There are three, twelve-story buildings behind my house. Because they are lined up next to one another, people call the complex the Chinese Wall. Behind the buildings, there is a void full of dogs and rats, where improvised dumps frequently pile up heaps of garbage. In one of those dumps I made out three wooden suitcases, the sort of case that used to be taken to schools in the rural areas. The suitcases were slightly soiled but in good condition, with their hinges and lock mechanisms still in place. One was painted brown, and the others were unpainted and unvarnished. The raw plywood of one of the latter clearly read the name of the person who had owned it, and the name of her school.

The female students—these cases were for the use of girls only—would store in them, behind their padlocks, their Sunday clothes and food. I suffered from the syndrome of owning a case that proclaimed to be a “traveled” one, because it wore several stickers from faraway places like Gdansk and Praha. Made of reinforced cardboard and metal corner braces, my brother had taken it with him when he left for his studies in Socialist countries in 1962. The case had been the cause of much mockery, denouncing me as a “mama’s girl” in a sea of proletarians. In those times, when the future belonged entirely to Socialism, my suitcase denounced my socially privileged background. I enrolled myself in extra work hours with the system, and went vanguard so the suitcase would not get me into trouble due to my differentiated situation.

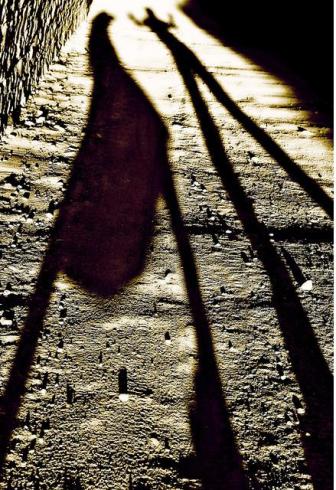

Seeing these three suitcases, all ready for their journey to oblivion, I thought about their owner, I thought about who I had been, and I thought of all those things that have gone to the garbage.

February 2 2011