![]() 14ymedio, Juan Matos, Manzanillo (Granma Province), 2 February 2024 — In the San Francisco cemetery complex, fifteen minutes by car from the municipal necropolis of Manzanillo (Granma), up to 200 dead were buried in a single day in mass graves during the worst time of the pandemic. Mobilized by order of the authorities, the gravediggers were unable to cope and had a clear instruction: three hours after death they had to remove the body.

14ymedio, Juan Matos, Manzanillo (Granma Province), 2 February 2024 — In the San Francisco cemetery complex, fifteen minutes by car from the municipal necropolis of Manzanillo (Granma), up to 200 dead were buried in a single day in mass graves during the worst time of the pandemic. Mobilized by order of the authorities, the gravediggers were unable to cope and had a clear instruction: three hours after death they had to remove the body.

The mounds, the large expanse of removed land and the precarious wooden crosses in the cemetery of San Francisco still attest to what happened in those days. “The cemetery was very small and they had to expand it. They had to prepare the area for the pandemic deaths,” one of the local employees explains to 14ymedio. “All the people buried there were from Manzanillo.”

“It was the hardest moment of my life,” says a former Manzanillo gravedigger, who remembers “as if it were yesterday” piling up the corpses. The situation was extreme. “In Manzanillo there was not, nor is there now, space for so many deaths,” he explains; hence, the leaders transferred several gravediggers to the rural community of San Francisco to take care of the mass burials. “I had been at work for many years and I hadn’t seen anything like it. A lot of people died.”

Carmen, a health worker who lost her mother a few days after she gave her “a bad cold” remembers how sudden the process was. “In the hospital they gave her the rapid test and then the PCR, and she tested positive. They took her up to a room, and I couldn’t accompany her. They would only give me information about her on the phone. I was desperate.”

The phone stopped ringing for several days, and Carmen, taking advantage of her contacts, moved heaven and earth to know what was happening with her mother. “I found out that she had been dead for three days and was buried in San Francisco. I wanted to die; they had deceived us, making us believe that she was alive. I never knew the exact place she was buried, and I was so traumatized that I prefer to remember my mother alive. I’ve never been to San Francisco to see her again.”

“I never knew the exact place where she was buried, and I was so traumatized that I prefer to remember my mother alive. I have never been to San Francisco to see her again”

Returning to “normality” since the pandemic was not easy, the former gravedigger says. The cemetery of Manzanillo – his former place of work – where several heroes and mambises of the stature of Bartolomé Masó and Francisco de Céspedes are buried, is in deplorable condition.

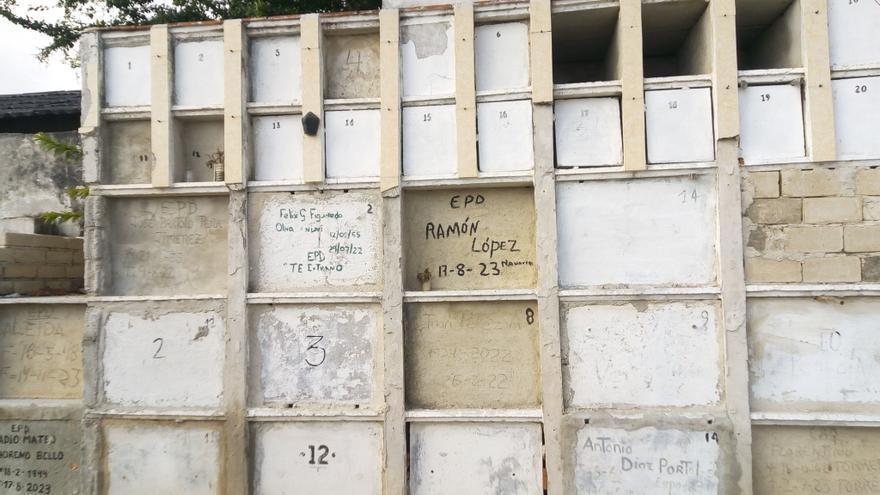

“There are more than 1,000 tombs here,” calculates the former employee, many of them with historic value and artistically worked. The general tone of the cemetery, however, is not of the old Republican tombs, with marble statues, angels and crosses, but of the cement niches between the weeds and the burned grass.

The former gravedigger regrets that the staff of the cemetery cannot do more, but with “a little more than 2,000 pesos” – the salary paid by the administration – the payroll is now reduced to two workers, of the 12 who, ideally, would be taking care of a historic cemetery like that of Manzanillo.

Drawn by hand and with paint of any color, the epitaphs of the “dead of the Revolution” are written on sickly tombstones, which barely support the structure of the niche. The words “I miss you”, an asterisk to mark the birth and a cross to indicate death, scraped on the cement, are the only remaining testimony of those who fought for Castro.

“Here are our loved ones. It’s disrespectful,” complains a woman who was visiting and cleaning her family crypt, besieged by grass and enveloped in a plague of smoke. Next to the pantheon are two destroyed coffins on the grass – with rags inside – that have been set on fire. “We have to set fire to the grass because we can’t weed it. There’s too much,” explains the employee.

“There are self-employed in Manzanillo who can be hired for 500 pesos a month to clean the graves,” explains the former gravedigger. “But it is generally the relatives who have to take care of them. The gravediggers don’t have time for anything. The Pantheon of the Fighters, for example, is completely unattended, and that is not their fault. The area should be treated better.”

The situation of the Manzanillo necropolis has reached the official press, which last week urged the authorities to take care of it. Juventud Rebelde claimed it is a place of absolute “patriotic richness, with art deco, inscriptions and an eclectic style; tombs with marble, bronze, iron, cement and glazed tiles,” and an important “decorative style” with numerous sculptures made in Spain, Italy, France and the United States. At the end of the list, the newspaper called on the leaders to raise the miserable salary of the employees.

The former gravedigger knows the place well. In his opinion, the workers have done too much on their own. The niches were built to alleviate the lack of space, where there are often “more than 100 people buried.” The crypts, built with the worst quality materials, tend to break.

“There was a case of disastrous collapses, and we found ourselves in the painful situation of having to collect the human remains,” remembers the former gravedigger. “We did it with a lot of respect, but sometimes we didn’t even know who was who, and we had to put them in other graves.”

Translated by Regina Anavy

____________

COLLABORATE WITH OUR WORK: The 14ymedio team is committed to practicing serious journalism that reflects Cuba’s reality in all its depth. Thank you for joining us on this long journey. We invite you to continue supporting us by becoming a member of 14ymedio now. Together we can continue transforming journalism in Cuba.