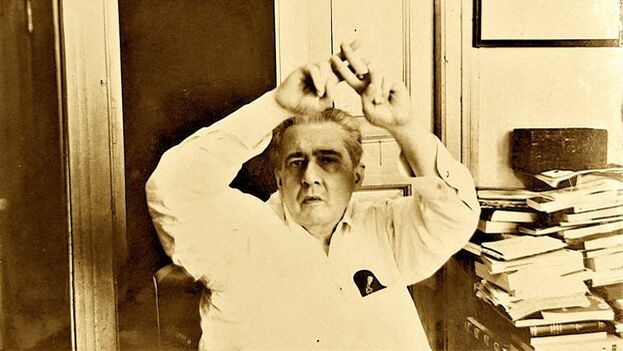

![]() 14ymedio, Xavier Carbonell, Salamanca, 2 January 2022 — In a calm voice, Ernesto Hernández Busto (Havana, 1968) says that, at the funeral of José Lezama Lima, an alleged spy filmed everything with a camera. The video, which no one has seen, must have been hidden in the secret archives of ICAIC [Cuban Institute of Cinematographic Art and Industry] or in a drawer of Villa Marista since that summer of 1976.

14ymedio, Xavier Carbonell, Salamanca, 2 January 2022 — In a calm voice, Ernesto Hernández Busto (Havana, 1968) says that, at the funeral of José Lezama Lima, an alleged spy filmed everything with a camera. The video, which no one has seen, must have been hidden in the secret archives of ICAIC [Cuban Institute of Cinematographic Art and Industry] or in a drawer of Villa Marista since that summer of 1976.

Lying on a tomb, with the apparatus on one shoulder, the unknown person recorded the faces of the mourners: Cintio Vitier, Ángel Gaztelu, Fina García Marruz, Raúl Roa, Ambrosio Fornet, Raúl Hernández Novás, Heberto Padilla and countless writers, officials, enemies and troublemakers.

From that moment on, says Hernández Busto, each of those present defends a different story about Lezama. Multiple anecdotes, opinions formulated at coffee time, plagiarized, misunderstood, distorted, forgotten and redone by his disciples. It is a complex region, in which the biographer always advances at his own risk.

Exiled in Barcelona, since the late nineties after several years in Mexico, Hernández Busto has been accumulating material for decades to write the first biography, in the strict sense, of Lezama. The book has become a kind of legend, and the author has only offered fragments to tempt the reader. Judging by these chapters — published in magazines such as Rialta, El Estornudo and Hypermedia — the Cuban project is cathedral, absorbing and does not even exhaust the Lezamian universe.

Lucid, Hernández Busto understands the magnitude of his commitment, in conversation with 14ymedio: “Whoever writes the biography of Lezama has to write, in reality, a history of Cuban culture, especially the republican one of the twentieth century. And perhaps also the history of a city: Havana.”

The problem is no different from that of those who established the canon of the sacred scriptures, speculates Hernández Busto. You have to face testimonies, contrast versions and sayings, consult multiple manuscripts, often apocryphal, as the evangelist Lucas does in El Reino [The Kingdom], the novel by Emmanuel Carrère.

“It is an unstable territory, because you have to differentiate gossip from history, always mixed with biographical anecdotes. A good example are the circumstances of his death and burial, told by various sources. That lack of definition turns any story into quicksand.” The writer also looks for the details, objects and evidence that give solidity to the text (such as knowing that Lezama’s funeral limousine was a 1959 Cadillac, a symbolic and ominous number).

“Moving between myth and exaltation is very uncomfortable, a constant doubt,” says Hernández Busto, who enjoys the challenge of collecting testimonies and detecting, after much research, who takes the right step in the labyrinth of versions. “The challenge is to make an English biography, more focused on the vital circumstances than on the works themselves; hence the provisional title: José Lezama Lima: a biography.”

The origin of this volume was a series of interviews he conducted, years ago and with a small recorder, with friends of Lezama, such as Father Gaztelu and José Triana. It was Triana’s wife, Chantal Dumaine, who provided him with several photographs of the burial where, in fact, the stranger appeared on the camera. “In a world of versions and assumptions, the discovery of a photo like this allows many things to be clarified,” he says.

Over time, the work grew in volume and difficulty. “A fundamental problem has been what to expose in the body of the text and what to place in the footnotes, which sometimes become small essays,” says Hernández Busto. The advances he has published attest to that temptation: with the secondary characters — the father, the mother, the sisters, the friends — another book could be composed.

To this must be added that it is intended to trace the biography of someone who distrusted the biographical exercise. “Lezama himself said: ’I don’t have a biography.’ He defended the autonomy of the literary work and repudiated Sainte-Beuve [whose critical method privileges the life of the author]. However, there are few more autobiographical books than Paradiso. That novel is a bit like the biography of a city, Havana, and a country, Cuba. Of course, in Paradiso, the biographical is recreated, used for a larger project, sublimated if you want. But all the scaffolding of the novel is deeply biographical,” he argues.

“The scarcity of biographies is a characteristic of the Cuban canon,” laments Hernández Busto, which is why he sometimes looks for neutral readers, outside the “Cuban world,” to evaluate the text. “Every time I finish writing a chapter,” he says, “I consult with friends, with people who met Lezama or lived during that time, but also with non-Cuban friends, who may have the perspective of a common reader. It is difficult to find the tone of the story while still being exhaustive.”

“If Lezama’s life is so interesting, it is because it includes two big unanswered questions,” Hernández Busto calculates: “Lezama and the Revolution, Lezama and homosexuality. Sex and politics. They are two great taboos, not only for this writer but for a culture and an era. Perhaps, after all, they are impossible to solve. But it’s worth trying.”

Translated by Regina Anavy

____________

COLLABORATE WITH OUR WORK: The 14ymedio team is committed to practicing serious journalism that reflects Cuba’s reality in all its depth. Thank you for joining us on this long journey. We invite you to continue supporting us by becoming a member of 14ymedio now. Together we can continue transforming journalism in Cuba.