![]() 14ymedio, Xavier Carbonell, Salamanca, 19 June 2022 — When I met Desiderio Navarro he was already an old man worn out by cancer. He used crutches and had little muscle left, little desire to speak. I did not know—he did—that the entire “universe” of Criterios*, the magazines, books, and translations, was about to disappear, to the relief of bureaucrats, private enemies, and public antagonists.

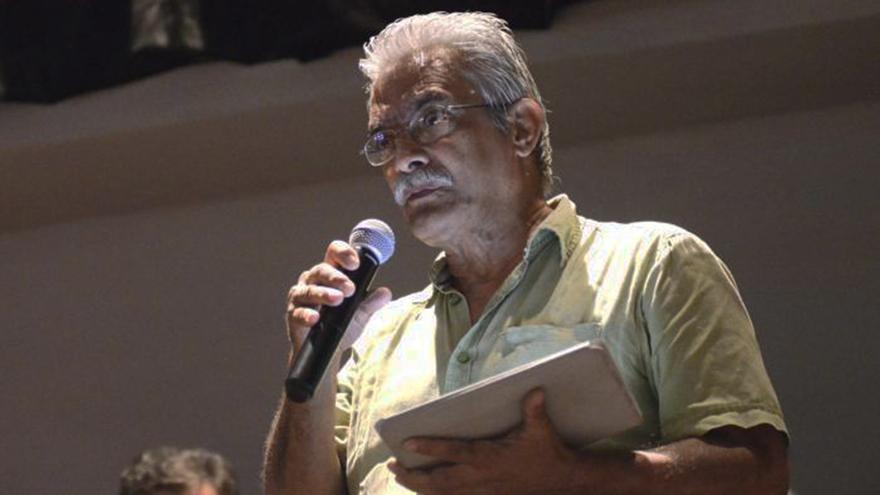

14ymedio, Xavier Carbonell, Salamanca, 19 June 2022 — When I met Desiderio Navarro he was already an old man worn out by cancer. He used crutches and had little muscle left, little desire to speak. I did not know—he did—that the entire “universe” of Criterios*, the magazines, books, and translations, was about to disappear, to the relief of bureaucrats, private enemies, and public antagonists.

Desiderio withered quickly. He left a solid and useful work, but he died alone, bitter, like the proverbial dog. Now he exists as a signature at the end of a prologue or in the credit of a translation, and we will gradually push him into oblivion, because the memory of the Cuban works at irregular intervals and does not distinguish between learning and trauma.

We also forget the hornet’s nest that, fifteen years ago, caused the television appearance of three former cultural commissioners in a context that could not have been more slippery: Fidel Castro’s illness after his collapse in Santa Clara, like a broken statue, and country’s the turn of the gears.

Demanding favors that reward some old loyalty is a characteristic of mafias. It was natural, therefore, to establish a link between the butchers of the Five-Year Grey Period, exhumed on television, and the rise to power of their longtime comrade, the man who put them on the board: Raúl Castro.

The appearance of those decorated mummies in 2007 could not be a good sign, and this was understood by the legion of intellectuals and artists who, precariously connected to their computers, began to send messages into cyberspace, asking for explanations and reading events between the lines.

That was called the “little email war,” although there was no such struggle — the “opponents” never responded — but rather a slow appeasement campaign. “It started in surprise and ended in a hangover,” Norge Espinosa said accurately. Desiderio Navarro, then a vigorous and stylish guy, officiated as marshal in what seemed to be the decisive moment for the Cuban intellectual so far this century. Time for criticism and frankness, defying in some cases the borders of the dying caudillo: the inside and the outside of the revolution.

There was no writer, musician, journalist or painter who remained silent. The debate, held for months in cyberspace, then took the form of “protected” meetings with culture officials, ministers and such. Bad thing. The first survival lesson for the intellectual is not to be locked in the same room with an official. It does not matter if it is a room or a theater, it will always lead to a torture chamber, a court or a cell.

Desiderio himself played a central role in the castration of that debate. He contributed to giving it a more peaceful, academic, politically correct character, when reality boiled beyond the lectures and halls. They were, if not the first, the already irreversible symptoms of national malaise and the state’s impatience to cut the matter short. The “little war” turned into an ambush; the ambush, into a firing squad; and then came silence.

A few weeks ago, on the primetime news broadcast, a mournful group of writers and artists placed flowers before the Great Stone, the Stone of Stones, the Stone-in-Chief. They made a profession of faith before the journalist who interrogated them, some cried, another remembered the el comandante and hugged the grave. I recognized several of the “pilgrims” and I confess that I never would have expected such a tearful display of affection. I wondered if they had always been so faithful, so unconditional, and then I remembered the old literary joke: no one seemed, but everyone was.

Where are the others? Those who have not been pacified by official anesthesia, those who did not sign the armistice after the “little war” and its aftermath. Most in exile; the others, crushed, imprisoned or jaded, battling the blackout to send the last email.

In his book on the events that concern us, Villa Marista en Plata, Antonio José Ponte made it clear that if the timorous and complicit intelligentsia that rules in Cuba is fighting for something, it is not because of privileges, trips and publications. They fight, even if it seems unreal, to gain time. “A time unconcerned with all accountability, free from checks… The borderless time within which the work is done. The time they will never find in capitalism.”

But doing business with Cuban power is always volatile and double-edged. There is no longer room for the innocence or passivity of Desiderio, to whom the government showed that it would not forgive even “soft” and organized dissent. Those to whom he offers a space are the usual mediocre, lame in talent, hallucinated, fanatical and snitches with guitar or microphone. Of course, they must be loyal like a Doberman.

Just take a look at the Higher Institute of Art or the Ministry of Culture, the University of Havana or Las Villas; to glorified puppets like Michel Torres, Israel Rojas or Humberto López, to gauge the agony of the new commissioners. They have air conditioning, they recite poems, they line up for gas at the Geely, they enjoy the Armed Forces’ beggar’s hotel, but they are hollow and would give their kingdom for a little trip where they can finally disappear into the crowd.

That is why, as long as they can live, they go to the Santa Ifigenia cemetery to pray so that that unnecessary “little war” will never be repeated, not even in fifteen years. They put flowers, they kneel and tremble, because that Gray Boulder will become – sooner rather than later – their wailing wall.

Translator’s note: *Navarro founded the journal Criterios in 1972.

____________

COLLABORATE WITH OUR WORK: The 14ymedio team is committed to practicing serious journalism that reflects Cuba’s reality in all its depth. Thank you for joining us on this long journey. We invite you to continue supporting us by becoming a member of 14ymedio now. Together we can continue transforming journalism in Cuba.