Photo: Karen Miranda

Photo: Karen Miranda

The sergeants collect the empty trays, so well cleaned by the tongues of the detainees they don’t need to be washed.

The sound of the last door being shut leaves a silence that makes them feel more trapped, and the air, scarce and hot, suffocates them.

No detainee would even dare to raise their voice to avoid being taken to the punishment cell for indiscipline. The sergeants walk slowly, stopping to spy through the doors and listen to what the prisoners say when the apathy and despair of seclusion provokes a feverish state of anxiety that spills out into idle talk, and later they denounce them to the higher-ups.

When the silence feels eternal, some sadistic mechanism stops the night, making it last longer than usual; and there comes a whisper, a word grinding at the metal doors, sliding on the floor like a glass of water; and the detainees are frightened because they know well the voices of each sergeants, the steps, the way they let their boots fall when they walk, how they clear their throats and even how they snore. So, from their cells, they are all intrigued because they can’t decipher whose voice escapes like a lament. This time it is not someone who dreams and calls out for a loved one or shouts the name of an officer telling him to stay away, now someone shouts from a cell, every word pronounced forcefully; at first you can’t hear what he’s saying, then you understand something like, “I’m hungry.”

The sergeants quickly walk past the cells, searching, like dogs with rabies, for where the voice is coming from; they open the slot, tell him to shut up, but the detainee talks, and through the orifice of the door the words escape with more clarity, forgive me, sergeant, but I don’t know how to bear hunger, I can’t stand it, a thousand pardons, but I have always been a man with a good appetite; the guards continue advising him it is better to remain silent, that if he continues it will go very badly for him; the prisoner begins to plead, and the plea becomes tears. They warn him that later they won’t be able to do anything when he wants to stop, now is the time; but the detainee cries like a baby and asks forgiveness, he was never a man who caused problems, I never have been, please, understand me.

The sound of the padlock is heard, and then of the bolt being violently opened, then the screech of the hinges. The man’s panic grows, his weeping increases while the menacing voices of the sergeants question him; he begs them not to hit him; and the guards tell him then shut up and they’ll leave and there won’t be any problems; they insist that he understand they are giving him more chances than usual, but the detainee claims that they don’t understand him, the problem is that he can’t stand the hunger, it’s something that’s not in me, I don’t know how to control it.

We hear a few blows, and then he cries. The sergeants ask him if he is finally going to shut up, and the prisoner in the midst of his uncontrollable crying explains that even a piece of stale bread is enough, a tiny scrap of leftovers, a piece of sweet potato. The guards realize that not even the blows will shut him up and decide to take him to the punishment cell, what they call “the hammock.” His weeping turns into screams of panic, not the hammock, please, not there. And the sergeants force themselves on him to immobilize him to be able to move him. The detainee twists his body, curls up like spring so he can burst out and escape the hands of jailers, until he can’t move any more and they drag him in front of the other cells. He keeps crying and apologizing, he doesn’t want them to see him as an antisocial, he’s a good man, but with a big appetite, this is his only crime. Not the hammock, I’m afraid, he says. They take off his clothes, as the punishment requires, throw him in the cell and close it; but the soldiers know they haven’t done much, the detainee keeps asking for food because he is a man with a good appetite, he’s convinced that this excuse is enough to make them understand.

The sergeants open the cell, they warn him if he keeps acting up it’s going to make them furious. But nothing shuts him up, he asks for food over and over. One of them enters, desperate, and hits him over and over until he realizes he won’t shut up as long as he’s conscious. Another soldier brings handcuffs for his hands and feet and some bandages to tape his mouth. They struggle with him a while until the voice of the detainee can no longer be heard. Then they slam the door and from the footsteps of the sergeants and the way they let their boots fall, the detainees conclude that they are tired. The silence returns, a silence that had been forgotten for a few minutes.

At dawn, they open the punishment cell. Nobody has been able to sleep thinking of the man in the “hammock,” on the damp floor bathed by the drops of water that inevitably fall from the ceiling and crash against his body; they know it’s unbearable to spend an entire day there.

When they take the bandage off his mouth he’s still crying, now with less strength, but you can still hear his voice: I’m hungry, please, I’m a man with a good appetite.

Translated by Raul G.

August 29, 2010

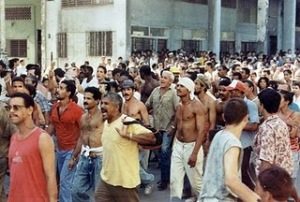

WHEN, IN AUGUST OF 1994, the generation of the children whom no one wants was preparing their rafts along the Cuban coast, you could hear the cries of the mothers who searched for their children over several nights, and the sea, cloudy, let out a long roar, breaking against the reefs.

WHEN, IN AUGUST OF 1994, the generation of the children whom no one wants was preparing their rafts along the Cuban coast, you could hear the cries of the mothers who searched for their children over several nights, and the sea, cloudy, let out a long roar, breaking against the reefs.

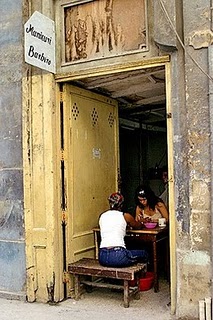

THE GIRL WHO LIVES above my apartment is named Pilar and comes from an ancient Catholic family. She’s had a relationship with her boyfriend for three years. In these thirty-six months they’ve been excited many times. Alberto lives with his parents and grandparents. And for her, it’s the same. It has been very difficult to satisfy their erotic instincts.

THE GIRL WHO LIVES above my apartment is named Pilar and comes from an ancient Catholic family. She’s had a relationship with her boyfriend for three years. In these thirty-six months they’ve been excited many times. Alberto lives with his parents and grandparents. And for her, it’s the same. It has been very difficult to satisfy their erotic instincts. Photo: Alejandro Azcuy

Photo: Alejandro Azcuy

RECENTLY I HAVE BEEN HOPING I might read my blog for the first time. Some friends have seen it and described it to me, and I feel the same pleasure as when they speak to me about my children. They suggested that I buy a card that would let me enter cyberspace from the services in hotels. Two and a half months after starting the site, I still haven’t been able to see it. I’m anxious to read it, feel it, smell it. I imagine its design would give me a feeling of tenderness. Recently an old man asked me if I was sure if civilization existed outside this island.

RECENTLY I HAVE BEEN HOPING I might read my blog for the first time. Some friends have seen it and described it to me, and I feel the same pleasure as when they speak to me about my children. They suggested that I buy a card that would let me enter cyberspace from the services in hotels. Two and a half months after starting the site, I still haven’t been able to see it. I’m anxious to read it, feel it, smell it. I imagine its design would give me a feeling of tenderness. Recently an old man asked me if I was sure if civilization existed outside this island.

Photo: Karen Miranda

Photo: Karen Miranda OUTSIDE OF EVERY imaginable world, is the extreme awareness of reality, you live in cell twelve feet by six feet, usually with four inmates, sometimes sixteen who have to stand up, and when it comes time to sleep they fall slowly, like fainting, like sugar canes thrown on top of one another, creating a deformed mass, you couldn’t guess which extremity belongs to whom.

OUTSIDE OF EVERY imaginable world, is the extreme awareness of reality, you live in cell twelve feet by six feet, usually with four inmates, sometimes sixteen who have to stand up, and when it comes time to sleep they fall slowly, like fainting, like sugar canes thrown on top of one another, creating a deformed mass, you couldn’t guess which extremity belongs to whom. On Tuesday night, June 29, in the city of Pinar del Rio, we delivered as part of the jury, the prizes in the contest of the independent magazine Convivencia (Coexistence).

On Tuesday night, June 29, in the city of Pinar del Rio, we delivered as part of the jury, the prizes in the contest of the independent magazine Convivencia (Coexistence). Ángel Santiesteban Havana 1966. Graduate of Dirección de Cine, resides in Havana, Cuba.

Ángel Santiesteban Havana 1966. Graduate of Dirección de Cine, resides in Havana, Cuba.