![]() 14ymedio, Juan Matos, Manzanillo (Granma province), April 11, 2024 — With orders from the municipal company Aqueduct, a backhoe opened a long ditch in the central Martí Street, in the port city of Manzanillo. The objective: to install a new central pipe to replace the old one, which had multiple leaks. But the cure, say the neighbors, given the ditch and debris that make the street impassable – is worse than the disease. In its path, the vehicle not only tore off the pavement and the remains of the old pipe but also broke the secondary connections that take water to the houses. Asked by 14ymedio, the workers brush it off: “Those connections aren’t a priority; we’ll see what to do with them later.”

14ymedio, Juan Matos, Manzanillo (Granma province), April 11, 2024 — With orders from the municipal company Aqueduct, a backhoe opened a long ditch in the central Martí Street, in the port city of Manzanillo. The objective: to install a new central pipe to replace the old one, which had multiple leaks. But the cure, say the neighbors, given the ditch and debris that make the street impassable – is worse than the disease. In its path, the vehicle not only tore off the pavement and the remains of the old pipe but also broke the secondary connections that take water to the houses. Asked by 14ymedio, the workers brush it off: “Those connections aren’t a priority; we’ll see what to do with them later.”

According to the workers, “a lot of water is lost in the main pipes,” which is why the State managers have made their replacement an objective. “We have positioned ourselves to eliminate the leaks so as not to lose water in the pumping process,” they explain.

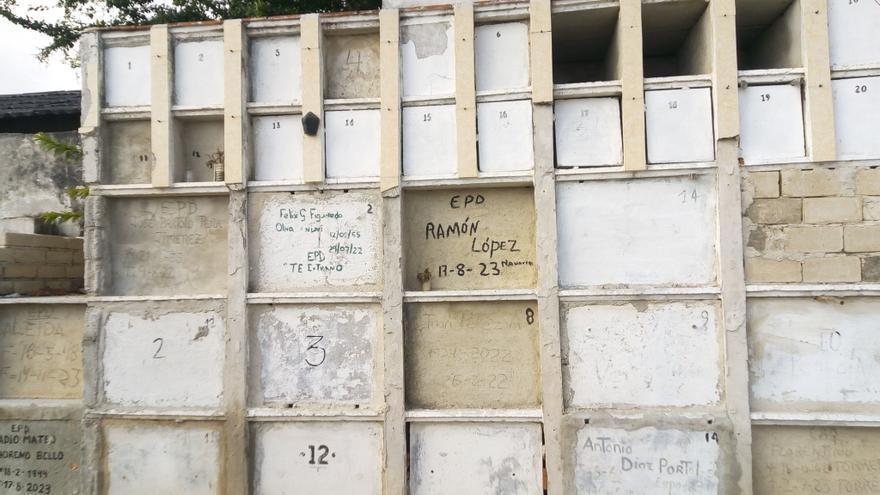

Commenting on the shortage, the government’s Round Table TV program said this Wednesday that the water cycle – the frequency with which it is pumped into homes – is 10 days. The reality, however, is that the water is arriving once a month. The interval is painful and forces families to carry the water or, if the pocket book allows, to buy it. The replacement of the connection on Martí and other streets in the city center complicates the situation and has caused multiple complaints in the neighborhood.

“They finished with the pipes of all the houses,” says Orlando, 47, while pointing to small tunnels on both sides of the ditch. The connections for each household passed through there, and in many of them you can still see fragments of the pipe. “I don’t know what problem they solved. The main continue reading

Nearby, at a neighbor’s house with a well, a group of boys gathers around the pump to fill gallon-jars and bottles, which they then transport back to their homes in construction trucks.

“They haven’t told us when they are going to redo what they have destroyed. As prices are today, it is impossible for us to fix this with our own means,” he says. Others look at the plastic structure with suspicion and predict little future. “There are still leaks there,” they insist, among the mountains of excavated earth that have already been blocking traffic on Martí for several days.

The water situation, fueled by the terrible state of the pipes and the inefficiency of the Government, goes from one end of the Island to the other. The crisis does not reveal any leader, to whom – desperate for the lack of supply – the neighbors can come in the first place. In Santa Fe, one of the poorest neighborhoods of Guanabacoa, in Havana, officials do not agree on the reasons for the shortage. From the drought of the reservoirs to the pollution of the water, they spare no excuse for those who demand an explanation. In the mouths of leaders in whom no one believes, multiple causes are attributed to the same phenomenon. In the hard way, families have learned that the leaders only react when the same vessels they use to conserve water resonate during a cacerolazo*.

The hope of many is the water trucks, which the State sends sporadically and without the necessary equipment to pump to the tanks that families usually install on the second floors. The elderly of the neighborhood go to the tanker truck, without hoses, and carry what they can as they can, because they don’t want to resign themselves – neighbors told this newspaper – to “drinking from the puddles.”

In the case of Santa Fe, water comes more frequently, but the service is unstable. It’s “abusive,” the neighbors explain, that the State sends only one pipe for a whole block. From Santa Fe, on the outskirts of Havana, to the eastern municipality of Manzanillo, the feeling is unanimous: “Their pipe is worn out”

*Translator’s note: A common form of protest in Latin America where people beat on pots and pans

Translated by Regina Anavy

____________

COLLABORATE WITH OUR WORK: The 14ymedio team is committed to practicing serious journalism that reflects Cuba’s reality in all its depth. Thank you for joining us on this long journey. We invite you to continue supporting us by becoming a member of 14ymedio now. Together we can continue transforming journalism in Cuba.