![]() 14ymedio, Pedro Acosta, Havana, 21 January 2021 — Five years ago, Edelmira Rodríguez laid the first brick in her house. It was the beginning of a dream, of building her house with her own efforts, which at times turns into a nightmare. The shortages and the lack of liquidity mean that, to this day, the roof has not even been installed.

14ymedio, Pedro Acosta, Havana, 21 January 2021 — Five years ago, Edelmira Rodríguez laid the first brick in her house. It was the beginning of a dream, of building her house with her own efforts, which at times turns into a nightmare. The shortages and the lack of liquidity mean that, to this day, the roof has not even been installed.

Rodríguez, an employee of the Ministry of Labor and a resident of Havana, was enthusiastic about the push the authorities gave a few years ago to the construction of houses by the interested parties. After decades of strict controls on the sector, permits have become more flexible in the last decade for those who wish to start this kind of work.

Given the lack of State resources, more than half of the homes built in Cuba between January and October 2020 were built by individuals, according to the Minister of Construction, René Mesa Villafaña. During that period, 40,215 houses were completed in Cuba, of which 23,429 (over 58%) were built privately. continue reading

During that period, 40,215 houses were completed in Cuba, of which 23,429 (over 58%) were built privately.

But behind those numbers there are thousands of stories of difficulties and moments of hopelessness like the ones Edelmira Rodríguez is living through today. “The land they gave me is only seven meters long by six meters wide and that forces me to build a two-story house,” she explains to 14ymedio.

A construction of more than one story requires that the lower structures be able to support the weight of the second story. This translates into having greater quantities of steel, cement and other materials, but these resources are not always available, or of the required quality.

“I started five years ago and have not even been able to install the first-floor ceiling. Since before the pandemic began, the materials were nowhere to be found, and the price of cement in the black market is prohibitive, and let’s not even mention the rebar”, Rodríguez laments.

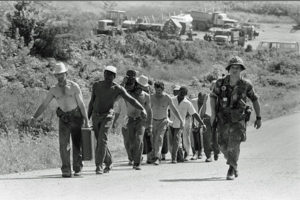

Those shortages also encourage the theft of building materials. Avoiding losing aggregate and bricks becomes such a nightmare that it often forces families to permanently camp on the construction site.

“Not only do you have to monitor whether they are taking cement or not in the wheelbarrow, but also keep your eyes open so that they do not steal in one night what has cost you months to obtain”, says a young man who is making repairs to his home in Calzada del Cerro. In the front porch of the house, whose roof collapsed a few years ago, sandbags and stone dust are piled up.

“My father watches at night and I do so during the day, because we cannot lose any of this material. Here, in this neighborhood, there are many people who are trying to repair or build their own little houses, but cement is only available at the foreign currency stores”, explains the young man. “Rather than because of self-effort, this is due to self-strain, because nothing is guaranteed”.

The improvised builders complain that banks grant very small loan amounts, ranging between 20,000 and 80,000 pesos, but currently in the informal market one bag of cement exceeds 500.

The improvised builders complain that banks grant very small loan amounts, ranging between 20,000 and 80,000 pesos, but currently in the informal market one bag of cement exceeds 500.

In recent years, this material has become a rare “gray gold”, sought by all those who want to repair a kitchen, modernize a bathroom or touch up a facade. For two years, the product has barely appeared in the stores that take payment in Cuban pesos and has been rationed in State construction yards for victims of natural disasters.

The shortage of the product was aggravated by a tornado that hit Havana in January 2019. With thousands of houses affected, the State guaranteed a 50% discount off the cost of construction materials for people with houses damaged by the disaster in the neighborhoods of Luyanó, Regla, Guanabacoa and Santos Suárez.

The monetary unification and the rise in many prices of products and services since last January first, the has had a negative effect on those who dream of finishing their own home. Some, like Tomasa Correa and her husband, have had to move into the house while still waiting to be able to buy what is left to finish construction.

“We still have to install the glass on the windows and front doors on both floors,” says Correa. “Public Health gave us the go-ahead and for a few months we have been living in the house but we have the biggest problem with the money we owe,” she acknowledges. Debts in excess of 60,000 pesos have been accumulating and now the couple does not know how they are going to repay that sum.

“We have a food stand offering vegetables and fruits located in a privileged area and over two hundred people pass through there in any given day. In addition, attached to the stall, we sell soft drinks, juices and condiments, but sales have been declining for months in a tailspin, due to lack of products”, Correa details.

However, Correa feels lucky to have been able to finish her home, in a country that needs around a million homes. Others have barely advanced beyond the foundations or some walls of what will be their future home. As is the case with Gerardo Mena, who has been with his family for 15 years in a shelter for victims of the disaster after the collapse of their building.

“Economically, we are not doing badly, but in Cuba, it is not enough to have money to solve things. Three years ago, I bought a piece of land in Monaco [Cuba] from the State and began to build a house for the family.”

“Under these conditions, my wife and I had two daughters because time went by and we couldn’t keep waiting to become parents until we owned a house,” Mena told 14ymedio. “Economically, we are not doing badly, but in Cuba, it is not enough to have money to solve things. Three years ago, I bought a piece of land in Monaco [Cuba] from the State and began to build a house for the family.”

A brother who emigrated helps him with part of the resources he needs to buy materials, but even his solvency has not materialized in advancing with the construction. “In these three years I have not been able to go beyond raising the walls and building the supports on the first floor,” Mena laments.

But even those walls that have yet to be plastered are an unattainable illusion for Eduardo Portales, a Havana native who has been trying for a long time to buy a piece of land on Vento Street from the State. About four years ago there was a small store that offered its products, selling its goods from a metal container placed on the site. Now, the metal box is rotting in the open while officials of the Physical Planning Institute and those of Tiendas Caribe play hot potato avoiding the responsibility of removing it.

Until the container is removed, the land purchase process cannot be finalized. But when the site is finally liberated, Portales will still have the long and tortuous path of starting to build with his own effort.

Translated by Norma Whiting

COLLABORATE WITH OUR WORK: The 14ymedio team is committed to practicing serious journalism that reflects Cuba’s reality in all its depth. Thank you for joining us on this long journey. We invite you to continue supporting us by becoming a member of 14ymedio now. Together we can continue transforming journalism in Cuba.