Peralta and her husband, José Antonio Rodríguez, hardly remember a time without hardships. “Our generation had to tighten our belts in the 70s, when we thought that everything would be better afterwards,” recalls this retired nurse who, together with her husband, receives about 30 CUC (Cuban convertible pesos, worth less than 30 dollars) from their monthly pensions. continue reading

“In those years it seemed that the ration book was something that would end soon,” recalls Peralta. Established in 1962, the rationed market has been one of the tools of what is officially called “the Cuban Revolution,” but which others prefer to call “Castroism” or, more popularly, “this thing.”

For 56 years, through this little booklet, food has been distributed at subsidized prices and in limited quantities. The State spends more than one billion Cuban pesos (CUP) per year in subsidies for these products, which it distributes every month and which are barely enough for ten days.

This distribution system has modified the Cuban diet, traditional recipes and even ways of speaking. In rationed bakeries “the bread” is sold, but when it is offered in unrationed stores, it loses the definite article and remains only “bread.”

For decades, the libreta, or ration book — from which, over the years, products have been subtracted — has been the favorite target of comedians, caused many family fights and caused numerous heart attacks or fainting outside the ration system’s bodegas. Three generations of Cubans do not know life without this little booklet with its gridded pages where, every month, a few pounds of sugar, salt, grains and some chicken are duly noted.

Several economic studies in recent years suggest that a salary of at least 1,200 CUP is needed to cover the basic needs of an individual in Cuba. With less than a quarter of that idyllic sum, Peralta and her husband gave up lunch years ago and at breakfast they just drink a tisane made from leaves collected in the backyard, along with a piece of bread.

No one can survive in good health if they eat only what is sold in the ration market. “If it weren’t for my daughter, who lives in Nevada, sending me a package with food and some money every month, we would be nothing but bones,” says the retireee. During the years of the Special Period, in the 90s, her husband was sick of polyneuritis, an illness caused by a lack of nutrients.

“It was at that moment that we touched bottom and since then we have been left with many manias around saving,” adds the husband. In the house, they reuse the cooking oil over and over again. “We even put it in through a strainer to remove the breadcrumbs and keep using it.” The eggs in the refrigerator have an initial, “G” or “J” written them depending on who their destined for.

“Each month they sell us ten eggs on the ration book, half at a subsidized price and the other at one peso each,” Peralta calculates. “But in recent years the supply has been very unstable and the only source of protein we have left is the chicken in the shopping (hard currency stores) or the pork that we can buy from time to time in the agricultural market,” he clarifies.

The hard currency stores are much better stocked but the relationship between their prices and wages is disproportionate. Their opening, more than two decades ago, was a concession made by Fidel Castro after the social explosion of August 1994, known as the Maleconazo.

“We had to be on the verge of starvation before they would allow these stores and also non-state agricultural markets,” Peralta recalls. At that time the Government also authorized foreign investment and, for the first time in decades, allowed the people to engage in private work, which was renamed with the euphemism cuentapropismo (’on one’s own account’, commonly translated as ’self-employment’).

For two years now, as Venezuela’s economic support to the island has languished, the shelves of the shopping — hard currency stores called by this English word — have had large empty spaces. “Before, the problem was that we had to get the money to pay for a bag of milk powder, but now you can have the convertible pesos and the milk does not appear,” laments Rosario, 34, the mother of two children ages nine and ten.

The rationed market establishes a quota of milk or yoghurt for infants but it is only provided until they are seven. “My children are forming their teeth and they need to consume dairy products,” explains Rosario. “My full monthly salary, about 590 Cuban pesos (about $23 USD), goes to buy milk at the shopping.”

The rest of the food is paid by the mother with the money she ’resolves’, a euphemism used to describe the process of acquiring informal additions, so common in the family economy. Jobs in the state sector are not measured by the salaries they pay but by access to products or raw materials that can be ’diverted’ and sold in informal networks.

“I work in the detergent and soap industry,” she says. “I have to take risks and take out a certain amount each week to support my family because otherwise it would be impossible.” Rosario considers herself one of those “few Cubans who do not have a family abroad” who has to “fight hard for every convertible peso.” Most of these profits are spent in the network of hard currency stores, the shopping.

In the Plaza de Carlos III in Havana, the largest shopping mall in the capital, a dozen people were wating this week for the supply of chicken to arrive at the butcher shop. Most of the frozen products that are marketed in the network of state premises come from abroad.

This year, the authorities calculate that they will import food worth 1.738 billion dollars, 66 billion more than in 2017. The low productivity in agriculture and livestock on the Island require bringing in everything from beef to fruit for the hotels.

Raúl Castro’s government took measures to support production on island farms, such as leasing idle state lands to farmers, but excessive state controls, restrictions against intermediaries and the imposition of prices caps continue to hold the sector back.

At the end of 2017, the average salary reached 740 CUP per month, a little more than 29 CUC (less than 30 dollars). However, the gradual increase in the average salary has not translated into a real improvement in living conditions.

For a professional, the goods bought in the rationed market and subsidized services such as electricity, water and gas consume a third of their monthly salary. However, at the prices in the unrationed markets, the other two-thirds is just enough to purchase five pounds of pork, a bottle of oil, a bag of milk powder, two soaps, a can of tomato sauce and a packet of flour — a month.

The general secretary of the only union allowed, the official Workers’ Confederation of Cuba (CTC), Ulises Guilarte de Nacimiento, had to acknowledge recently that wages on the island are “insufficient” to cover the needs of the worker, which causes “apathy,” “disinterest” and an a “significant migration of labor.”

Rosario, the illegal seller of soap and detergent, caters to several clients whose salaries are not enough to buy the product at the shopping and so they turn to the black market.

Among them is Pedro Luis, who was a promising editor at the Cuban Book Institute in the 80s. Back then, when his recommendations influenced the publication of stories and novels, his salary of 350 CUP allowed him to eat with variety, dress elegantly and decorate the house that he had inherited from his grandparents in good taste. They were the so-called “golden years” of the Revolution, in which the gigantic subsidies of the Soviet Union (some 5 billion dollars a year) artificially propped up the Cuban economy.

“We lived in an unreal world and with the fall of the Berlin Wall we had to come down to the true situation of the country,” says the pensioner. “Most of my friends who were living quite well back then are now selling newspapers so they can buy food or they have gone with their children to other countries.”

Nearly 80 years old, Pedro Luis is now a retiree who tries to survive with the 200 CUP (less than $8 USD) he receives as a pension. He had to sell two-thirds of his extensive library to eat and for the past five years he has rented half of his house to a family that treats him as an intruder.

Thanks to the good relations he maintained with the Catholic Church, the retiree has managed to be accepted, during the day, in a care home under the joint custody of the clergy and the State. During the hours that he spends there, he wanders through the corridors waiting for lunch and dinner.

“On Tuesday there was only rice and a boiled egg” he laments, but his face lights up when he remembers that “sometimes they give us a couple of sausages and on the best days we get soy ’ground meat’, although the quantities are very small.”

Pedro Luis is one of those Cubans who needs the little bread that is his daily due from the rationed market because he can not aspire to something of higher quality from the unrationed market. The last days of each month he gets up at dawn to stand in line at the bodega to buy the groceries in the ration book, a line he shares with those most dependent on that small basic market basket.

For years he has forgotten the taste of real beef or fish, products that are well above his financial means. A friend more solvent, with two emigrated children, invited him recently to eat shrimp and he was licking his lips for several hours.

Now the former editor plans to sell the last books he has left, just the most appreciated, then he will put a price on a pair of shirts and his last coat and will also offer some shoes. “With the money I make, I’ll be able to continue for a few months but after that I do not know what’s going to happen.”

________________

The 14ymedio team is committed to serious journalism that reflects the reality of deep Cuba. Thank you for joining us on this long road. We invite you to continue supporting us, but this time by becoming a member of 14ymedio. Together we can continue to transform journalism in Cuba.

The alliance of Venecuba with 14ymedio and the Venezuelan newspaper Tal Cual has supported this reporting.

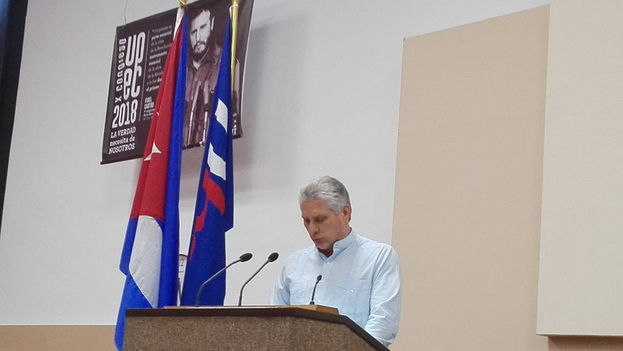

![]() 14ymedio, Reinaldo Escobar, Havana, July 10, 2018 — We now know that at its seventh plenary session the Communist Party Central Committee reviewed the draft of the new Cuban constitution. It was reported that the text of the document is now a fait accompli. In the coming days deputies to the National Assembly will approve what is still a draft. It will then be released for public comment after which the final draft will be submitted for a referendum.

14ymedio, Reinaldo Escobar, Havana, July 10, 2018 — We now know that at its seventh plenary session the Communist Party Central Committee reviewed the draft of the new Cuban constitution. It was reported that the text of the document is now a fait accompli. In the coming days deputies to the National Assembly will approve what is still a draft. It will then be released for public comment after which the final draft will be submitted for a referendum.