![]() 14ymedio, Reinaldo Escobar, Havana, 25 September 2016 – If there is something it is difficult to disagree with the Cuban government about, it is the permanent defense of the people’s right to decide the economic, political and social system that suits them. This principle is put forward in every international forum attended by official representatives from the island, and is shared by the majority of civilized nations.

14ymedio, Reinaldo Escobar, Havana, 25 September 2016 – If there is something it is difficult to disagree with the Cuban government about, it is the permanent defense of the people’s right to decide the economic, political and social system that suits them. This principle is put forward in every international forum attended by official representatives from the island, and is shared by the majority of civilized nations.

In parallel, above all within Cuba, there is an intense campaign to fight any intention to change the existing regime in the country. Clearly, if the intentions to change “the existing regime” come from another nation and are contrary to the legitimate interests of the people, resistance to change is absolutely valid.

The question is whether that sacred right of the people “to decide” includes the option to “change” the system, regardless of whether the proposed changes coincide partly or completely, with some external proposal.

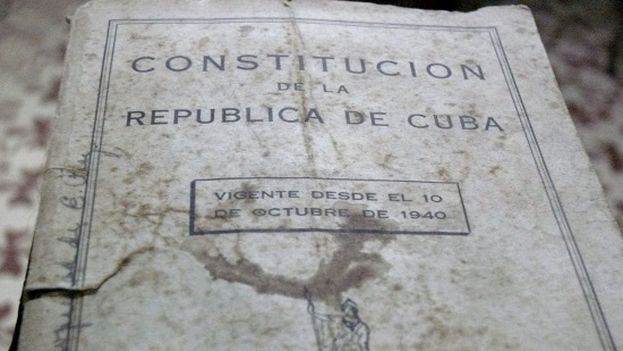

The first historical example in the case of Cuba was the change that occurred in the early twentieth century when we replaced the colonial regime, which subjected the people’s will to the will of the Spanish metropolis, to a new system in which the island became a Nation, established as a Republic. That change, imperfect, incomplete, truncated, responded on the one had to the popular will and on the other hand to the interests of a foreign nation, the United States of America.

The second example was the regime change proclaimed in April of 1961 when Cuba became “the first socialist country in the Western Hemisphere.” That substantial modification, which had not appeared clearly indicated on the revolutionary program that overthrew the brief dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista, was only submitted to citizen consultation, through a vote, 15 years later, when there was no private property left in Cuba, no entity of civil society, no independent press media and only one permitted political party.

The millions of Cubans who, with their secret and direct vote, approved the 1976 Constitution, where the new social regime was enshrined, which also coincided with the interests of a foreign nation, the Soviet Union, to support the presence of socialism “under the noses of imperialism.” The USSR did not hesitate to offer everything: food, arms, troops, oil, credits and whatever diplomatic and political support needed.

At the turn of the years to socialism in Cuba, the Republic passed away. Although no one had baptized it pseudo-socialism or mediated socialism, it has been necessary to add an “our,” at the risk of committing the revisionists’ sin.

That system approved by popular vote 40 years ago does not greatly resemble what is described today in successive guidelines issued by the only legally permitted party, but the changes introduced have only been discussed with the party membership and other representatives of certain previously chosen institutions.

Among the possible commonalities between the Party Guidelines and the interests of foreign nations, say China or the countries of the ALBA bloc, could be a sterile exercise of political speculation, especially in a globalized world where almost no country enjoys total freedom to dictate laws while turning its back on the interests of the rest of the planet.

The right of Cubans to maintain the regime is only legitimate if their right to change it is also recognized. The desire for uniqueness, the obsessive vocation of not resembling the other, of not coinciding with the interests of anyone, would be a difficult caprice to satisfy and an impossible one to pay.

Addressing regime change now, introducing changes to the regime or leaving everything as it is, requires a prior exchange of opinions and a subsequent approval. Only if there is freedom to debate and guarantees of a free vote, would it respect the sacrosanct right of the Cuban people to decide which system they wants to live under.