It is Mayra’s first day on the street. The entire family is glad she is back. The atmosphere is very different from before, when she went to prison. Now her parents do not get upset when her eleven year old son tries to make them laugh with a stories about the comandante.

It is Mayra’s first day on the street. The entire family is glad she is back. The atmosphere is very different from before, when she went to prison. Now her parents do not get upset when her eleven year old son tries to make them laugh with a stories about the comandante.

Her mother, with her back turned, laughs at the boy’s joke. Myra is astonished. Before, her parents were constantly monitoring her speech. Under no circumstances would they have allowed her to say anything bad about the comandante or the Revolution. They would become incensed and explained why she should be eternally grateful: “Thanks to the revolution you have a house, an education, you don’t pay anything when you get sick.”

Sitting in the patio, breathing the fresh air, she thinks back again to her cell, the bricked-up windows, the humid air, and a stench of urine and excrement. She blinks. She feels a sense of relief. Yes, things have changed at home. Her parents now complain about “how bad things are.” One by one they count their “chavitos”—their small change in convertible pesos—to see if they have enough to buy a liter of cooking oil.

Mami is now 65 years old. She is fatter, spilling over the chair in front of the sewing machine. She works mending clothes for the neighbors. Papi is bony and ten centimeters shorter than five years ago. In two more days he will turn 70. He is retired from the Revolutionary Armed Forces and gets a “chequera,” a pension of 320 pesos, some thirteen dollars. He also works as a nightwatchman at a business near his house. He cleans patios and makes some extra money.

It is difficult for Mayra to imagine that once they went to the Plaza to joyously scream their support for the Revolution and Fidel Castro. They dreamt of a paradise where there would be no social inequalities and the exploitation of man by man would not exist. They believed in the Constitution, which compelled them to memorize the passage in the Preamble by José Martí: “I want to see that the first law of our Republic requires devotion by Cubans to the full dignity of man.”

But when the “special period” arrived in the 1990s, fanatics like her parents lost their enthusiasm. They began to tell her to talk in a low voice when she complained about those scheduledpower blackouts that lasted twelve hours a day, or when she occasionally even complained about the supreme leader. Now they become deaf and dumb when her son tells them that his dream is to become a ball player, to be able to travel, to live far away and to make a lot of money.

Dreams like that take her back to Doña Delicia, a women’s correctional facility. Images come to mind of when she went to work as a “jinetera”— a prostitute —on Fifth Avenue in Miramar. Images of police, acts of solicitation, a danger to society and five years in prison. It all happened so quickly. So stupid!

“I don’t have a ‘machango,’” she told the police. “If I had given them what they wanted, taken the easy route, I would not have gone to jail. But I would not let myself be blackmailed and so off I went. Who would have thought this would all get so complicated? It’s because of that son-of-a-bitch policeman, who tried to force me to kiss him. He was so disgusting. No, I am not sorry. If it happened again, I would do exactly the same. Ultimately, life is a game of Russian roulette.”

It seemed to Mayra that she was seeing the face of her father at the trial, the same one he had when her mother begged him to make piece with their other child, her brother, a “marielito,” one of the more than one hundred thousand people who left Cuba in 1980 through the port of Mariel. “We were dying of hunger,” she says, “but my father always had his pride. Even when Mami was sick with optical neuritis and almost died.”

“He now receives remittances from Miami, ’the nest of worms.’ How funny. When I went to prison, he was the president of the local Committee for the Defense of the Revolution. A few days later he resigned. He got a letter inviting him to visit his family ’in the bowels of the beast.’ At any rate he learned that it does not matter what path you take if you are following improbable dreams. I only want to get out of all this shit. That’s why I understand my parents, their silence, their sadness.”

After so many sacrifices, the harvest of ten million, voluntary labor, the workers’ guard, acts of repudiation, meetings, militant marches, slogans and informing on the private lives of others, it has not been easy for them to acknowledge that Cubans today are worse off than in 1959, when it all began. It is hard to accept that, after 53 years of “socialism,” the promise that we would have a perfect country has turned out to be a lie.

Mayra is still in the patio, her eyes closed. Her hair dances in the wind. She gently passes her hand over the sun that is tattooed on her neck. She sighs, looking around her. With a handkerchief she dries her tears. She gets up and goes back inside. She is the hostess. She must be with her family on her first day of freedom.

*Unpublished account by Iván García y Laritza Diversent, based on an actual case.

Photo: From a report on sex tourism in Cuba, published by La Prensa de Honduras.

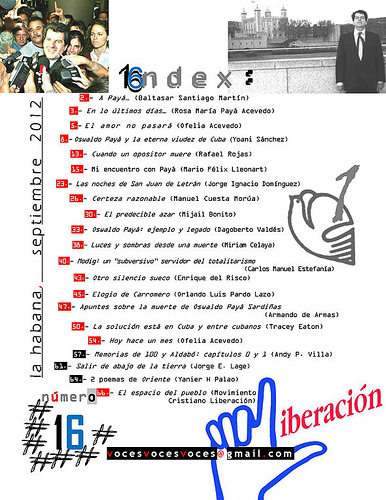

September 11 2012