![]() 14ymedio, Clara Riveros, Miami, 25 February 2024 — “In Cuba we didn’t have air conditioning. Flies and cockroaches are everywhere. My grandfather had a hobby of rolling up the Granma newspaper to catch flies, we competed, I was a child, that entertained me.”

14ymedio, Clara Riveros, Miami, 25 February 2024 — “In Cuba we didn’t have air conditioning. Flies and cockroaches are everywhere. My grandfather had a hobby of rolling up the Granma newspaper to catch flies, we competed, I was a child, that entertained me.”

The Havana artist Fabián Peña recently won a scholarship from the Cintas de Miami Foundation, an institution that for several decades has supported and promoted Cuban artists and creatives or those of Cuban descent in various artistic branches.

He won the $20,000 visual arts scholarship and these resources are above all a premium in terms of time. The artist will be able to dedicate the time needed to create his proposal and which he plans to complete towards the end of the year. “There will be 20 monochrome portraits of 20 negative characters from the 20th century. The list includes dictators, Stalin, Castro, Hitler, serial killers, terrorists and characters who have defined the history of the 20th century in a negative sense, but they will be represented when they were “children, between 9 and 12 years old. Their faces will be displayed on a canvas, like the paintings, but they will be paintings with cockroaches. They are not exactly paintings, they are collages of cockroaches, of the mosaic type, displayed in a wall installation,” he said in conversation with 14ymedio .

In 20 years working with cockroaches and flies, Peña has been perfecting his technique with these peculiar materials which he speaks about with propriety and expertise.

In 20 years working with cockroaches and flies, Peña has been perfecting his technique with these peculiar materials which he speaks about with propriety and expertise. And what we usually discard and reject as terrifying, repulsive and unpleasant, has been reinvented and resignified by the artist. “It is a very artisanal work and, still, without a defined name,” he says regarding the project on which he is working.

“Cockroaches are our undesirable pets, like flies. Cockroaches are in the darkness, they have a particular light, they are very curious, prehistoric. They create an ethical/aesthetic conflict. They have very particular tones, colors, they are a mysterious universe and with a lot of potential, talking about these as material and color. Here I use them for that red tone that is reminiscent of blood, like the characters that are going to be represented.” continue reading

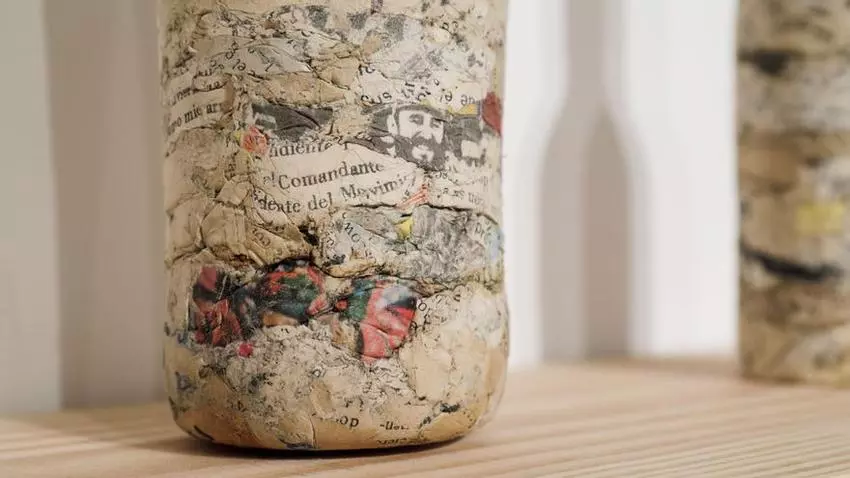

Peña’s other major project this 2024, for the Puerto Rico Biennial, to be held this coming April 18, is his proposal Por ti yo muero [For You I Die], which outlines an almost religious meaning. The concept of paper in his work suggests that, being a carrier of ideas and ideologies, it becomes a fossil. The Marxist-Leninist ideas and aesthetic references put on paper that were present in the artist’s training process and, now, that same paper transformed in his hands acquires a new meaning, that of obituary material as an implacable metaphor of an outdated ideology already used not only for indoctrination and instruction, but also for destruction.

The artistic commitment for the Puerto Rico Biennial evokes the process of his Embotellados [Bottled] series, exhibited in 2016. “On this occasion the bottles contain 10 fundamental books, including fundamentalist ones, carriers of outdated ideologies and approaches that may well lead to destruction, both on a political and religious level, but there is also a place here for some literary pieces that have managed to earn a place in History.”

Fabian Peña was born in Havana, in 1976. Graduating from the Higher Institute of Art, his artistically inclined training spanned 12 years. A year after graduating, in 2004, he left Cuba for the first time, an exit with no return. “I was born in El Vedado but I grew up in El Cerro, which is a very sui generis place. My neighborhood was not a marginal neighborhood as such, but it was very close. Very poor, but the people, the neighbors, were very cool at that time. That part is greatly missed. I had the privilege of having artist friends close to me, for example Lázaro Saavedra, who was a friend and teacher of mine and lived almost next door to my parents’ house, and Roberto Favelo, Adrián Soca. I felt very motivated by having artists and people from another generation related to art and artistic creation nearby. We would talk about projects and we would end up at a party. All this towards the end of the 90s.”

“We had the office there, that’s what we called it, we were the Enema Collective. We did performances like La Morcilla: 13 of us took blood and made a blood sausage. We also did an intervention at Lázaro’s house, who was in the United States for a scholarship and extended his stay, so we paid him a tribute in absentia because we didn’t know what had happened to him. That place is very symbolic of that time for its energy and as a meeting point.”

That was a fundamental stage, very productive. Later it was not like that, as an immigrant the priority is to earn a living

“Did you have the option of professional development in Cuba?” he was asked. “In a short time of professional life in Cuba we developed many projects and initiatives. There was hunger, difficulties, censorship, but we wanted to take on the world. My work, our work, gained visibility, generated interest and that gave us opportunities that perhaps others did not have so early, because there were many curators who were interested in what we did. Everyone went to the Havana Biennial and we were there. That was a fundamental stage, very productive. Afterwards it was not like that, as an immigrant the priority is to earn a living. Being an immigrant made me see the reality of how it works.”

“The regime has played the cultural card and its bet has helped make the Cuban cultural scene relevant throughout the world. Wasn’t your art intended to transgress the system? Why did your work have greater possibilities than those of other artists?” 14ymedio asked the artist.

“We spoke in metaphorical terms about things that were happening and that allows for many interpretations. If it was done in a very obvious way they would censor it. We did a performance, for example, cleaning floors of cultural institutions in Cuba, with floor rags, and this would wear them out and they would take on shapes. In the so-called Special Period, in some places those rages were cooked like steaks and given to people, deceiving them, of course.”

“After cleaning the floors with those rags, we made banners with that material; we used about 50 rags for each space. At that time we were immersed in Eastern philosophy, we made a kind of abstract painting with those rags, we wrote with shoe ink in Japanese the explanation of the work: “With these rags the Plaza of the Revolution in Cuba was cleaned.” We gave solemnity to the banners, it looked like something symbolic, sacred, it was a way of taking dirt to a sublime state. This work was even taken to the Guadalajara International Book Fair (FIL) in 2002, which had Cuba as the guest of honor. The work, they say, generated strangeness because people were used to seeing another staging, another concept of Cuban art, not to seeing the ‘grime’ of cultural institutions, presented in such a solemn way.” Solemnizing the filth? “It worked very well in that context.”

Peña has been busy imagining, producing and creating, guided by intuition. “I like that the result of the work exceeds what I initially thought.” But he has not taken care to keep enough records for posterity to attest to the genius of these performances and creations. When presenting this situation to him, he notes that the initial work was poorly documented, much was lost in Cuba or the photographs that were taken were very poor and with devices that do not reflect the quality of the work in all its expression. Some of what exists was documented by Cuban art historian and curator, professor at the Art Institute of Chicago, Rachel Weiss. But in the United States, Peña has not recovered the memories of all of his work either.

His art left Cuba before him, considering that the installation of the banners was taken to Guadalajara in 2002. A year later, Peña went to Mérida. “Many curators from the United States went to Cuba and bought works. We had some money, not to get rich, but to live with what was necessary and continue producing and living off of art.”

And why did he leave? “Because not having had serious problems with the regime does not mean that we were not going to have them. Or that later it would become impossible to leave. There was an opportunity and we had to take it. Furthermore, the situation between Mexico and Cuba had deteriorated at the level political and diplomatic between Fidel Castro and presidents Ernesto Zedillo and Vicente Fox. We had many friends and contacts in Mexico, that is, the entire platform to stay for a while, but we decided to embark on the adventure to the United States. On that journey a lot of the work was also lost, because they were installations and performances that you will never do again. Mexico was a rewarding and successful experience, artistically speaking, the first time I left Cuba.

He left without saying goodbye. He didn’t tell anyone, not even his parents. His mother’s tears were premonitory of the imminent reality. More than five years passed before Peña saw her again.

“The Cuban artist from Cuba is sexier than from Miami. It is more interesting for the foreigner what the person there says”

The escape was planned from Cuba, always in secret. He left his sister as a teenager and found her in the fall of 2011, dancing ballet at the Guggenheim in New York. She is still in Cuba.

What is it like to be an immigrant? “It is in some way like living a double life. Being an artist. Producing and creating. But in parallel it has also been learning other trades to survive. I have been a social worker, I have worked on golf courses, in stores, in offices, but never “have I given up on art, never have I given up on creating. My work in itself takes a long time to think about, create, produce. It is a very long process.”

After a brief period in Houston, Peña was already working with a gallery here in Miami. In addition to doing performances at Florida International University and in different places, he always interacts with the public. “Miami was the target because we had people here, acquaintances, art historians, curators and colleagues from the cultural and artistic world that we had met in Cuba. People who had noticed, by the way, since the 90s, that contemporary art in Cuba was taking place despite the lack of information and news from the outside world and that it had nothing that detracted from what artists were doing in the 90s in New York,” he notes, while observing the works of Rubén Torres Llorca and José Bedia and touring the Coral Gables Museum to which he is professionally involved part-time. And he points out that it is striking that the regime had not accused the exponents of Cuban contemporary art of “ideological diversionism,” as was usual.

Also from the outside there has been or was the perception that “the Cuban artist from Cuba is sexier than one from Miami. It is more interesting for the foreigner what the person who is there says.” He has seen it there and has lived it here.

In 2007, at Art Basel, five minutes after the fair that was taking place at the Miami Beach Convention Center opened, his work was sold. The buyer, Lance Armstrong, had paid $21,000, according to local media. It doesn’t seem like a bad start on American soil.

Peña continued doing something he had started in Cuba: collages with crushed flies and also cockroaches. With flies, one of his favorite creations is Frozen Flight from 2008, a flag made with hundreds of fly wings that formed a unique fabric like lace or semi-transparent fabric. The work hanging from the ceiling maintained a certain natural rotating movement, which intensified with the proximity of the public. It is a work of a fragile and at the same time resiliant nature.

In 2017 he released Frozen Capital, made with compressed paper of the famous work of Karl Marx, covered in flies and glass. Similar to a popsicle covered in chocolate and nuts. “In 2017 I did the last exhibition with flies. I presented it here at the David Castillo Gallery, Frozen Capital, it represents Marx’s Frozen Capital. I compressed the pages and made a popsicle, an ice cream, the cover was not chocolate, but flies and the nuts were the glass of the bottles with which I compressed Marx’s book.”

____________

COLLABORATE WITH OUR WORK: The 14ymedio team is committed to practicing serious journalism that reflects Cuba’s reality in all its depth. Thank you for joining us on this long journey. We invite you to continue supporting us by becoming a member of 14ymedio now. Together we can continue transforming journalism in Cuba.