Miriam Celaya, Cubanet, Havana, 22 January 2016 – The imminent arrival in the US of thousands of Cubans stranded in Costa Rica has, once again, unleashed the debate whether the Cuban Adjustment Act its right or not, its original foundations, and opinions on whether Cubans who are exiting today should be considered political immigrants and, because of it, deserve to benefit from that law.

The subject stimulates strong feelings, as is always the case among Cubans, clouding objectivity and making it difficult to demarcate between legal matters, political interests, personal resentments and the purely human issue, which is ultimately what motivates all exodus, beyond particular circumstances marked by politics and economics.

Positions are usually polarized, unqualified and exclusive: they either favor the infinite arrival of Cubans to the US – particularly to Miami, the offshore capital of “all Cubans” – and the ‘irreversibility’ of the Cuban Adjustment Act, as a sort of divine right inherent to those born within the Cuban Archipelago’s 110,000 square kilometers, or they advocate the repeal of the law and limiting or cutting off aid to all those who arrive.

And, since anything goes when it’s time to taking advantage of the situation, the new migration crisis has also been seized by some Cuban-American politicians to stoke the embers against the move towards the warming of diplomatic relations with the Cuban government initiated by the White House, creating uncertainty about the possible disappearance of the Cuban Adjustment Act, and with it, the privileges Cuban immigrants to the US have enjoyed.

Unfortunately, this approach overlaps the real cause of the growing exodus out of Cuba: asphyxia, decay, and condemnation to eternal poverty under an obsolete and failed sociopolitical system thrust on them almost 60 years ago. With or without the Cuban Adjustment Act, Cubans will continue to emigrate, either to the US or to any other destination, which is evident in the existence of communities of Cuban emigrants in countries where there are no Adjustment Act Laws from which they might benefit.

Ergo, the controversial Law – which, by the way, the Cuban authorities did not even mention during the honeymoon days with the Soviet Union – is an undeniable part of the problem, but not the most important one, so that its repeal will not constitute the solution to the unstoppable flow of people from Cuba.

In fact, we can categorically state that if the legislation should disappear, Cubans will not give up on their desire to enter US territory, and, once in the US, they would survive in illegality, just as millions of “undocumented” Latin-American immigrants have done. Haven’t we been trained for decades here in Cuba, where everything good seems to be prohibited, to survive in illegality in a thousand different ways?

The “legitimate” children of the Cuban Adjustment Act

It is difficult to objectively review a legal tool that has protected so many fellow Cubans. But when we talk about the Cuban Adjustment Act itself, we inevitably recall the causes and circumstances that gave rise to it.

Enacted in 1966, the Act gave legal status to a large number of Cubans who had been forced to flee Cuba, many of whom had been affected by revolutionary laws or had serious accusations hanging over them, either for real or alleged collaboration with Batista or other crimes considered ‘against’ the triumphant Castro revolution.

We must recall that, back then, the firing squad was still the usual sentence applied to “traitors” by the guerrilla gang that took power in 1959. Punishable categories could equally include being members or supporters of the former dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista, and being participants in the revolutionary struggle that opposed Fidel Castro’s turn to communism, some of whom returned to armed struggle as a form of rebellion and were defeated.

Cuban exiles of the ‘60s were mainly families of the upper and middle classes of the bourgeoisie who had been economically affected by nationalizations and other “revolutionary” measures, and whose interests were incompatible with the political line taken by the Cuban government.

And it must be noted that when they left Cuba they were stripped of all their rights by the Cuban revolutionary laws. From a legal point of view, returning to Cuba was not an option for them. Thus, the Cuban Adjustment Act was created to resolve the legal limbo in which these early Cubans were living, when, seven years into the Castro regime, all indications were that their return to Cuba would be more protracted than previously anticipated.

The rest of the story is well known. A law arising for the benefit of Cuban political exiles in the heat of the Cold War evolved into a standard when it extended to every Cuban who sets foot in the US, even though most of them arriving today do not consider themselves as politically persecuted by the Castro dictatorship.

“I’m going there to do my own thing”

None of the phases of the long Communist experiment in Cuba have been without migration. With its peaks and valleys, the outflow was an important sign of the history of the Cuban nation in the last 57 years under the same government and the same political system.

Current circumstances, however, are not the same as those that existed as the backdrop of the migration of the 1960’s, the spectacular Rafter Crisis of 1994 or the colossal Mariel Boatlift of 1980, when the abuse of repudiation rallies, humiliation, and beatings promoted by the government, organized by the Cuban Communist Party (PCC) and the mass organizations are etched forever in the memories of both those who left and those who stayed.

Cubans who fled in the early years of the Revolution suffered a complete break with what was their way of life in Cuba and were stripped of property and rights as nationals. They endured the condemnation of those who are exiled without the possibility of returning to their homeland for decades, by which time many of them or their family members who stayed behind had died, without even being able to say goodbye. They were the direct victims of the political system that some of them had even helped bring to power. What is clear is that in the last four or five years the reality has changed, and so has the perception that the current emigrés have about their own situation.

Cubans who emigrate today not only define themselves mainly as having economic motives, but under Cuba’s migration reform of 2013 they preserve both the rights to their property and the right to enter and leave Cuba within 24 months, plus at least the minimum rights that are enshrined in the Cuban Constitution.

A great part of them have declared that their intention to emigrate was so they could improve their material living conditions and help their family in Cuba – that is precisely the same aspirations of millions of Latin-Americans – and they even repeat that everlasting, all-knowing phrase, so often heard around here: “I don’t care about politics, I’m going there to do my own thing.”

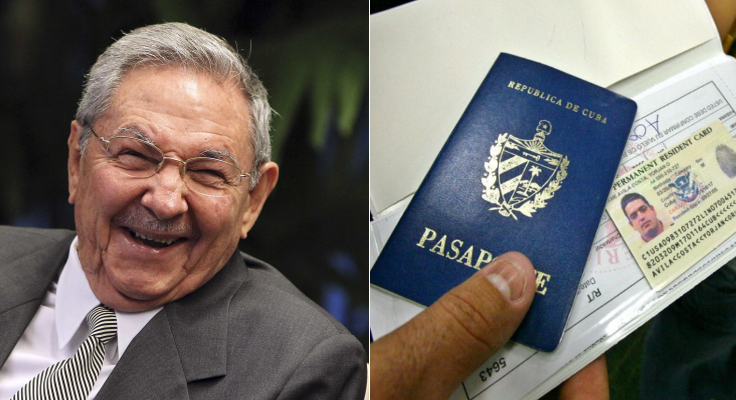

And, indeed, once they have obtained their legal residence (the famous “green card”), they begin to travel to Cuba before the expiration of the two-year grace period granted to them by the Cuban government to preserve their rights as natives of the dilapidated island hacienda. “Fears” of reprisals from the Castro regime that they were experiencing when applying under the Cuban Adjustment Act abruptly and magically disappear, once they qualify.

This is a triple benefit: for Cuban emigrants because they get favored twice, with the Cuban Adjustment Act and with Raul’s immigration reform, and for the Cuban government, because migration has become one of the few sources guaranteeing steady net income and constant foreign currency inflows.

After that, privileges to fast legal access to work, a Social Security number, food stamps and other benefits received because of their alleged condition as “persecuted,” in reality becomes a kind of legal scam of the public treasury to which taxpayers contribute, especially Americans who have nothing to do with the Cuban drama. This is the essential argument used by those who believe that the time has come to – at least – review the Adjustment Act and modify it so that it can accommodate only those who can reasonably be regarded as “political refugees.”

But the biggest trap of the Adjustment Act does not lie exactly in tending to reinforce the intangible (and false) Cuban exceptionalism, or in its current ambiguity or discretion that some future modification might grant it, but – just like happens with the embargo – its real inconvenience resides in making a foreign law responsible for the solution of problems that are clearly national in their nature.

Once again, the quest for solutions to the eternal Cuban crisis is placed on the shoulders of legislators and other foreign politicians, a reality that is indicative of the pernicious infancy of a country whose children are incapable of seeing themselves as protagonists of their own destinies and thus, with a change in the rules of the game in their own country, opt to escape the miserable Castro paternalism in order to benefit from the generous kindness of US paternalism. Cubans, let’s stop going around in circles; the problem is not the Adjustment Act or the clique of politicians here, there, or yonder, but in ourselves. It’s that simple.