![]() 14ymedio, Xavier Carbonell, Salamanca, 7 December 2022 — On 7 December 1990, 32 years ago, Reinaldo Arenas committed suicide “without first having to go through the insult of old age.” He himself recounts that, when they told him that he would soon die of AIDS, he went to his apartment and made a wish, half a prayer and half an insult, in front of the portrait of Virgilio Piñera.

14ymedio, Xavier Carbonell, Salamanca, 7 December 2022 — On 7 December 1990, 32 years ago, Reinaldo Arenas committed suicide “without first having to go through the insult of old age.” He himself recounts that, when they told him that he would soon die of AIDS, he went to his apartment and made a wish, half a prayer and half an insult, in front of the portrait of Virgilio Piñera.

“Listen to what I am going to tell you,” he snapped at the deceased, “I need three more years of life to finish my work, which is my revenge against almost the entire human race.” With unfortunate punctuality, three years after that sentence, and maintaining “equanimity until the last moment,” he killed himself in New York.

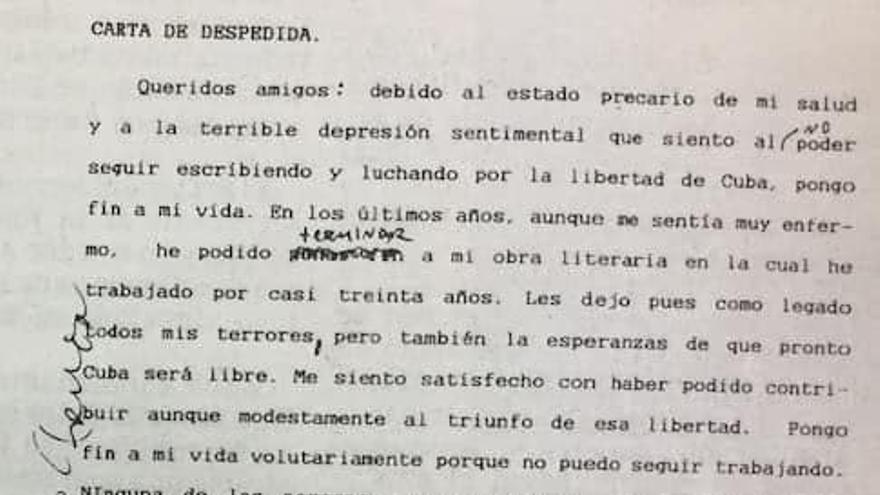

Of all Arenas’s texts, the most brutal and serene was his brief farewell letter, written to be published. “There is only one person responsible: Fidel Castro.” The phrase falls back on the Cuban reader, lapidary and current. “The sufferings of exile, the pains of exile, the loneliness and the illnesses that I may have contracted in exile, surely I would not have suffered if I had lived free in my country.”

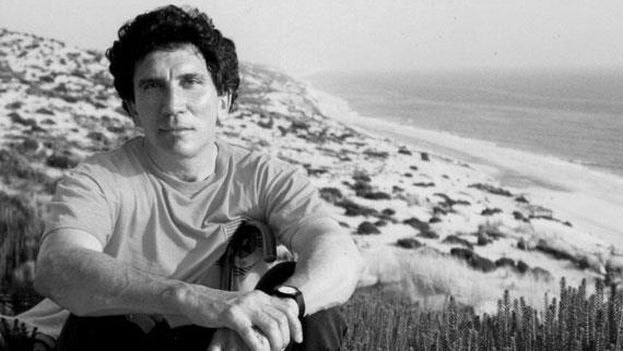

Arenas was born in 1943 in Holguín, a telluric and difficult region, from which Guillermo Cabrera Infante, Fulgencio Batista and Castro himself also emerged. Of Guajira origin, he always kept the rusticity and innocence of a boy from the provinces. Ruffled with hair and imagination, with a deep and seductive speech, the young man soon made his way in Havana and maintained a long friendship with José Lezama Lima and Virgilio Piñera.

His best-known book, Antes que anochezca [Before Night Falls*], attests to the surveillance, persecution, and imprisonment to which he was subjected by Castro’s political police. The cruelty of the State against the writer, the cornering of him in the most unusual settings – from Lenin Park to a precarious boat heading to the US – could only engender in Arenas a lucid, spiteful memory that was true to itself.

His novels – which he had to secretly send abroad – had already made him famous. But when a journalist traveled to Havana to interview him, he had to solve a labyrinth of clues and tricks, audacity and passwords, to find Arenas in the end, like a happy minotaur, in some dilapidated lot.

The succession of photographs that accompany Before Night Falls allow us to see how his face, mischievous in childhood, flirtatious in youth, and sad and sentimental about to board the boat in Mariel, becomes spectral and serene in 1990.

More than three decades after his death, the work of Reinaldo Arenas continues to be terra incognita for the majority of Cuban readers and almost none of his books are published in his country, thanks to the censorship of the same government that exiled him.

Reading El Mundo Alucinante [Hallucinations*] or Celestino Antes del Alba [Celestino Before Dawn*] clandestinely, enjoying the pages of La loma del ángel [Graveyard of the Angels*] or savoring his poems by the sea, continues to be the most endearing way to remember Arenas on the anniversary of his death.

*Translator’s note: The translated titles are not necessarily direct translations but rather those used in the English editions

____________

COLLABORATE WITH OUR WORK: The 14ymedio team is committed to practicing serious journalism that reflects Cuba’s reality in all its depth. Thank you for joining us on this long journey. We invite you to continue supporting us by becoming a member of 14ymedio now. Together we can continue transforming journalism in Cuba.