The American Gary Marks’s stay in Cuba, from 1998 to 2002, and his contacts with segments of our intelligentsia anchored in everyday survival, sparked the interest of the northern professional in documenting the contrasts. How? Through a DVD documentary about the unbreakable friendship of two artists, one who went rafting to Florida during the mass exodus of August 1994, while the other remained stranded in the island’s capital.

The American Gary Marks’s stay in Cuba, from 1998 to 2002, and his contacts with segments of our intelligentsia anchored in everyday survival, sparked the interest of the northern professional in documenting the contrasts. How? Through a DVD documentary about the unbreakable friendship of two artists, one who went rafting to Florida during the mass exodus of August 1994, while the other remained stranded in the island’s capital.

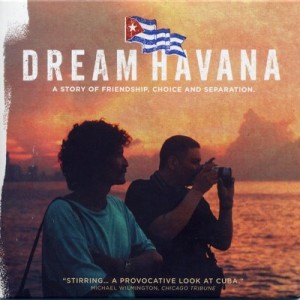

Friendship, this variant of love that exalts the human condition, has shone in all literary genres and artistic expressions such as music, theater and film, and the emotional memory of it is part of Dream Havana, which tells the parallel stories of the narrator, Ernesto Santana Zaldívar, and the poet, journalist and editor, Jorge Luis Mota, protagonists of chance, uncertainties and hopes in a kind of road movie that moves from Havana to Camaguey, Havana to the Guantanamo Naval Base, Miami, Chicago and Guadalajara, with poetry, the ocean, nostalgia, music and archival images as essential supports to the work.

Sponsored by Hexagram Productions, edited by Hannah David and Sharon Zurek, production by Erick Burton-Michale Taylor with help from Álvarez Martín; additional Photomontage from the BBC/A WVEC PTN, and a 58 minute version for television in 2009, which I enjoyed courtesy of Santana. You can find it at WWW.Dreamhavanamovie.com.

Dream Havana immerses viewers in layers of Cuban reality from the early eighties to 2000. It reports on society at the macro level through personal stories that reflect the certainties and failures of many lives suffocated by extreme circumstances. The film grows and suggests the traumas and frustrations of its protagonists. This debut by Gary Marks achieves artistic balance through the testimonial feeling of its voices, the agility of its shots, the photographic excellence of archival materials, the originality of the music composed by Descemer Bueno, and the poetic-existential discourse of Santana and Mota.

The symbolism of the sea as a bridge and backdrop of change, the authenticity of those participating in the scenes, and the play of the cameras and shots that emphasizes the brotherhood of the central characters, provide a counterpoint to the Cuban national drama without falling into extremes.

The mobility of the scenes reaffirms the shared role of Ernesto Santana and J.L. Mota. The first speaks and moves from poetry. The second from the urgency to leave and try his luck in a free environment. The balance is provided by friends and relatives of both, such as the wife and mother of Mota, and colleagues in common who interlace personal and social coordinates, re-created by the letters exchanged, photos and postcards and the allegorical lyrics of the songs.

Near the end, the profound Cuba of censorship, blackouts, speeches, hunger and distance, yields to the miracle of the reunion of friends, thanks to the Carpentier Prize awarded by the Cuban Book Institute to E. Santana’s novel Ave y Nada, presented at the International Book Fair of Guadalajara, Mexico, attended by J.L. Mota, distinguished by his time in the United States with the Hispanic Journalism Award.

The parallel scenes of the travel of each one, the respective airports, the walk of both along the Pacific Ocean and the hug and goodbye, seal the atmosphere of people in flight that characterizes the life and work of E. Santana and J.L. Mota, friends who meet again through Dream Havana, anchored in work and creation despite the waves and island twilight.

July 29 2011