![]() Among the shelves of the Frutas Selectas Food Stand in Holguín there are photographs of the revolutionaries Camilo Cienfuegos and Ernesto Che Guevara, as well as a large poster with the slogan of this State company: “Selected Fruits: the most select from the tropics.”

Among the shelves of the Frutas Selectas Food Stand in Holguín there are photographs of the revolutionaries Camilo Cienfuegos and Ernesto Che Guevara, as well as a large poster with the slogan of this State company: “Selected Fruits: the most select from the tropics.”

What is missing is fruit for sale.

Frutas Selectas is a food market that before the COVID-19 pandemic was a provider to hotels, restaurants and other tourist businesses. Now, in the absence of foreign visitors, its clients are the almost 300,000 inhabitants of this city in the eastern part of the Island.

Although the market was completely out of supplies, a line had started to form outside. Some waited sitting on a wall or leaning against the counter with their empty crates and their arms crossed.

“We are the only country in the world where we line up in underserved markets waiting for whatever arrives”

They hoped that at some point the store would put something up for sale, anything.

“We have been in line for two days to see if something arrives,” says Hilda Lobaina, a 72-year-old housewife whose mask does not hide the frustration in her gaze.

“We are the only country in the world where we line up in underserved markets waiting for whatever arrives” adds a retiree from the commerce sector who only wanted to identify himself as Antonio for fear of retaliation.

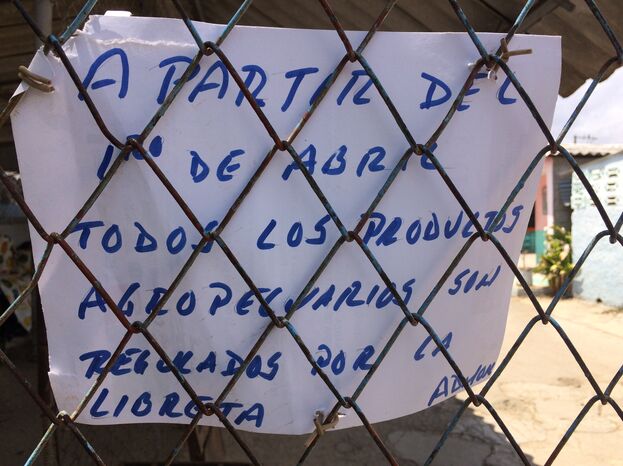

Since April 1st in Holguín’s number one State agricultural market, there is also a sign that reads that since April 1st all fruits, vegetables or viands “will be regulated by the [ration] book.” In other words, only a maximum amount of food per person is sold each month.

Until the arrival of the pandemic, fresh produce had not been subject to such strict regulations. In the case of plantains, the only product for sale that day, the limit was five pounds. Hundreds of people lined up to get them.

Raciel Céspedes, a 75-year-old man, explains that despite having arrived first thing in the morning and spending two hours in line, he still hasn’t gotten the “fongos,” as this type of dwarf plantain is known here.

“In my house there is no food and if I don’t buy something for lunch I won’t eat today,” says Céspedes.

In recent months, the scenes of undersupplied markets and long lines or of those with a single product for sale have been repeated throughout the country.

Cubans, who have suffered from food shortages for years, have seen the situation worsen as the state-controlled economy plunged into a deeper crisis since the arrival of COVID-19.

With its main sources of income declining and without access to international financial markets, the Cuban State has more difficulties than usual obtaining foreign exchange

After years of slow decline in the wake of the crisis in Venezuela and the tightening of US sanctions, the pace of economic collapse now appears to have accelerated. The main symptom of the problem is a severe food shortage.

Today’s Cuba does not produce enough food to supply its population and needs to get it overseas in dollars or euros.

With its main sources of income declining and without access to international financial markets, the Cuban State has more difficulties than usual obtaining foreign exchange.

Although precise and up-to-date economic statistics are not disseminated in the country, the information available abroad highlights the precariousness of the situation.

According to official data from the International Settlement Bank (BIS), at the end of June 2020, Cuban companies had the equivalent of 867 million US dollars on deposit in bank accounts abroad.

For Cuba, this is the worst figure since the end of 2005, according to the BIS records.

In the last 15 years, Cuba had an average of 2,200 million US dollars in foreign currency at the end of each quarter, according to the statistics of the aforementioned institution. Now it’s averaging less than half.

This is translating into a drastic reduction in imports, which fell by 34% in the first eight months of this year compared to the same period in 2019, according to data from the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

Each month until August, Cuba was importing about 210 million US dollars less than the previous year.

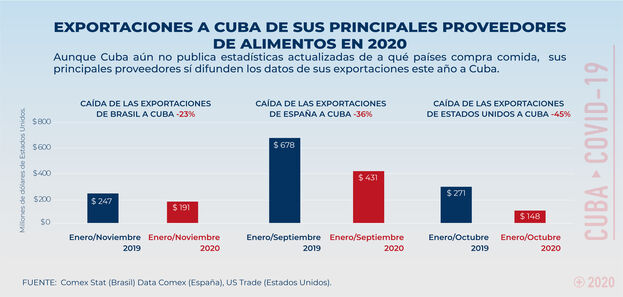

Among the countries that Cuba has stopped buying from are its main food suppliers, such as Brazil, the United States and Spain, according to official data from those countries.

Sales from Brazil to Cuba decreased 23% compared to last year; from Spain, 36%, and from the United States, 45%.

This translates into less chicken, oil, rice, corn or beans, and the fear is that a situation like the one experienced in the 1990’s, during the so-called Special Period, will repeat itself.

In a country that prided itself on having eradicated hunger, the government has had to resort to donations from the World Food Program (WFP) to ensure the availability of beans, rice and oil in five eastern provinces

Today, virtually all daily consumer products are subject to some form of rationing. In a country that prided itself on having eradicated hunger, the government has had to resort to donations from the World Food Program (WFP) to ensure availability of beans, rice and oil in five eastern provinces, as the organization explained in a recent report.

“Without a doubt, this is the most critical situation that has affected Cuba since the Special Period,” asserts for this report Economist and former professor at Baltimore’s John Hopkins University, Ernesto Hernández-Catá.

Other prominent Cuban economists have agreed on this diagnosis. “Cuba is suffering the worst economic crisis since the one that occurred in the 1990’s, after the collapse of the USSR,” Carmelo Mesa-Lago, an academic at the University of Pittsburgh, recently wrote.

In most countries, the prevailing perception is that the current economic crisis has a culprit: the pandemic. In Cuba, many economists present a more complex analysis.

“Cuba has arrived at a crisis in crisis” Havana University professor Omar Everleny Pérez has maintained in several interviews. In his opinion, Cuba was already going through a period of shortages in 2019 due to the country’s economic difficulties in exporting products or services, generating foreign exchange and importing food from the proceeds.

Other experts agree that, although the current crisis has conjunctural causes, the most important ones are the structural ones, related to the Cuban economic model.

The Economist even declared, in a discussion organized by the magazines El Toque and Periodismo de Barrio, that “the existing shortages in the stores where the population obtains its foods has nothing to do with the pandemic”.

Other experts agree that, although the current crisis has conjunctural causes, the most important ones are the structural ones, related to the Cuban economic model.

“Cuba suffers from a chronic currency crisis due to the insufficiency and decline of exports of goods over many years (…). Although the crisis has conjunctural elements stemming from the pandemic, the serious problems are structural”, explains economist Luis R. Luis, one of the directors of the Association for the Study of the Cuban Economy (ASCE) for this report.

“The current crisis has two elements. One reflects the effects of the pandemic. The other is the character of the Cuban economy, which is rigid, distorted and inefficient. This will not be resolved with the end of the pandemic and will require fundamental reforms of the economy”, details Professor Hernández-Catá.

Among many experts there is the feeling that Cuba has reached the end of a road and what is coming is a transition period in which the country will have to find a new model.

If the population’s standard of living did not fall further, it was mainly due to the sale of medical services, tourism, remittances from Cubans living abroad and trade with Venezuela.

In the last two decades, Cuba practically ceased to be a sugar producing country, but it failed to develop another industry of similar magnitude that would allow it to generate foreign exchange.

If the population’s standard of living did not fall further, it was mainly due to the sale of medical services, tourism, remittances from Cubans living abroad and trade with Venezuela. The latter has been, by far, the main economic activity in the country in recent years.

Cuba now faces the uncertainty of whether visitors will return en masse and whether emigres will continue to send as many remittances. But it also faces the certainty that its most lucrative activity, its relationship with Venezuela, will no longer be as beneficial as before.

This has motivated some experts to consider that the country cannot continue to think about depending on a single activity or partner.

“For the past 60 years, Cuba has been unable to finance its imports (…) without the substantial aid or subsidies from a foreign nation. That is the long-term legacy of the Cuban socialist economy,” wrote Professor Mesa-Lago in an article published last year.

“History has shown that dependence on Soviet subsidies first, and later on, swaps (exchanges) of Venezuelan oil for doctors were a serious mistake. These political agreements are unhealthy because they do not depend on the comparative advantages of their participants, but rather on the largesse of basically fragile countries like the USSR and Venezuela”, concludes Professor Hernández-Catá.

When Venezuela’s economy began to collapse around 2015, the impact on Cuba was not immediately felt. An initial slow decline of the country’s economy began then, and ended up worsening with the arrival of the pandemic.

Since the beginning of the century, Cuba has sent tens of thousands of workers, mainly health workers, to Venezuela. In exchange, in addition to cash, Cuba received oil that was refined and re-exported to Venezuela itself and elsewhere.

When Venezuela’s economy began to collapse around 2015, the impact on Cuba was not immediately felt. An initial slow decline of the country’s economy began then, and ended up worsening with the arrival of the pandemic.

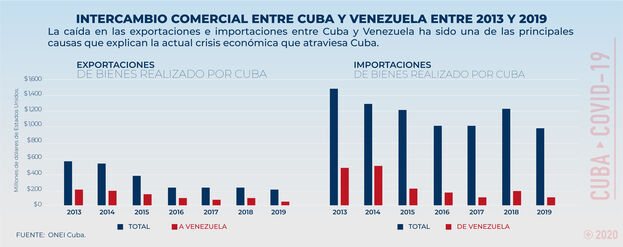

All this trade came to represent 20% of Cuba’s gross domestic product (GDP).

Although the country has only published information on the benefits of its relationship with Venezuela on specific occasions, the calculations made by some economists highlight that trade with the “sister” Bolivarian Republic was the Cuban State’s biggest business.

Trade with Venezuela also allowed the State to keep pace with imports of basic products that the population needed and that are now in short supply.

According to the calculations of academic Luis R. Luis, the relationship between the two countries reached its peak around 2014. At that time, the export of doctors and other professional services reached about 7.5 billion US dollars. Venezuela paid slightly less than half, 3.4 billion, in barrels of crude oil and another 4.1 billion in cash.

But as Venezuela entered the worst crisis in its history and, as sanctions by the United States and other countries tightened against it, this trade was reduced.

Cuba, which has an abundance of health professionals, only partially reduced the size of its missions, but Venezuela found it increasingly difficult to pay for them in crude oil or dollars.

Luis estimates that the oil payment went from $ 3.4 billion in 2014 to just under $ 900 million last year, a drop of 74%.

These data are consistent with official figures released by Cuba’s National Office of Statistics and Information (ONEI), which show how the value of trade in goods with Venezuela, which consisted mainly of crude and refined oil, plummeted between 2013 and 2019. The value of exports to the South American country fell almost 90%, while that of imports fell 63%.

With less oil to refine and sell in dollars, the country began to suffer from shortages.

“The economy has been hit by declining imports of Venezuelan oil,” noted a November 2016 report from the Embassy of the Netherlands in Havana. “As a result, foreign exchange earnings from oil re-exports fell and led to a cash shortage that is threatening Cuba’s ability to meet its payments with foreign suppliers.”

According to the ONEI, the Cuban State’s debts with foreign suppliers doubled between 2013 and 2017.

But the problem went further. As we received less and less payment in kind, the amount that had to be disbursed in cash grew. What happens to this money is an enigma, given that Cuba hardly publishes information about its economic relationship with Venezuela.

In 2019, the ONEI reported that Cuba had exported medical services valued at almost 5.4 billion dollars. It was the second time that the authorities published this data

Until now, it is not known if the cash is being paid, or in what currency the payment would be made (in US dollars or Venezuelan Bolivars, for example) or how much the debt currently amounts to.

In 2019, the ONEI reported that Cuba had exported medical services valued at almost 5.4 billion dollars. It was the second time that the authorities published this data.

But it is not clear if that sum, which in large part comes from Venezuela and represents the largest income for the country, really reached bank accounts of the Cuban State or if the money only exists, “in theory”, for the purposes of State accounting. There are reasons to doubt.

The country governed by Nicolás Maduro has suffered in the last five years the greatest economic collapse that has been registered in a country at peace in decades, and its capacity exporting oil and getting dollars in return has been declining for years.

This means that Venezuela is finding it increasingly difficult to pay off its debts to Cuba. Several Cuban economists take it for granted that the country has not received what it’s owed from Venezuela for years.

In a 2018 analysis for the Cuba Study Group, economist Pavel Vidal stated that the ONEI had not adequately accounted for the country’s economic activity, since it had reflected money as income that in reality there was no way to collect from Venezuela in the short term.

“They are assuming that Venezuela’s inability to pay for medical services is due to a temporary liquidity problem. In reality, it is a structural problem.”

“They are assuming that Venezuela’s inability to pay for medical services is due to a temporary liquidity problem. In reality, it is a structural problem,” wrote Vidal.

ASCE academic Luis R. Luis also stated in a recent article that Venezuela lacks the ability to pay Cuba in hard currency and that it could only do so with crude oil or in the national currency, the bolivar.

This constitutes a serious problem for Cuba, since Venezuela produces less and less oil, and its tankers – and specifically those traveling to Cuba – have been subject to United States sanctions since the middle of last year.

In addition, the bolivar has suffered constant devaluations that have practically turned it into a symbolic currency. Since Venezuela does not produce most of the food that Cuba needs to buy, its currency is also not good for purchasing it.

In an interview for this report, Luis assures that there are several facts that explain the current shortage situation in the country, such as the disappearance of tourism due to the pandemic, or the tightening of US sanctions, but not one has as much weight as Venezuela’s inability to pay.

“There has been a massive drop in these payments from a level of $ 6.6 billion in 2016 to less than $ 1 billion in 2019. Other crisis factors are much less important.”

“There has been a massive drop in these payments from a level of 6.6 billion dollars in 2016 to less than 1 billion dollars in 2019. Other crisis factors are much less important,” said the Economist.

So far, Cuban leaders have not publicly shown signs of the deterioration of the economic relationship with the Maduro government. But since Venezuela began to collapse, they have taken steps to seek alternatives to dependency, such as encouraging foreign investment.

At the end of 2015, they reached an agreement with the Paris Club, which groups together a series of countries, mostly European, to which Cuba owed billions of dollars. According to the deal that was reached, Cuba would open itself to investment from these countries in exchange for partial debt forgiveness.

“The deterioration Venezuela has experienced has led Cuban authorities to a repositioning process with a view to reducing the traumas associated with the possible collapse of relations with the South American country”, was the interpretation of the Paris Club when announcing the agreement.

But Cuba failed to attract significant foreign investment outside of tourism; dependence on Venezuela continued, the situation in the South American country worsened, and the United States sanctions against both governments tightened, making crude shipments even more difficult.

In the last year and a half, Cuban leaders began to prepare the population for difficult times, even mentioning the possibility of a new Special Period, which has a profound impact for Cubans, who remember that time as traumatic.

“The harshness of the moment requires us to establish clear and well-defined priorities, so as not to return to the difficult moments of the Special Period,” said President Miguel Díaz-Canel in an April 2019 speech.

A few days earlier, the first secretary of the Communist Party, Raúl Castro, made similar statements, alerting Cubans that, although the country now had a more diversified economy than when the Soviet bloc fell, they should prepare “always for the worst variant”.

As 2019 progressed, the “worst variant” took place. The statistics compiled by the BIS on deposits and loans in international banks indicate that the country has been running out of dollars and euros.

In March 2019, Cuban state-owned companies had the equivalent of 2.3 billion dollars in foreign currency abroad. By December, the figure dropped to 1.3 billion and continued to fall in 2020

In March 2019, Cuban state-owned companies had the equivalent of 2.3 billion dollars in foreign currency abroad. By December the figure dropped to 1.3 billion and continued to fall in 2020. By the end of June, already in the midst of the pandemic, 867 million were available, the worst since 2005.

Although Cuba has close ties with countries such as Russia or China, it hardly imports food from them. To buy food (except rice, which is bought from Vietnam, mainly), the country needs dollars or euros with which to pay Brazilian, American or Argentine suppliers.

The country was running out of foreign exchange and, consequently, without food.

Long lines, irregular distribution and months-long disappearance of some products have been a cyclical problem in Cuba for decades.

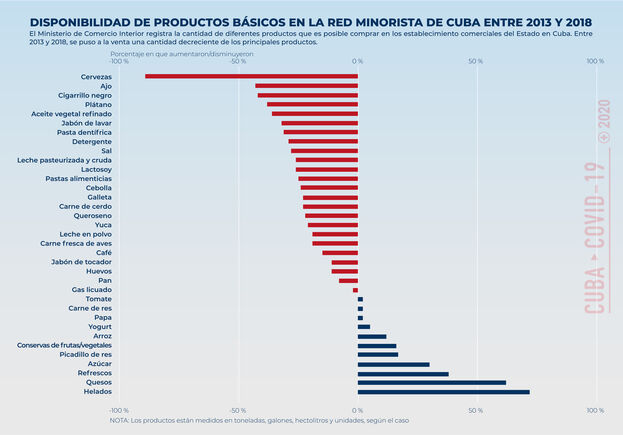

However, in recent years, at the same time that the Venezuelan economy has collapsed, there has been a slow decline in the stocks of everyday consumer products.

Out of a selection of 64 commonly used products, 39 experienced a drop in their availability in stores between 2015 and 2018, according to data from the ONEI. The amount of cooking oil for sale in retail stores decreased by 36%; soap and toothpaste, 30%; fresh milk, pasta and pork, 25% and powdered milk and chicken, 20%.

Although the ONEI has not yet released data for 2019, many Cubans agree that the availability of products continued to fall and that the shortage worsened even more during the pandemic.

Official data available abroad show that the country is importing considerably less food than a year ago.

Purchases of frozen chicken from the United States last August were 25% of the same month’s imports in 2019. Purchases of Brazilian soybeans between January and September of this year (used to make cooking oil) were half of those during the same period last year.

Another phenomenon must be added to this: last year’s decline of the national agricultural production. According to an analysis by economist Pedro Monreal, between 2018 and 2019 (last years with available information), 12 products groups for everyday consumption experienced a decline. The amount of beef produced declined by 23%, and rice by 18%.

In a recent official report, the authorities recognized that in 2020 some 30,000 tons of rice will not be harvested due to lack of fuel

Although data are not available for this year, it is possible that this downward trend has continued, since the shortage of foreign exchange has also negatively affected imports of fertilizers and fuels necessary to maintain production.

In a recent official report, authorities recognized that some 30,000 tons of rice will not be harvested due to lack of fuel in 2020. This is the equivalent of about 10% of the national production.

The shortage is significant in all the cities of the country and has resulted in long queues from the early morning hours in State stores and the rise of a digital black market in which products fetch irrational prices.

“The main problem we have is food. It cannot be that in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic people have to go out and spend all day trying to buy chicken. It is something elementary,” said Economist Omar Everleny Pérez in the aforementioned meeting with independent magazines.

There are long lines In Holguín every day in front of stores or markets, especially if there has been a rumor that some establishment will put a high demand product for sale which has been absent for weeks.

During an August morning, María Eugenia Durán, a 67-year-old woman, had been waiting for two hours to buy cassava in a market in the city. It was the only product for sale in the establishment.

Visibly tired and with her bag empty, Durán complained that “everything is scarce and to buy very little you have to stand in endless lines. Sometimes you can’t buy anything because the products run out, there are shortages of all basic products and food since last year”.

Economist Luis assures that as long as foreign exchange is scarce, the country will continue in a food crisis. “Recent data suggest that the worst case, a nutrition catastrophe, will be avoided at a high cost by cutting imports such as medicines, fuels and other raw materials”, he states.

For Cuba, insisting on the exportation of its health services during the pandemic has resulted in a tremendous blow to its international image as a medical power.

________________________

Editor’s note: This work was supported and edited by the Institute for War & Peace Reporting (IWPR), an independent non-profit organization that works with media and civil society to promote positive change in areas of conflict, closed societies and countries in transition throughout the world.

____________

COLLABORATE WITH OUR WORK: The 14ymedio team is committed to practicing serious journalism that reflects Cuba’s reality in all its depth. Thank you for joining us on this long journey. We invite you to continue supporting us by becoming a member of 14ymedio now. Together we can continue transforming journalism in Cuba.