JANUICEBERG

Orlando Luis Pardo Lazo

For the first time in months, I have sweated today. My forehead. It pearls itself first in innocent droplets. Then comes the sensation of steam on the temple. Smoke in the head. Sweat, sadness, salt. Filthy osmosis of bacteria and enzymes. Sadness that the Cuban climate remains real.

I need a faraway love. A love beyond the Artic Circle. Even when, these days, ice is melting there, too. Better yet. It will be a love of the end of times, so we can witness, together, the summer death of this planet. Criminal dog days heat. Mine will have to be a love who doesn’t speak a bit of Spanish. Or, in any case, one who speaks it so correctly that it comes out with a disguised accent; an affected sweetness, an academic dictionary, a post traumatic accent: lax, almost dyslalia. I ask for an immigrant language for my Nordic love, who will melt, immediately, under the horizontal rays of a murderous sun. I ask for an ephemeral love that leaves me, in the end, very lonely, with a tiny puddle of iceberg water under my feet. A love that makes me piss myself with sadness, but not with sweat. The urea is more drinkable than real tears.

If anyone knows of a love such as this, please pass along my personal information: it is everywhere in this blog and in half of the Cuban Internet (“Cuban Internet” is an exaggeration.) It will have to be a girl, for the time being. Sorry. A girl with Cuba in her head, on top of all contradictions, even if it is Cuba as a curse. A sweet girl with a bit of roughness to her, yet not foolishness. Scandinavian, but not scandalous. One who knows from the start what this pull-and-push love is all about. One who understands that we are already in the aftermath of not just my country. One who will want to dissolve herself in the high latitudes and never return again to the humiliation of our vertical light, disciplinary and totalitarian, official photons of a Tropical island in its sterile Revolution state of things.

A girl who is capable of breeding. Capable of gravity: to be in a grave state of me. With me in her interior body, in case she doesn’t die in her melting and I had to volatilize myself. Leap into the void, like that adult lady did last week, jumping from the top of the FOCSA building, in La Habanada. Hang myself from a nameless tree, like what that teenage girl, the daughter of diplomats, did to avoid, with prepubescent shame, a 2011 in this half-stupid island. To commit the arrogant act of disappearing, like the best José Martí once dreamed of before he almost outed himself from a shot and a mortal cutlass gash: “I know how to disappear.”

Today I have sweated and I realize I had forgotten that detail. I can not bear. I don’t wish to insist. I don’t have refuge in here for my guts. I don’t deserve such lack of winter illusion. As a child, “winter” and “life” were synonymous (it was my father’s fault; those stories he would plagiarize to make me sleep.) As an older guy, “winter” and “life” have become antipodes. I am leaving. I am defeated. Girl, come. Come convinced.

January 5 2011

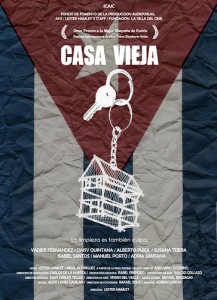

The fictional long-feature film Old House (Casa Vieja) has returned to the cinemas and to Screen #2 of La Infanta, where it can be enjoyed from 13-26 January by those who did not have the pleasure of watching it during the last Havana Film Festival, whose jury awarded it a Special Mention and the Popular Award, which lifted its maker’s Lester Hamlet’s ego; he expressed to Cacilia Crespo, journalist for The Film and Video Programme, that the re-writing of the play by Abelardo Estorino gave him the chance to speak from his essence and nationalism, to “narrate, from a human standpoint, a new conflict; to seek, to find, to suggest.”

The fictional long-feature film Old House (Casa Vieja) has returned to the cinemas and to Screen #2 of La Infanta, where it can be enjoyed from 13-26 January by those who did not have the pleasure of watching it during the last Havana Film Festival, whose jury awarded it a Special Mention and the Popular Award, which lifted its maker’s Lester Hamlet’s ego; he expressed to Cacilia Crespo, journalist for The Film and Video Programme, that the re-writing of the play by Abelardo Estorino gave him the chance to speak from his essence and nationalism, to “narrate, from a human standpoint, a new conflict; to seek, to find, to suggest.” The rest of the film revolves around reminiscences of the mother (Adria Santana) and her other children (played by Yadier Fernández and Daysi Quintana), the brother of the dying man (Manuel Porto), some exterior shots of the coastal town, and funerary and burial scenes where some government secretary directs the acts and is interrupted by the main character, who hates hypocrisy.

The rest of the film revolves around reminiscences of the mother (Adria Santana) and her other children (played by Yadier Fernández and Daysi Quintana), the brother of the dying man (Manuel Porto), some exterior shots of the coastal town, and funerary and burial scenes where some government secretary directs the acts and is interrupted by the main character, who hates hypocrisy. That’s where the “naked truths” and the “patriotic pride” end. There is nothing transcendental, neither in the acting performance of characters—limited by spaces and dialogs that were written for a different medium—nor in the geriatric atmosphere of stillness, poverty and lack of expectations. Perhaps the clue to the film needs to be looked for in the recreation of misery, the love frustrations of the marrying sister and in the untimely and honest street-sweeper played by Isabel Santos.

That’s where the “naked truths” and the “patriotic pride” end. There is nothing transcendental, neither in the acting performance of characters—limited by spaces and dialogs that were written for a different medium—nor in the geriatric atmosphere of stillness, poverty and lack of expectations. Perhaps the clue to the film needs to be looked for in the recreation of misery, the love frustrations of the marrying sister and in the untimely and honest street-sweeper played by Isabel Santos.