The Castro brothers consolidated their power through purges that eliminated key figures of the Revolution, many of them born in the capital.

![]() 14ymedio, Rafael Bordao, Miami, November 12, 2025 — It is striking that, for the past 73 years, Cuba’s main heads of government have shared a common origin: a rural background. From Batista, Fidel, and Raúl, born in the province of Holguín, an agricultural region in eastern Cuba, to Miguel Díaz-Canel, also from a province outside the capital, political leadership has been marked by figures formed in environments far removed from Havana’s cosmopolitanism. This campesino root profoundly influenced their vision of the country, favoring a revolutionary narrative centered on the countryside, the fight against urban elitism, and the redistribution of wealth, although often with contradictory and catastrophic consequences.

14ymedio, Rafael Bordao, Miami, November 12, 2025 — It is striking that, for the past 73 years, Cuba’s main heads of government have shared a common origin: a rural background. From Batista, Fidel, and Raúl, born in the province of Holguín, an agricultural region in eastern Cuba, to Miguel Díaz-Canel, also from a province outside the capital, political leadership has been marked by figures formed in environments far removed from Havana’s cosmopolitanism. This campesino root profoundly influenced their vision of the country, favoring a revolutionary narrative centered on the countryside, the fight against urban elitism, and the redistribution of wealth, although often with contradictory and catastrophic consequences.

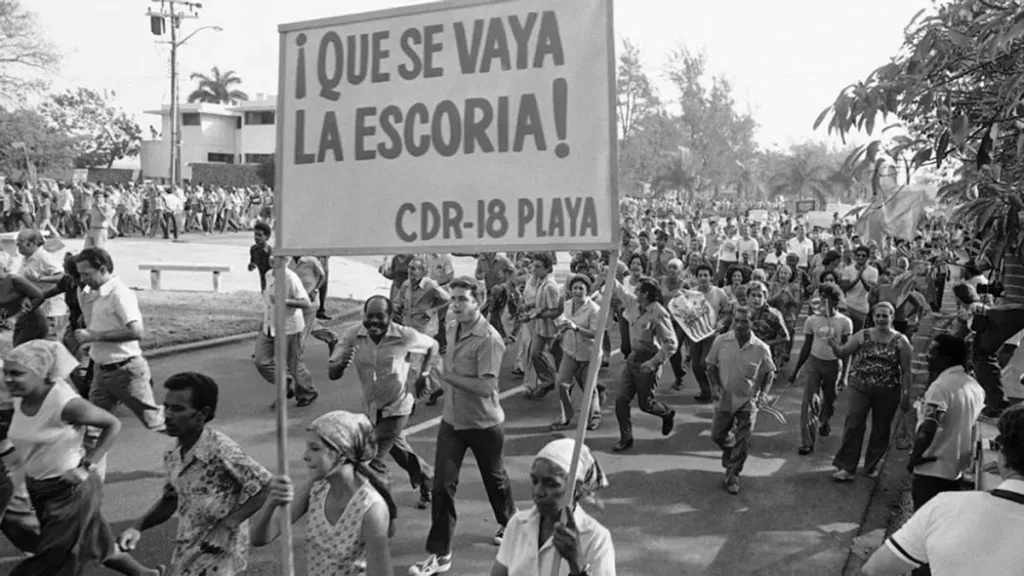

When Fidel Castro seized power in 1959, a considerable portion of Havana’s population—especially from the middle and upper classes—emigrated into exile, primarily to Florida. In their place, Havana was repopulated by campesinos brought from the interior of the country, many of whom were housed in the former mansions confiscated from the bourgeoisie. This forced relocation generated a culture shock: the new inhabitants, unfamiliar with the codes of urban life, felt uncomfortable in spaces they didn’t fully understand; some didn’t even know what a bidet was for. The revolution, by appropriating properties without compensation, unleashed a wave of resentment and social upheaval. The country, in its attempt to reinvent itself, saw its traditional structures dismantled, giving way to a chaos that, for many, was both a punishment and the consequence of a historical vendetta.

The history of the Castro regime is marked by a liturgy of silences and defenestrations

The Castro brothers consolidated their power through a series of political purges that systematically eliminated key figures of the Revolution, many of them Havana natives, such as Ricardo Alarcón de Quesada, who had the potential to succeed them. The history of the Castro regime is marked by a liturgy of silences and defenestrations. From the removal of President Manuel Urrutia in July 1959, the mysterious disappearance of Camilo Cienfuegos, and the arbitrary arrest of Commander Huber Matos, the continue reading

Over the decades, leaders such as Carlos Lage, Felipe Pérez Roque, and José Abrantes (all from Havana), and Carlos Aldana were removed from power without credible public explanations, victims of a system that punishes autonomy and popularity. Even Eusebio Leal Spengler, the cultured and revered historian of Havana, was quietly sidelined, and although he died—according to the authorities—of a painful illness, his Catholic faith and his cosmopolitan and cultural vision of the country not only contrasted with the military stubbornness of Castroism, but also distanced him from socialist dogma, which probably prevented him from rising to positions of greater influence.

These purges were not merely a response to political errors, but rather to a logic of structural distrust. Power in Cuba is not shared: it is inherited, monitored, and purified. The fall of each figure (the most recent being that of economist Alejandro Gil Fernández) is accompanied by a eulogy that sounds like an epitaph, and the ensuing silence is as eloquent as the accusation. In this context, the Revolution has become a closed space, where absolute loyalty to the Castro leadership is the only guarantee of permanence.

____________

COLLABORATE WITH OUR WORK: The 14ymedio team is committed to practicing serious journalism that reflects Cuba’s reality in all its depth. Thank you for joining us on this long journey. We invite you to continue supporting us by becoming a member of 14ymedio now. Together we can continue transforming journalism in Cuba.