.

Occasional Photos by… / Orlando Luis Pardo Lazo

.

English Translations of Cubans Writing From the Island

.

He lost his high heels in the race. And the unprecedented tropical downpour, furious and fleeting, spoiled his vermilion make-up, which dripped from his pleated dress, staining the imitation leopard skin.

He lost his high heels in the race. And the unprecedented tropical downpour, furious and fleeting, spoiled his vermilion make-up, which dripped from his pleated dress, staining the imitation leopard skin.

The bright beam of a 400 watt light, focused intently from an idling police car, provoked a stampede of stunned homosexuals, caught red-handed in the middle of intercourse in a dark Havana park.

Cordoba Park, in the heart of the La Vibora neighborhood, has become a permanent plaza for discreet gays, scandalous transvestites and brave sodomites who do not believe in weather without the predictions of the Cuban Meteorological Institute.

That night, the guards in the patrol car are in a bad mood. STOP! they shout through a megaphone. The homosexuals disappear in seconds. But the transvestite on high heels can’t escape.

He tried running barefoot while holding his dress up. In his rush, he put his foot in a grating and got trapped. The cop, a black guy from Eastern Cuba, was fed up with the chase, completely soaked in the rain, and his military boots were full of mud. He looked at the anguished fag and screamed at him:

“Why are you running?! Maybe you committed a crime! You should have stayed put! Give me your identity card!”

The cop threatened to take him to the nearest police station. Trembling with fear and cold, his make-up smeared, in a barely audible voice, the transvestite answered:

“If you’re gay and a police car shines a powerful spotlight in the middle of having sex, the first impulse is to run. Things may have changed, but for a fag in Cuba, fear is always best.”

The two cops cut short the dialog. They frisked the transvestite and an imitation leopard skin wallet fell to the ground. Among the cosmetics something metallic and shiny rolled. A knife. It was the trump card for the nocturnal guards. “Now you’re fucked, faggot. Possession of a weapon,” they said, gloating, and handcuffed him without mincing words.

From their hideouts, the group of gays and sodomites watched the scene. Minutes later they returned to the gazebo in the unlit park, converted into the biggest homosexual inn under the open sky in Havana. This time, fear didn’t do their friend any good.

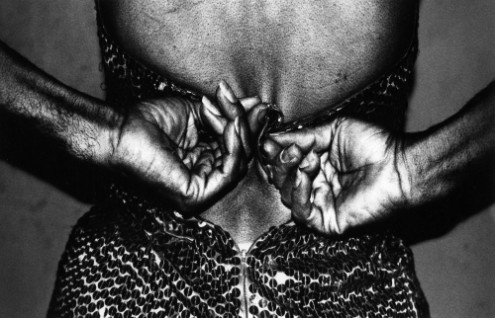

Photo: Cuban transvestite, by Marcello Bonfanti, AP. Word Press Photo 2005 Photo Prize.

23 January 2011

Timid colored awnings spring from nowhere and under newly opened umbrellas fruit smoothies and pork rinds are sold, while the doorways of some homes are turned into improvised snack bars with striking menus. All this and more is growing in the streets of my city because of the new flexibility for self-employment. Some of my neighbors are making plans to open a shoe repair, or a place to repair fridges, while avenues and plazas are being transformed by the efforts of private initiative. Some remain cautious, however, waiting to see if this time the economic reforms will really take hold and not be shut down as happened in the nineties.

Timid colored awnings spring from nowhere and under newly opened umbrellas fruit smoothies and pork rinds are sold, while the doorways of some homes are turned into improvised snack bars with striking menus. All this and more is growing in the streets of my city because of the new flexibility for self-employment. Some of my neighbors are making plans to open a shoe repair, or a place to repair fridges, while avenues and plazas are being transformed by the efforts of private initiative. Some remain cautious, however, waiting to see if this time the economic reforms will really take hold and not be shut down as happened in the nineties.

If it depended only on the political will of our leaders, we wouldn’t be experiencing in this awakening of citizen inventiveness. The Revolutionary Offensive of 1968, though long-ago, is still fresh in everyone’s minds; that time they expropriated everything that was left, down to the polishes and brushes of the shoeshine boys. But the liquidity and productivity crisis now facing the country has forced the authorities to take emergency measures, among them defining 178 areas in which people can be licensed for independent work.

We experienced a similar revival after the social explosion in August 1994, which came to be known as the Maleconazo — named after the famous seawall around Havana — where riots broke out. After that day, when discontent and frustration led thousands of Habaneros to head for the Malecon with sticks, stones and shouts, something changed in our lives.

We experienced a similar revival after the social explosion in August 1994, which came to be known as the Maleconazo — named after the famous seawall around Havana — where riots broke out. After that day, when discontent and frustration led thousands of Habaneros to head for the Malecon with sticks, stones and shouts, something changed in our lives.

The disturbance was quickly controlled by shock troops, but the defeat did not really fall on the disorganized and desperate groups who broke windows; the loser of that revolt was the Cuban government. Within a few weeks popular pressure led Fidel Castro to authorize something he detested even more than his neighbors to the north, the growth of small private enterprises.

He reluctantly allowed us to rent rooms in our homes to tourists, to take out licenses to drive private taxis, to create restaurants inside homes, and to offer our services as clowns at children’s parties. Soon, the face of cities and towns began to change. The fresh breeze of individual effort swept away years of state monopoly.

The ice cream made by those improvised merchants was much tastier than that from the State factory, the ham and cheese sandwich sold from the window of an apartment wasn’t adulterated like those in the State centers, and many foreigners preferred the warmth and kindness of a family restaurant over the aluminum and glass structures in the official hotels.

The new private entrepreneurs made it clear to us how centralization had lowered the bar of service quality, and they brought out traditional recipes we had almost forgotten. Despite the straitjacket and the high taxes imposed by the Ministry of Domestic Trade, despite the constant inspections and absurd prohibitions on selling certain products, many of these businesses were able to survive and grow. It required a thousand and one tricks o the part of the owners, but they could count on the complicity of their customers who — without any formal agreement — brandished the premise of “Pay for services from the self-employed before giving your money to the State.”

The new private entrepreneurs made it clear to us how centralization had lowered the bar of service quality, and they brought out traditional recipes we had almost forgotten. Despite the straitjacket and the high taxes imposed by the Ministry of Domestic Trade, despite the constant inspections and absurd prohibitions on selling certain products, many of these businesses were able to survive and grow. It required a thousand and one tricks o the part of the owners, but they could count on the complicity of their customers who — without any formal agreement — brandished the premise of “Pay for services from the self-employed before giving your money to the State.”

Then the regime was “rescued” by new financial support from abroad, coming not from the Kremlin this time but from Caracas. A petroleum-tinged embrace breathed new strength into the deteriorated government apparatus and prolonged the life of a dying system. Able to rely on an economic lifeline of this magnitude, the Cuban state lost interest in local entrepreneurs; yes, they were paying taxes, but they were making too much money and gaining ideological autonomy.

And so came the moment to close the tap: no new licenses were issued, taxes were increased, and new restrictions were created, each more nonsensical than the last. Hundreds of restaurants closed, they cracked down on snack bars, and only the strongest survived. Self-employment became a rare phenomenon in a society returning to total state control.

And so came the moment to close the tap: no new licenses were issued, taxes were increased, and new restrictions were created, each more nonsensical than the last. Hundreds of restaurants closed, they cracked down on snack bars, and only the strongest survived. Self-employment became a rare phenomenon in a society returning to total state control.

As they had done with the Soviet subsidies, our leaders squandered a good part of the Venezuelan resources on ridiculous campaigns and events of a political nature. Those petrodollars were used to shore up an already exhausted ideology, while the sugar industry fell into the deepest slump since early in the last century. Meanwhile, the mining industry was hit with low world prices, and services drowned in the diversion of resources — a polite name for manager and employee theft — and lack of quality.

Now that the time has come to prepare the accounts, the debts to other countries are enormous and the financial red ink foreshadows the collapse of the system itself.

So now it is time, once again, to rethink the forgotten national entrepreneurs who had successfully prevented the complete shipwreck of the Island once before. Raul Castro himself announced the expansion of the number of licenses available for self-employment, and for the first time he tied the word “irreversible” to these reforms. He even confessed that a false egalitarianism had brought us to this point. The straitjacket that gripped individual initiative seemed to loosen.

So now it is time, once again, to rethink the forgotten national entrepreneurs who had successfully prevented the complete shipwreck of the Island once before. Raul Castro himself announced the expansion of the number of licenses available for self-employment, and for the first time he tied the word “irreversible” to these reforms. He even confessed that a false egalitarianism had brought us to this point. The straitjacket that gripped individual initiative seemed to loosen.

The results are obvious. In just a few months we have recovered lost flavors, longed-for recipes, hidden comforts. More than 70,000 Cubans have taken our new licenses for independent work.

Despite the cautions from many, the still excessive taxes, and the absence of wholesale markets, small traders have started to raise their heads. You see them building their little stands, hanging colorful signs announcing their merchandise, rearranging their homes to accommodate a snack bar or a workshop. Most are convinced that this time they are here to stay, because the system is so suffocated it’s lost the ability to compete with them.

23 January 2011

BRILLIANT POST OF CLAUDITA CADELO, originally uploaded by orlandoluispardolazo.

It seems there are no eighth circles that put an end to this girl while, in the country of the pedantic and tantrum-throwing inter-llectuals, the camping literary Cuban continues to lose his last historic opportunity to speak of Cuba from a future perspective. Claudia, you go girl! You smoke all of them! Cuban writing will have to rely on your good bad-girl traits.

January 22 2011

Several anti-governmental signs appeared on the walls of official buildings January 17, in the Gardiola neighborhood in the municipality of San Miguel del Padrón.

On the “Panque Llave” bakery, located on Aleja between San Francisco and Dolores, one could read “Down with Fidel” and on the Food Warehouse, between 1º de Mayo and Circunvalación Streets, one could read, “They picked up the stallion to let the mare out*” an allusion to the brothers Fidel and Raul Castro. Several of the spectators predicted a public demonstration against the layoff measures being taken in the workplaces.

At each place there were Communist Party militants called to paint over the signs with dark paint, read out a statement, and sing the national anthem.

*Translator’s note: A more or less untranslatable and extremely insulting expression; the stallion is Fidel Castro and the mare is Raul Castro.

January 20 2011

Orlando Luis Pardo Lazo

Twenty years. Anniversary of the adversary.

Suicide in the winter. Suicide to win the marathon against the doctors and politicians (often indistinguishable) and also to kick his reading public (which did not exist then) to cuss it out twenty years later. In other words, today.

Suicide when beauty does not reach. Opening the mind when the brain no longer helps us to imagine our war in absolute freedom. To eject our delirium from our paranoia, the pamphlet and the plot. To put the rope around one’s own neck, the gun to the temple, or the soft palate (under the plastic prosthesis), to throw oneself under the train, rush the pills down the the throat, balance feet on the rough edge of the roof — not of Havana but of New York, the city that never sleeps away its nightmares while in the tropics we snore away our nap or our hangover.

To kill oneself in development. Annihilate one’s young and spirited self, whore with a furious desire to fornicate. Argh. With gonadtropical irrigation and damp intestines and semen to donate to the “heinous sinners” of the Third World, according to the Old Testament of the New Man.

To kill oneself without love. In a single bed. Not I, not yet. Another limited Cuban did it for me. He left the world in one go on December 7, a venereal Friday in 1990, while Cuba was about to dynamite its triumphalist discourse and impose another (no less despotic) to palliate the debacle: Special Period, War in Times of Peace, Option Zero, State of Exception, Death or Death, We Shall Overcome…

I’m talking about Reinaldo Arenas. The writer. The curse of mediocrity.

His death coincided with that of a mulatto not as brave as this little white guajiro. Anniversary of another shot to the temple that is celebrated even on the front page of the newspaper Granma. Antonio Maceo and olé, who didn’t care for traitors, poets nor faggots (often in distinguishable). And Reinaldo Arenas hit a trifecta. He was proud to inhabit these unowned wastelands, these unclaimed niches of our nation, this materialistic marginalia bordering the madness of ass whippings and lucidity. ARGH. Zen phallusophy.

Correspondingly, the Isle of Ill Will burned him. Cuba vomited out Reinaldo Arenas and neither the accomplice guilt nor the Cardinal saved him. His biography was the only thing that generated hate and envy (and the pain of those least known, like his mother). His work was the only thing that generates a spasm in the hands and eyes, an arched, “How did this son of a bitch to write so well?”

Reinaldo Arenas came from the future and he knew it. And he said it. The loneliness of his mission was self-imposed, because a wounded wolf cannot avoid vengeance even to see the blood flow (more than milk). There are spirits which crystallize anger and laughter, sweeping the rest of local literature that lacks it, dulled between court and court, among the hymns of a kamikaze comandate and the operetta or the tantrum of a key proletariat of a Revolution. Phooey.

He died on this day in 1990, no one around me remembers the anniversary of his suicide, with AIDS in the U.S. (this Friday the 10th my first 38 Decembers killed themselves). Nor can anyone of my generation name the exact title of a single one of his novels except Before Night Falls, which is not a novel but a lousy movie, not as cartoonish and Castroesque, and to make it worse I believe it was Made in Hollywood.

Personally, my soul rejoices. Reinaldo Arenas did not deserve to be part of academic curricula that classify all “isms” into themes. Reinaldo Arenas has earned for his tin drum (a lieutenant on horseback ate the bronze) the medal of national amnesia, a trophy better than the cultured and complacent appointment of a long-haired minister, or even worse, of the thousand and one good little girls with enough time and goodwill to get his doctorate at the cost of his original manuscripts and a library of exile. Grrrrr.

Reinaldo Arenas fell first that Cuba, like those gods displaced by brutes which are the clinical signs of the fall of the rest of their civilization. There is not Cuba after Him, no one should consider themselves deceived. His suicide as sacrificial, sacred. He sacrificed himself to imagine an island the congenital immunodeficiency of an impossible, or at least breathable, island.

His work is apocalyptic and accelerated as this column and, as such, naive. It was bigger than the wise. It was a rotten atrophied limb, chaotropic (mushrooms poisoned against the demagoguery of the dragon).

Today it has been twenty years and still there is not the least sign of his resurrection. Reinaldo, this is done (!!), when one is convinced in life to be immortal. Defeated by the mass for being immoral. Dry quicksand where you fermented your blood in this archipelago of swamps or the initials GULAG/UMAP.

Cubansummatum est!

(Forgive me, for your sharp planes of light like precious jewels. Reading is the eccentric experience of an ahistorical horror. All my text is photophobic.)

December 7 2010

Yesterday, while waiting outside the Supreme Court for the results of the hearing on the case of the Cuban Law Association versus the Minister of Justice, I reflected — in the original sense of the word — about my ups and downs since that distant August day when I was also waiting outside another court, that time for the results of Gorki Aguila’s trial.

I never would have imagined that a few months later my blog would appear, that I would speak freely into a microphone — for less than a minute, but it’s the intention that matters — that later I would have to defend my right to enter a movie theater, an exposition, a concert. I remember that dark afternoon of November 6 and the Tweet I sent, thanks to which State Security was robbed of its impunity as it kidnapped Yoani, Orlando and me. I think, again, about Reinaldo at 23rd and G, like in a Russian film where the hero sacrifices himself at the end, facing a primitive stomping horde. I saw the faces — always the same ones — of those who over these last three years have lent their hands to repression, their tongues to perjury, their souls to hatred, and I sensed their unease.

I am a pessimist. I refuse to think that things are going to change tomorrow so as not to be disappointed later, and I repeat, over and over, “Even if it lasts twenty more years, I will keep writing.” But suddenly I made out a long road of freedom traveled. Torturous it has been, to be sure, but not more so than the satisfaction of seeing the man who once dared to lead a repudiation rally condemned to sitting on a park bench talking like a robot on his cell phone, his hands that once served only to beat people useless, now, to this ogre faced with the power of words, the power of friendship and faith in a democratic Cuba. That repressor who once screamed in my face, “This street belongs to Fidel!” looked at me, at me and my friends, walking along Boyeros. He learned that the street no longer belongs to a delusional old man. Like it or not, it belongs to me, to him, to all Cubans, and we are obliged to share it.

22 January 2011

He bought a box of strong cigars though he doesn’t smoke, a cloth bag for errands, though he already had one, and two boring copies of Granma on the same day. He did it to help the trembling ancients with their bloodshot eyes who sell endless bits and pieces on the streets of Havana. People with legs stiffened by arthritis, hair gone gray years ago, a cane to complete their spindly anatomy. Old men and women thrown into the informal market exhibiting their meager goods in the doorways of Reina, Galiano, Monte and Belascoain Avenues. Septuagenarians forced to sell their constantly dwindling ration quotas, sad-faced grandmas who eat thanks to the candy and peanuts they themselves sell outside schools.

Thousands of Cuban seniors — at the end of their lives — have had to return to work, this time facing illegality and risk. Hands shaking with Parkinson’s offer sugary snacks at bus stops, wrinkled faces offer razor blades for only five pesos. Their pensions are extremely low and the well-deserved rest they planned to enjoy has turned into jittery days hiding from the police. The system they helped to build cannot provide them with a dignified old age, cannot spare them from misery.

That ungainly octogenarian, dragging his feet to the corner, hawks sponges to scrub with and tubes of crazy glue to stick everything together. A passing girl checks the contents of her wallet. She doesn’t have enough for either one, but in the morning she returns to buy something, if only one of those national newspapers in whose pages the faces of the elderly are always happy and satisfied.

January 22, 2011

I met Pedro Cruz Mackenzie when we were both taking university prep classes. It was during those difficult years which came to be known as the Special Period. In between classes we would entertain ourselves by collecting oranges, bananas, and any other source of food we could get to ease that hunger which was so common at that time. His academic talent and his skills for “sneaking” into math and chemical experiments earned him much fame in that place. Upon finishing the course, he was one of the recipients of a Medical scholarship.

Many years later, our paths once again crossed. He did not become a doctor, and he was not able to become a faculty member of any university. He soon grew tired of so much misery, of getting to class with ripped shoes, and of not counting on any real support to inspire him to study. He abandoned his strictness midway through his Cuban university career. Now, he clandestinely sells merchandise on the beach, he gets his hands on any souvenir that he can, trying to sell them in order to purchase clothes for his kids. Whenever the opportunity arises, he runs errands and delivers merchandise from one place to another.

However, he has also joined the struggle to denounce Human Rights violations in Cuba. While the police have him under constant watch, he denounces Cardet, the chief of the Police Sector in the neighborhood of Melilla in Santa Lucia, Holguin. Cardet is a soldier in charge of prosecuting disaffected youths, and Pedro tells me that, in conjuction with the president of the Committee for the Defense of the Revolution (CDR) of Yamagual, he has taken note of all those young people who “don’t want” to work agriculture or construction for 8 hour days for just 6 Cuban pesos. The officers claimed that such youths will shortly go to trial.

“I don’t have the list of all the names, with myself included,” Mackenzie tells me on some notes written on a yellowish paper, “some are too scared to give me their names. But as soon as I find them out, I’ll send them to you or tell you over the phone — you can be sure of that,” he concludes.

The thing is that my friend from back during the difficult years, Pedro Cruz Mackenzie, lives at the entrance of the Tourist Pole of Guardalavaca, in Holguin. This Pole is a special reserve for foreigners who decide to vacation in this area of Cuba. The strict police control, the lack of employment for those who are not trustworthy enough in the eyes of the regime to be able to work in their hotels, along with the sharp contrast in lifestyles between hospitality and tourism employees and those who do not have access to such currency or tips given by tourists is a very difficult and incomprehensible fact. “If something happens to me (he is referring to being jailed) please denounce the situation quickly so that my wife and kids can be visited by some of the Human Rights people,” that is one of the final phrases written in the letter by my friend Pedro, another one who has decided not to wear the shackles of this modern slavery.

Translated by Raul G.

January 21 2011

By Natalí Peguero Díaz

A teacher showed us very old photos of my town. None of us could recognize the majority of the places in them, although most were the most central of the town. Images of buildings such as la Casa de la Tertulia, the old wooden mansion that served for a long time as a school, stores and private businesses (as many as two or three in a single block), and the park with its gazebo that the grandparents miss so much.

Someone was impressed with the quantity of goods in a store, and the professor, one of those people who has a justification for everything, said yes, there were many things but they weren’t for everyone, those were bad times because the money didn’t stretch far enough to eat, but thanks to the Revolution everything changes. It’s true. Everything changed.

Today my town doesn’t shine as it once did. La casa de La Tertulia changed its name, and now sports a large sign that says, “in danger of collapse,” and all that is left of the old wooden house is the floor and an enormous vacant space that has been turned into a trash dump. Some of the old stores remain, of course, but only the old building, there’s no longer anything in them for anyone.

When I am a grandmother, I will also show the photos that I am taking now of my San Cristóbal and when my grandchildren ask, I will also tell them that things were bad.

San Cristóbal, Pinar del Río. b. 1992

January 20 2011

The Research Center on Aging (CITED), located in the Surgical Hospital Calixto García in the capital, conducted an analysis of the Economic Guidelines, at 3:00 pm on January 13, setting off an explosion of statements from the medical corps working there.

Once the introduction of the presentation was underway, Dr. Horacio Tabares, orthopedic specialist, interrupted demanding an explanation for the support and insufficient pay for the medical personnel working at this national center, “I need someone to explain to me why children over seven cannot have milk and why as doctors we have no right to breakfast unless it’s a sip of coffee, while we have to face five, seven and even eight hours of surgery where we are playing with human lives. When you explain these points to me, then we can go on to talk about the economic guidelines.”

Dr. Erick, a resident in geriatrics, commented on the lack of nursing personnel in the critical care ward, where the nurses work 48 and even 72 hours without any relief. He also asked why the menu consisted of peas and cornmeal every day.

The analysis of the document was delayed because the participants left the session.

January 20 2011

In the first half of the 20th Century and up to the decade of the seventies, December was a month of joy and January a month of hope. It was the beginning of the new year, in which we made resolutions to improve over the past, and in this effort, very humane and just, we always aspired to do better. The year that was leaving was represented by an old man with a scythe, and the one coming by a baby in diapers. It was the transition from the old to the new.

This allegory, for unknown reasons, hasn’t been used in my country for many years, and January has become a month of uncertainties, a month with a “jinx.” I don’t know if it’s planned or coincidence, but the bad news is always announced in January. This has dampened Christmas eve and Christmas, and their celebration is limited to the immediate circle in those families who persist in maintaining the tradition. Epiphany brings even worse luck. We can’t be happy in December when January is looming with storms in the forecast.

This year, to not break the chain, they have announced massive layoffs that will reach, in the first stage, one million two hundred thousand unemployed. These are not the official words used, but they’re the real ones. If this is what awaits us in the first month of the year, the rest doesn’t seem very hopeful. There are other measures, also announced, that will further complicate the survival of each citizen.

It’s a good thing that they’ve set aside the habit of naming the years and now they are only numbered by the number of years that have passed since the insurrectionists’ triumph. Otherwise, they would have had to call 2011 “The Year of the Unemployed,” or, perhaps, repeating past experience, “The Year of the Sixth Congress.”

Despite everything announced for January and the subsequent months, on the personal and family level we are healthy and have positive life projects for the new year on which we will focus our major efforts. This is the only way we can escape pessimism, and bring needed happiness into our lives, to survive this dark and closed reality.

January 5 2011

Since the last week of December, the Cuban news media turned the propaganda time chart on the 52nd anniversary of the Revolution, whose reviled founders stayed in power and in the disgust of the population, submerged in silence and the routine of a half-century of slogans and promises.

Since the last week of December, the Cuban news media turned the propaganda time chart on the 52nd anniversary of the Revolution, whose reviled founders stayed in power and in the disgust of the population, submerged in silence and the routine of a half-century of slogans and promises.

There was a Revolution but at these heights nobody remembers when it lost its way. Perhaps from 1961 to 1968, on eliminating private property, imposing the state monopoly on the means of production and adopting the tropical version of the Soviet model. Maybe in the middle of the seventies, on institutionalizing the socialist process, sending troops to the African wars and following orders from Moscow, whose regimen fell in 1991.

But it’s not necessary to highlight the matter, for January 1st isn’t any more than a date associated with an imaginary Revolution of Castro-communism; on whose legitimizing calendar other anniversaries of fighting actions are revisited, like 26 July 1953, evoking the failed assault on the “Moncada” and “Céspedes” barracks, which happened in Santiago de Cuba and Bayamo; and 2 December 1956, which commemorates the landing of the yacht Granma in the south of Oriente, considered afterward as Revolutionary Armed Forces Day, founded by decree in October of 1959.

For the past half-century they have been exaggerating the size of the traces of these events, of such indubitable influence in the country’s destiny, crammed down our throats by the attackers who prepared the ill-fated expedition of the Granma, whose survivors started the guerrilla focus which carried out the rural skirmishes of the so-called Rebel Army, one of the forces that fought against the tyranny of General Batista, who fled Havana at daybreak, 31 December 1958.

These facts, retold to the point of exhaustion by the historians and the government’s communication media, have as a common denominator the violence and the necessity of imposing the leadership of the manipulator, Fidel Castro.

To assault the barracks in the eastern zone of the country, the participants bought arms, practiced marksmanship in various places around Havana and crossed the island, besides risking the lives of people who were enjoying the Carnival in Santiago de Cuba, killing dozens of soldiers and exposing their own men. The failure complemented the adventure, but it is worth asking: What would have happened if they had taken it? If the idea was to climb the mountains, why didn’t they just do that?

To assault the barracks in the eastern zone of the country, the participants bought arms, practiced marksmanship in various places around Havana and crossed the island, besides risking the lives of people who were enjoying the Carnival in Santiago de Cuba, killing dozens of soldiers and exposing their own men. The failure complemented the adventure, but it is worth asking: What would have happened if they had taken it? If the idea was to climb the mountains, why didn’t they just do that?

If we leave behind the problems created by the attackers, the punishments after trial really were benign, the Castros and their followers only spent a year and a half locked up. On getting out, they went to Mexico “to prepare the insurrection,” instead of just climbing the mountains without spending on travel, yachts, fuel, nor violating the laws of a neighboring state.

Behind the expedition of the Granma, bought from the American Robert B. Erikson in Tuxpan with the money from the ex-president Carlos Prío Socarras (1948-1952), is hidden Castro’s proposed inscription in history of imitating the independence fighters of the 19th Century, who armed themselves in the United States and disembarked on various points of the island.

The map of their crossing reveals their irresponsibility and their headstrong nature. If they had left from the furthest point of Yucatan, in only hours they would arrive at the mountains of Pinar del Rio, closer to Havana, without having to cover almost all the Gulf of Mexico and the south of the island to the eastern end, the setting of confrontations just like the hills of Escambray, headquarters of the guerrillas of the Student Directorate, who defied the agents of tyranny in the capital and other towns in the east.

The legitimizing crowing comes to a head with the propaganda about the victory on that faraway first of January 1959, an anniversary that, paradoxically, is associated with the longest dictatorship in our history.

Translated by: JT

January 15 2011

Just less than eight years ago, in April of 2003, one of the most notable intellectuals of the Latin American left, Eduardo Galeano, published what he called, “Cuba Hurts,” about the wave of repression unleashed against dissidents, and in particular about the execution of three young men desperate to escape their own country.

It is impossible to synthesize in one short sentence such a symbolic and emotional charge.

To say that Cuba hurts, is to summarize in just two words a whole set of generally imprecise, ethereal sensations experienced by everyone who sees the reality of this narrow country not as something distant, like a Jurassic phenomenon that floats in the middle of the Caribbean, but rather as something very close to them. Or as themselves.

And today I have dusted off Galeano’s grim phrase because Cuba, again and again, hurts us. This journalist who until very recently lived there. And the news that comes to me from there sometimes arouses anger and sometimes laughter; at times it’s hilarious, or outrageous. But almost always, invariably, with maniacal precision, it ends in pain.

This time it comes in the form of an Official Declaration, and has the signature of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. They chose not to cross their arms and their hold their tongues, but came out shields in hand to defend the principles and precepts of the glorious Party, the ecumenical Revolution.

What is it now, the wrong they will right, the mess they will clean up? What is it this time, my friends? Well, very simple: It’s the pronouncement of Cuban diplomacy, with respect to the new measures just taken by the American government with regards to the Island.

Let’s see: 1. Authorize Americans to travel to Cuba for academic, cultural and religious purposes. 2. Allow American citizens to send remittances to Cubans in limited amounts. 3. Authorize international airports in the U.S. to request permission to operate direct charter flights to Cuba.

Has anyone noticed the most-repeated term in these three new measures? Authorize, Allow. The three offer new opportunities in different aspects; the three lift restrictions and prohibitions; the three are undeniably positive, although yes, it’s true, they are insufficient — seen through certain lenses — but they are undeniably larger and more satisfactory than all the measures taken by the government of the Island in its relations with the United States.

Ah, but no: Do not, ever, give an inch. This is not about recognizing positive things that come from Washington. Why? Can someone help me out here? Because it would disassemble the pyramid of lies on which the national and international policy of my country is built.

To say to Cubans, without snickering, that Americans only lifted the harmful barriers for people in the arts and sciences — thinking Americans — to visit their colleagues on the Island, was to move to the ideological ground of those who are indoctrinated to think of the gringos as the cause of every kind of tension in our land. Ergo, you would have to add the ominous tagline:

[The implementation of these new measures] “is an expression of the acknowledgment of the failure of U.S. policies against Cuba and a search for new paths to manage their historic objectives of dominating our people.”

And also:

“Though the measures are positive, they are far from satisfying the just demands, have a very limited reach and fail to modify anti-Cuba policies.”

To those who don’t understand why the triumph of Barack Obama lifted the veil of so many of the Castro-supporting politicians of my Island, to those who still refuse to lift a fossilized and ineffective embargo, there you have it: Barely a handful of timid, nearly-insignificant measures have put Cuban diplomacy on the defensive, stewing in its own sauce, while Uncle Sam gives no signals of goodwill.

When this happens, when the Unites States boasts of easing relations, they have to worry. And fight. They must be twitching, getting hives. No matter what it is: “If they ease travel restrictions for Americans we’ll scream about the blockade; if they lift the blockade we’ll scream about freedom for the Five Heroes; if they return the Five we’ll demand the return of Guantanamo Base; if they give us back the base… we’ll think of something.”

But there is one aspect these diligent strategists don’t take into account: our intelligence. The common sense of Cubans, on and off the Island — and it’s clear we haven’t been lobotomized — tells us, “Fine, it’s abundantly clear who wants to ease frictions and who wants to sustain them, no?”

Still, I have to admit, it’s not enough to coldly digest this Official Statement with ordinary patience. I declare myself incapable of it. I try to think in the spirit of Tibetans, who don’t read the newspaper Granma, and wonder if they have better methods of self-control. And I end up envying them.

But Cuba doesn’t only hurt, it also is humiliated. And it should be humiliating to every thinking, fair, honest human being who reads sentences like these from my belligerent country:

“The measures only benefit certain categories of Americans and do not restore the right to travel to Cuba to all American citizens, who continue to be the only people in the world who cannot visit our country freely.”

Tell me who doesn’t notice, please. Tell me who doesn’t feel embarrassed, who doesn’t feel the small sting of shame at the capacity for hypocrisy and political opportunism that the spokespeople for the government of this country appear to have.

It requires an inordinate impudence to defend the right of Americans, of all Americans, to travel freely to the Island, while saying nothing about the hundreds of thousands of Cubans who, thanks to the owners of our land, cannot return to Cuba.

There they are, those who have never blown up an airplane, or even introduced a flue virus. There they are, those who have never lifted a finger to assassinate, to threaten lives, who have never put their dirty money in Swiss bank accounts. And they cannot return to their homeland, because the same government that throws out tearful words in support of the poor, burdened Americans who would do anything in their power to visit Cuba if they weren’t prevented by the Evil Empire, this same government will not let its own people return.

Scattered to the ends of the earth, Cubans walk like zombies, numbed by nostalgia. They die, like Cabrera Infante and Jesús Díaz, tormented by a melancholy they can never conquer. They live, accommodating themselves to exile that some didn’t even choose, like the novelist Amir Valle, who they sent off to Berlin, raising the drawbridge behind him so he could never again enter the castle.

The same drawbridge that was lifted, also, behind the salsa bandleader Manolín, behind the TV personality Carlos Otero, after countless names, public and unknown, and that — hopefully I am wrong — they may also have lifted behind me.

And now, Cuba supports the legitimate right for Americans to step foot on the Island. There are moments when words fail me. And the impotence I feel on my lips is worse than the arsenic of Madame Bovary.

So every day I am less tolerant of the “friends of Cuba,” the dear foreigners with pink cheeks, to whom, months ago, I dedicated the post, The True Home of All. Those who spend their magical vacations on the sunny streets of Havana and never tire of saying, to Cubans, that we live in the best country in the world.

And so every day I can justify less those who, from a presumed intellectual fairness, approve with their speeches, or their silences, what happened today on a small island owned by a few, so few. This is not the time to shut up, dear intellectuals, dear think tanks of the middle world:

“There are times, in life, in which those who are silent become guilty, and to speak out is an obligation. A civil duty, a moral challenge, an unmistakable imperative from which one may not excuse himself.”

So said an Italian whose name, so sublime, so worthy, I intend to give to the daughter I want to have in the future. So said Oriana Fallaci when, after September 11, she could no longer sustain her silence.

And if, after eight years since the talented — and yet inconsistent — Eduardo Galeano wrote his cathartic text, Cuba still hurts; it’s because it excludes and censors, because it represses and silences. If Cuba still hurts because it violates the rights of us, its children, and yet defends the rights of foreigners to stand on our blessed soil, then may the docile be shamed alongside the guilty, the silent next to those responsible, and remember that History — contrary to what many think — rarely absolves anyone*.

Translator’s note: “History… rarely absolves anyone” is a reference to Fidel Castro’s famous closing statement at his trial for the 1953 attack on the Moncada Barracks, “History will absolve me.”

January 18 2011