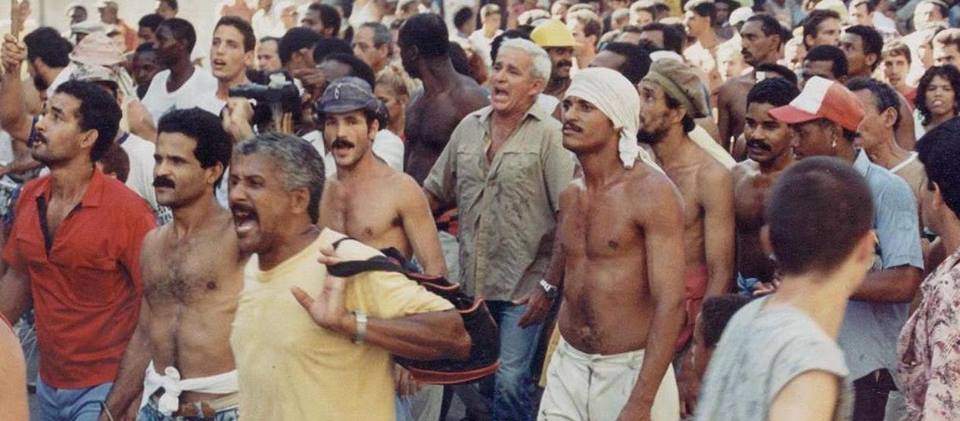

14ymedio, YOANI SÁNCHEZ, Havana, 5 August 2014 – We had run around together in our Cayo Hueso neighborhood. His family put up several cardboard boxes in vacant lot near Zanja Street, similar to those they’d had in Palmarito del Cauto. His last name was Maceo and something in his face recalled that Titan of so many battles, except that his principal and only skirmish would entail not a horse, but a flimsy raft. When the Maleconazo broke out he joined in the shouting and escaped when the arrests started. He didn’t want to go home because he knew the police were looking for him.

He left alone on a monstrosity made of two inflated truck tires and boards, tied together with ropes. His grandmother prepared water for him in a plastic tank and gave him a can of condensed milk she’d been saving for five years. It was one of those products from the USSR whose contents arrived on the island congealed, after the long boat ride. My generation grew up drinking this sugary lactose mixed with whatever came to hand in the street. So Maceo added the can to his scanty stores—more as an amulet than as food—and departed from San Lazaro cove.

He never arrived. His family waited and waited and waited. His parents searched the lists of those held at the Guantanamo Naval Base, but his name was never on them. They asked others who capsized near the coast and tried to leave again. No one knew of Maceo. They inquired at the morgues where they kept the remains of the dead who washed up on shore. In those bleak places they looked at everyone, but never saw their son. A young man told them that near the first shelf he had come across a single raft, floating in nothingness. “It was empty,” he told them, “it only had a piece of a sweater and a can of condensed milk.”

Editor’s note: Today is the 20th anniversary of “The Maleconazo.” You can read more about this uprising and the subsequent Rafter Crisis in previous posts: