They opened the window when the door was closed, but the challenge is to cross the threshold of freedom without subterfuges or ideological concessions.

The first generation I want to talk about is that of my father. A train driver, a Communist Party militant, a member of the political process that came to power in Cuba in January of 1959. He could not choose, he just followed the course designed by others who barricaded themselves behind the name of the historic generation and came down from the mountains, bearded, young, possessors of hope, in a convulsive and memorable era. continue reading

My father was a child at the time and saw how the country around him skipped a beat. The streets were euphoric, anthems filled every space and in the photos from that time his contemporaries are smiling and optimistic in front of the platform where the Maximum Leader speaks for hours, with his index finger defiantly extended. To my father’s generation fell the heroic tasks, like the literacy campaign, the voluntary labor to catapult the country to the highest standards of prosperity and knowledge.

However, what most marked that time was the sensation that they were working for the future, that all this sacrifice and energy would end up building, for their children, a better tomorrow. They were young, they wanted to have fun and be together, but they accepted being led and reduced to the attitude of mere soldiers, so that those who came later would inhabit a more prosperous and more free Cuba.

In order to achieve that dream, that generation set aside in great measure the rebelliousness that belongs to that age, accepted a foreign doctrine as distant as Marxist-Leninism, and offered their best years on the altar of history. No contribution was enough, so the government asked for more sacrifice, less individualism and above all, no complaining.

Their names were the first signed up for the so-called libreta, the ration book for food and manufactured products that were distributed to Cubans in identical amounts, to avoid social differences and the appearance of that demonized middle class that Fidel Castro’s regime had erased through confiscations, stigmatization and exile.

My father could only choose atheism in a Cuba where families hid their prints of the Sacred Heart of Jesus at the back of the room and avoided even saying “thank God,” and postponed for several decades the celebration of Christmas. For the prevailing ideology, religion wasn’t just the opiate of the people, but endowed the individual with a spiritual world to which the Party had no access. When Cubans escaped in a prayer, in a supplication, the bureaucrats and materialistic theorists lost ascendancy over them.

In every form you had to fill out to go to school or start a new job there was the question about your religious beliefs. Many hid their crucifixes under their shirts, emphasized that there were “trusted comrades” and marked “no”… saying they believed in nothing other than the Revolution, its leader and the Party. In this and other ways the basis of the double standard that runs through Cuban society today was set.

These were the Cubans who, on becoming young adults a decade after January 1959, filled the ranks of the soldiers who left for internationalist wars in far off Africa. They didn’t know it, but they were just canon fodder, “toy soldiers” that the Soviet Union deployed at will in the turbulent war scenario of the Cold War. Thousands went mad, died, and wept in those latitudes, without a good understanding of how the people on our island got involved in such a conflict.

But those who were also young back then had to say “goodbye” to many of their relatives once more, when they were forced to emigrate from Camarioca or through the Port of Mariel. Many of them, beardless and confused, were used as shock troops to scream, at their own family members, that official slogan with which Cubans confronted Cubans, “Out with the scum!”

Uniformed, with military haircuts and optimistic about the future, these young people began to have their own children, whom they nursed on the belief that they would live in Utopia, with absolute equality and happiness for everyone. It was my generation that would arrive in a world where everything was decided and programmed.

I was born in the midst of the absolute Sovietization of Cuban reality. The Three Kings of our Christmas celebration, olive oil and privacy were all simply memories from a past that should not return. We were the New Man that knew nothing of capitalism, the exploitation of man by man, the market, the law of supply and demand, respect for privacy and, of course, we also knew nothing of freedom…

We all knew, in that Cuba of the seventies and eighties, how our classmates dressed or what they ate, because it was exactly the same, a carbon copy, of what we ourselves ate and wore. Using the first person singular, “I,” became a problem, so we talked about “us,” we were comrades and projected collective dreams and the longings of the platoon.

With the concept of the “masses” that need to be be managed from above, my generation was sent to schools in the countryside. A social and teaching laboratory where we would be Cubans more committed to the cause, people disinterested in all material things, and ready, at any moment to exchange our schoolbooks for a gun, if the fatherland – or at least those who called themselves the fatherland – needed us.

However, the human being in an environment of excess indoctrination always reserves a piece of themselves, where the cacophony of power is not heard and where no ideology has access. That redoubt, defended with masks of complacency and hidden from colleagues, relatives or the neighbors who might denounce you, was the refuge of our generation.

They, the powers-that-be, promised us Utopia, but we wanted to enjoy the present. So we pretended to obey while we incubated rebellion. We yelled the slogans like automatons and minutes later we’d already forgotten the words we shouted. We learned to lie, to put on a mask, to unwillingly applaud, and to promise eternal fidelity when inside there was only apathy and doubt. In short, we learned to survive.

We came to puberty and the Berlin Wall fell. We weren’t the ones wielding the chisels and hammers that brought down the symbol of an era, but every blow against the stones echoed in our heads. My father cried for that communist East Germany that he knew from a trip he’d earned as a vanguard worker, designed so he would know the future. But my generation felt a tingling, a satisfaction…our Sugar Curtain could also fall.

With the Communist Party Congress in 1991, in which it was accepted that religious believers would be allowed in the only political organization permitted in the country, we saw how our parents pulled out their old hidden religious objects.

The hunger also came, that burning stomach that doesn’t let you think about anything else. With the implosion of the Soviet Union and the “socialist camp,” Cuba lost the subsidies and the “fair trade among peoples” that had kept the country afloat for decades. That currency that had bought our fidelity, that gravitational field that we orbited around the Kremlin, vanished.

We came up against our own reality. It was hard, sad, without expectations. Nothing resembled those projections of the future with which my father put me to sleep when I was a little girl. His generation had inherited a moribund doctrine and to us fell the heavy task of burying it.

The Rafter Crisis that erupted in August of 1994 was one of the many ways that my contemporaries found to bury that mirage. We didn’t confront power in a public plaza, nor tear down the walls of control surrounding us. A good part of Cubans preferred the sea, the waves and rickety boats as the path to escape.

On Havana’s Malecon we watched them assemble the rafts of disillusionment, people my father’s age and the new shoots, energetic and young but frustrated. They left, we said goodbye and the cynicism began, the nothingness, the stage of not believing, of no illusions but also no rebellion. We arrived at this moment in our national history that could be called “every man for himself.”

Between the sound made by the oars of the rafts that sailed the Florida Straits and the stubbornness of the power that kept calling us to resist the economic vicissitudes, my generation began the difficult task of being parents. Those we brought into the world were the babies of disenchantment: the grandchildren of those who cursed having given their best years to a failed project and the children of a generation that should have been the “New Man” but didn’t even manage to be a “good man.”

Not much can be asked of them, but the young people of today have been better than us. The generation of my son, who is 21 now, suckled our disbelief, heard us blaspheme in front of national television, buy in the black market, surreptitiously escape from the public marches and hope – in a whisper – that the future wouldn’t be the one our parents dreamed of. Because we already understood that was a golden cage in which others had planned to lock us up.

With a touch of indifference and a shrug of the shoulders in that so Cuban gesture that, translated into verbal language, means “Me? What do I care?” the new generation of young people is dismantling what is left of the Cuban system. It is doing this without heroic gestures, one could almost say with a certain reluctance and a touch of indifference. Nothing they say from the official podiums touches their hearts, or even instills fear.

Unlike those who came before, today’s Cubans under 25 don’t know about the ration book for manufactured products, where you could buy a single pair of pants or one shirt per year. They barely remember hearing a speech by Fidel Castro and haven’t had to accumulate ideological merits or brownie points at or work to be able to buy a home appliance.

Instead, they live on an island where the only valid thing is real money, which is achieved by doing the exact opposite of what my father once had to do to get a refrigerator, and where the black market has crept into all spheres of life.

Almost from childhood, these Cubans of the third millennium have been glued to a computer keyboard. Their parents bought their first computers and laptops in the illegal market. Their first kilobytes and videogames have come through the alternative distribution networks and represent the exact opposite of the ideology taught to them in school.

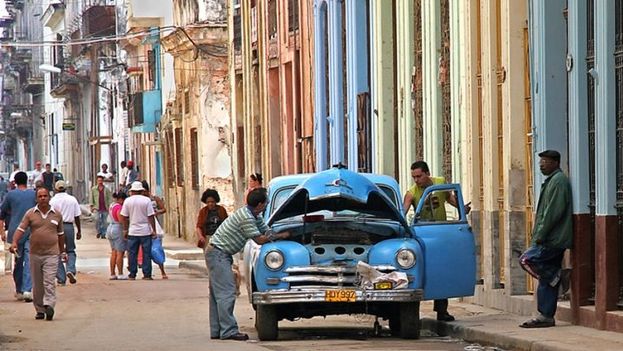

With haircuts inspired by Japanese manga, by figures from international show business or rebellion, today they populate our streets.

My son’s generation does not seek revolutions because they already know what they cause. They have learned to be suspicious by nature of Robin Hood style discourses that know how to steal from the rich and divide the spoils among the poor, but have never learned to generate wealth, to make a prosperous nation, one with opportunities like those once promised by that band of outlaws that came down from the mountains with their beards and olive green uniforms.

Today they have the appearance and dreams of any young German, English, Guatemalan. They look back with the necessary disdain and with a certain confidence that the future will not be as predicted in the science fiction books of the twentieth century, nor like that predicted by totalitarian ideologies. They believe it will be, at least, a more humane and pluralistic time, and a more free one.

When someone tells them that the Castro regime is here to stay and that Cuba will never return to its democratic path – imperfect and risky, like that of any nation – these Cubans living on the island today smile and remember those impetuous young people who drove the changes in the far off Soviet Union. Like them, they say to themselves, it doesn’t matter that the historic generation has the power, because we – fresh and skeptical – have the time.

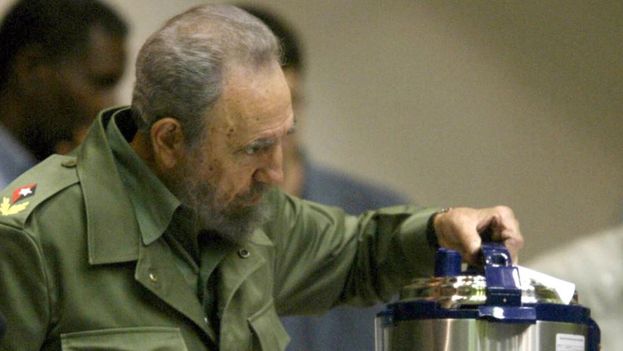

They grow up, go to the gym, listen to pirated music like anywhere else on the planet, make love, take selfies, try to share their lives on the web, and continue to live in a country where officialdom fears information. In short, they are twenty-somethings while Fidel Castro is in his nineties. They belong to the twenty-first century, but the old caudillo remains a prisoner of the twentieth.

These grandchildren of the generation of sacrifice and children of the generation of Utopia are the ones who, for the most part right now, feed the emigration that is crossing Central America. They suffer, die and are carried away in the hands of the coyotes while escaping the country that, by this time, should be the paradise once promised by their elders.

These young people today are the future. They will do it their way. Without listening to the advice of their parents. Who, under 30, follows the path traced by others? Especially when those who preceded them were so wrong? They are the grandchildren and children of a chimera. They come with the necessary pragmatism of forgetting and with the indulgent balm of forgiveness. They will live in a Cuba we never imagined, or knew how to achieve. A country, finally, with room for everyone.

_________________

Editor’s Note: Lecture given on October 6 by Yoani Sanchez in Juan Bautista Gutierrez Francisco auditorium at Marroquin University in Guatemala.

![]() 14ymedio, Yoani Sanchez, Havana, 8 November 2016 – On Tuesday a new era opens for the United States and for the rest of the nations on the planet, while for Cuba a period of great opportunities will end, one that the Plaza of the Revolution’s stubbornness did not use to its advantage.

14ymedio, Yoani Sanchez, Havana, 8 November 2016 – On Tuesday a new era opens for the United States and for the rest of the nations on the planet, while for Cuba a period of great opportunities will end, one that the Plaza of the Revolution’s stubbornness did not use to its advantage.